How can we promote innovation and respond to challenges?

Overview

Now that we’ve explored the basics of change management and fostering change, we need to talk about the elephant in the room – how we can actually promote innovation and respond to challenges as they arise. In the last few years, education as a sector has faced many challenges due to a number of factors, so in this chapter, we’ll look at what challenges may arise, as well as how to encourage innovation.

Learning Outcomes

- Understand the nature of innovation and how we may foster it

- Understand how current events may affect edtech (e.g., data breaches, health crises, advancement in tech)

- Understand how to work within the limitations of our work culture to support change and technology adoption

- Understand forthcoming and emerging trends in edtech / online learning

Why is this important?

When tackling leadership challenges and opportunities in educational settings, and when implementing new technologies in the same context, we must always have a good understanding of how things may be impacted by forces we can’t control, while also considering how workplace culture may foster real innovation

Guiding Questions

As you’re reading through these materials, please consider the following questions, and take notes to ensure you understand their answers as you go.

- How innovative is your workplace? What is the culture around it, and is that culture changing?

- How can the primary users of a new technology be involved in the change management process?

- What events (planned or unplanned) may impact the success of a technology implementation or innovation project?

- What constraints do you identify with your technology rollout or implementation, and what can be done to respond to them?

- What trends in pedagogy or technology may play a role in your technology rollout?

Key Readings

For this chapter, you’re encouraged to explore more literature on your own context to explore innovation,

Harris, A., & Jones, M. (2020). COVID 19–school leadership in disruptive times. School Leadership & Management, 40(4), 243-247.

Bower, M., Henderson, M., Slade, C., Southgate, E., Gulson, K., & Lodge, J. (2025). What generative Artificial Intelligence priorities and challenges do senior Australian educational policy makers identify (and why)? The Australian Educational Researcher, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-025-00801-z

Laufer, M., Leiser, A., Deacon, B., Perrin de Brichambaut, P., Fecher, B., Kobsda, C., & Hesse, F. (2021). Digital higher education: a divider or bridge builder? Leadership perspectives on edtech in a COVID-19 reality. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 18(1), 1-17.

Tabata, L. N., & Johnsrud, L. K. (2008). The impact of faculty attitudes toward technology, distance education, and innovation. Research in higher education, 49(7), 625-646.

Tong, K. P., & Trinidad, S. G. (2005). Conditions and constraints of sustainable innovative pedagogical practices using technology, 9 (3). IEJLL: International Electronic Journal for Leadership in Learning.

Fostering Innovation

Innovation is “the act or process of introducing new ideas, devices, or methods” (Meriam-Webster). Innovation requires work, stretching individuals and groups and organisations beyond their comfort zones and to step outside the established ways of doing business. For many this can be a challenging enterprise, and in educational technology, this is no different.

Consider this question: Is innovation different than change, or are they same? There is no write or wrong answer to this, but it might be that change is something that is mandated, whereas innovation is something that is optional and therefore a little more challenging to work with.

Innovation can occur on many levels within education, from the individual teacher trying a new technology and practice, to a cohort of teachers within a domain / subject area doing the same, to an entire school, state or nation adopting new technologies and practices associated with them. For this reason, innovation is not something that is easily wrangled, but something that is better understood, so leaders can encourage and foster it within existing workplace cultures.

Rogers (2003) outlines a few characteristics of innovation that can help us to guide our own thoughts on leading it.

- Relative Advantage – how an idea is thought of when compared to existing ways of working / doing

- Compatibility – how compatible the innovation is with existing perceptions of practice or working

- Complexity – how easy to use or understand is the changed practice / technology?

- Trialability – how much a new idea can be experimented / trialled / played with within a limited time frame

- Observability – how much the results of the innovative idea can be observable by others.

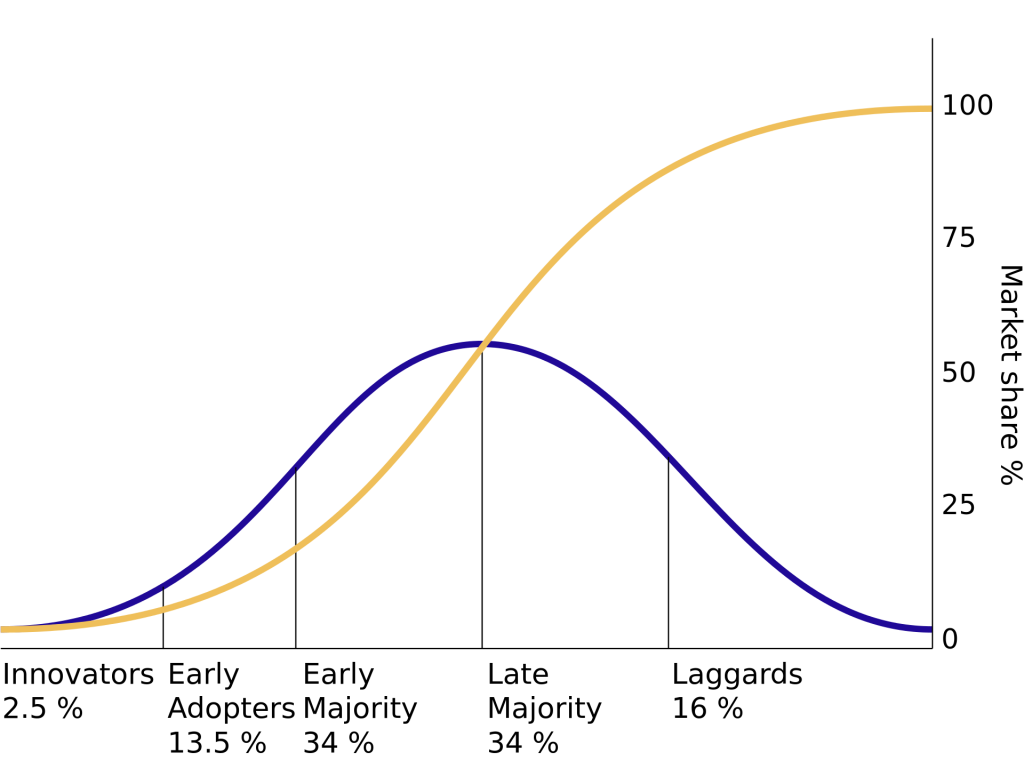

He also outlined how adopters of innovative practices may engage in the adoption over time.

The diffusion of innovations according to Rogers (1962). With successive groups of consumers adopting the new technology (shown in blue), its market share (yellow) will eventually reach the saturation level.

Rewards and Incentives

Tabata and Johnsrun (2008) outline the many factors that may play a role in how instructors may perceive changes in their practice. While not the newest research article, many of the points they hit on and describe are still true to today, covering things we’ve already explored in this book, including:

- Re-thinking Training and Development

- Learning Design and Technical Support

- Quality of the Learning Experience

- Expectations for Participation

- Workload and compensation

That last point is an important one, in that it ties directly into the motivation of our peers to work on and implement change. Essentially this is all about ‘buy-in’, or how much individuals are on board with changes that are hoping to implemented. When instructors / teachers are working full time and expected to keep up with their field, engage in other professional learning opportunities unrelated to technology, it can be sometimes be challenging to be excited about any changes that they may not consider integral and will take considerable time and energy. This is where incentives come in.

When working to lead any innovative project, motivation plays a key factor and depending on the culture of the workplace. In any culture there are always going to early-adopters or ‘rock stars’. These individuals are always game to try new things and to experiment, with the support of leadership and support staff. For those who are either on the fence, apathetic or resistant to proposed changes motivating ‘carrots’ may provide the right push. Examples could simply be workload allocation changes to allow those engaging in this work to have the time to do so. It may also come in the form of monetary rewards for engaging in this work, such as mini-grants or equipment procurement. There are many other strategies that can differ greatly based on context, but the key with these strategies is that they seek to alleviate the concerns that instructors and teachers may have with their limited time, and provides an incentive (a carrot not a stick) to engage in innovative practices when they may not be fully on board.

Grassroots or Top-down

Another consideration is where innovation and new technologies projects are led from, including who is on the project’s leadership team and who is involved in decisions-making. This can come from the following areas:

- Grassroots – people on the ground doing the work, such as teachers, technology support staff and others

- Top-down – Administrative or leadership staff

- A mixture of the two – this usually involves academic leadership staff working on the same team as those who will be working with the technology very day, ideally with equal footing in terms of how the project is run and decision-making aspects.

Grassroots innovations can come in many forms, ranging from teachers and technology staff simply trying new things on a very small to medium scale, using a trial and error approach. These innovations can then diffuse to colleagues and spread amongst the staff without any clear plan or project definition – it’s just people trying stuff.

Top-down may essentially look like a mandated change coming ‘from the top’ where the perception is that no one has a choice in the matter, and the reasons for change may not be communicated in the best way possible. As Sidorkin (2017) notes, “Top-down reform as a change strategy has shown very little efficacy and may actually counteract the authentic innovations” (p.136). Lisewski (2004) outlines a case study wherein they suggest that successful innovation and change is dependent on an understanding of the relationship between levels in a hierarchy in an institution and engaging interested parties at all levels can lead to successful change. In other words, top-down alone, won’t work and may feel mandated, so it’s important to involve employees at all levels of the hierarchy to ensure that the appropriate input and motivation to conduct the change is there. With that being said, we should also consider the opposite, that purely grassroots change may not go anywhere without involvement and support from those at the top.

Mixing the top-down and grassroots approaches is now incredibly common as it takes into considerations the needs and wants of those who will be expected to do the important innovation work, while also being led by parties responsible and accountable for any changes that occurr.

With this in mind, as educational technology leaders, its important to consider how we approach the change itself, including who we involve in the process and how we can capitalise on all experience and expertise around us.

Startup Culture and Education

While mostly present in business education, the concept of Startup Culture has been working its way into educational settings (in small pockets), but can provide a useful way to think about innovation and how it can be nurtured. Williamson (2018) discusses various schools set up by philanthropists in Silicon Valley in San Fransisco, California with the aim of providing unique and innovative educational experiences to students.

The video below, outlines how Australian universities are building this culture into how they work (again mainly in business education) to foster and provide exemplars of how young leaders and entrepreneurs can start their own business.

While we may not all be leaders or teachers in business, startup culture can also provide us some example of different ways to work, including, but not limited to:

- Informal meetups to talk about a project, whether it be sharing ideas or to raise concerns

- Hack-a-thons or Sprints – short events designed to encourage people to work together to create something, either in competition or collaboration

- Resource Access can allow innovators to get their hands on things that they may not normally be able to, which would be fantastic for educational technology projects.

- Seed funding to start projects

Unfortunately, in the private sector, there have been many examples of where a Startup Culture can lead to a toxic work environment, perhaps due to the instructor nature, fast paced work environment and constant change. In educational settings Startup Culture can take a very different form, in that the institution can simply provide the opportunities for innovation (as listed above) and generally disrupt organisational norms to foster innovation.

In many educational institutions, there already basic aspects of this culture around, including grants, exploration spaces / maker spaces, and communities of practice. Leadership in educational technology can think about the best approach to implementing their project or promoting innovation and embed these practices into existing ones (such as communication and training) or add new ones as they see fit. After all, changes in practices that don’t involve technology may be able to support changes in the use of technology.

Anticipating and Responding to Changes

Starting in 2020, a global health crisis changed education in ways that we could never have anticipated. Many of the worlds educational institutions had to rapidly ‘pivot’ to teaching and operating in a purely online setting in order to protect the health of their populations. While the decisions made by national leaders is not within the scope of this chapter, this global event provided us with insights into what changes we could make, how these changes could be made, and how fast. The impact on teachers, learners, pedagogy, technology, leadership and other factors were thrust into an ‘innovate to survive’ modality, where if we couldn’t adapt, we risk either shutting down, or not being able to do our jobs. The choice was clear, and changes were made and innovations adopted out of necessity.

As simple Google Scholar search for ‘COVID Education‘ is a good place to start exploring all the research that has come out of the COVID-19 pandemic with regards to how it has impacted the education and training sector, both with regards to technological innovations as well as pedagogical and leadership / support initiatives.

While the COVID-19 pandemic was only one such unanticipated event that could impact our efforts to innovate and lead educational technology initiatives, there are many others, including weather events, data breaches, hacks, workforce changes, regulatory and compliance changes, among others.

It’s important then, to consider the changes and innovations we are hoping to implement, and what we can proactively consider in terms of what could affect the success of our project. Planning for any and all eventualities may not be realistic, but to build in contingencies for primary anticipated events, as well as a few peripheral ones might be a good idea.

Constraints and Opportunities

When confronted with changes that are outside of our control these circumstances usually present us with constraints as well as opportunities. Constraints are typically things that will limit our ability to do what we want to do how we’ve always done it. Opportunities are usually in the form of things we can do make our situation better. I’m sure as we all experienced in the years after 2020, we experienced many situations where we couldn’t conduct business as usual, and to make changes to adapt. For most of us, this was frustrating, challenging and draining, but the silver lining of this experience was that we could do things differently. Many of us were afforded more flexible working arrangements, a more flexibly schedule to complete our work and more opportunities to try new things. On the technology side, many educational technologies rapidly expanded in use gained new features and became part of cultural lexicon (eg. Zoom is now a verb), while other technologies that didn’t respond to the times were left to fade into the background and reduce their market share.

Constraints are good for innovation.

Independent of health crises or weather events, working within the limitations of what our culture and infrastructure allow, and getting creative so all users / learners can benefit is also something we need to consider.

Depending on where our projects and innovative initiatives are situated there will be differing levels of freedom to act upon what we personally think is the right course of action. There may be government or regulatory standards we need to conform to, national or state-level curriculum to work with, and when working with technology, infrastructure, budgets and existing systems we need to integrate with.

Tong and Trinidad (2015) outline many factors that may play into the success of technology innovation in Hong Kong. Along with issues discussed in previous chapters, their model includes factors including teacher and student readiness, technical infrastructure, the nature of leadership and others. This will differ greatly from institution to institution, but the more we know about the constrains we face, the more we’ll be able to confront them, and this is where it’s important to weave in elements of evaluation and research into our projects.

One may consider ‘competition’ a constraint as well. If we think about exploring what other similar organisations, schools or universities are doing with relation to our own work (e.g., like a market survey) we can find out where our technology implementation sits in terms of other parties. Are we behind or ahead? Are we using similar or the same technologies, or is no one using the technology we’re planning on using? By considering these questions we can better understand the landscape, whether or not this is a constraint is up to interpretation, but it can provide meaningful information to help us guide our decision-making.

By exploring the nature of the constraints we face, we’ll be better able to respond to them (endemic or unanticipated) as well as plan for the future.

Generative AI

One innovation and trend that is on many leaders’ minds is that of Generative AI (or genAI for short). These tools, including ChatGPT, Google Gemini, Microsoft Bing and Copilot, and many others allow for quick and precise generation of text-based content, as well as image and even video. The question of whether lesson planning, assessment design or feedback should be done by humans is now a valid question, with a few leaders in the education community advocating for outsourcing teaching to these chatbots. While this is an extreme position to take, there are my tasks that these tools are capable of that may support human work, including learning content generation, data analysis and assessment feedback. As these technologies are evolving quickly, its important for educational leaders to be aware of the challenges and opportunities they represent. For more on this, check out the article above by Bower, et al. (2025).

Keeping up with the Trends

Change is inevitable, and the technologies we use today may or may not be the same technologies we use a year from now. With this in mind, it’s important to consider the trends in technology as well as the pedagogies that support them. As technology should never be used for technology’s sake, having a good understanding of the trends in both pedagogy and technology can make us better leaders.

Every year, Educause publishes the Horizon Report, an in depth publication on the trends that we’ll be seeing more of in the upcoming year in teaching and learning.

As discussed in a previous chapter, the idea of longevity is an important one to consider, because the changes that we wish to implement, and the technologies we wish to roll out, will have a lifespan, so it’s important that we keep tabs on the trends so that our projects and rollouts don’t come too early, too late, or interfere with other projects. For example, let’s say we’re considering implementing a tool that relies heavily on the use of a specific Learning Management System (LMS), but the LMS’s contract is up next year. It may be that the original tool may not integrate well with another LMS, so it might be prudent to wait to ensure that all technologies work well with each other.

Feel free to explore the chapters below from Emerging Pedagogies and Practices in Learning Technology for more on specific tools and technologies, and the research behind them.

Key Take-Aways

- Fostering innovation usually can’t be done by an educational technology leader alone, but in collaboration with others

- Practices endemic in Startup Culture may provide a way to break the cycle of stagnating innovation

- Things may happen beyond our control, so when planning a technology implementation, it’s important to plan for these events.

- Technology is always changing, so we need to be mindful of what’s coming down the line and how it might affect our existing strategies and projects.

Revisit Guiding Questions

Think about your own learning context or workplace and think about how you could work with others to foster innovation. What practices might be used to disrupt and expand upon existing practices that may be stifling innovation? What contingencies should be put in place to ensure that technology implementations go smoothly and aren’t derailed or delayed by unforeseen events? What emerging trends in pedagogy and technology may affect your implementation, and how could you amend your implementation to ensure a longer life?

Conclusion / Next Steps

As this is the last chapter in this book, readers are encouraged to learn as much as they can about their own workplace or learning context. Exploring issues around evaluation, research and other players in the sector (e.g., other schools, universities, etc.) can help to ground your technology implementation and provide a baselines for ensuring its success.

References

Lisewski, B. (2004). Implementing a learning technology strategy: top–down strategy meets bottom–up culture. ALT-J, 12(2), 175-188.

Rogers, E. M. (2003). Diffusion of innovations. New York: Free Press.

Smirnov, I. (2017). Identifying factors associated with the survival and success of grassroots educational innovations. In Reforms and innovation in education (pp. 85-98). Springer, Cham.

Sidorkin, A. M. (2017). Human capital and innovations in education. In Reforms and Innovation in Education (pp. 127-139). Springer, Cham.

Williamson, B. (2018). Silicon startup schools: Technocracy, algorithmic imaginaries and venture philanthropy in corporate education reform. Critical studies in education, 59(2), 218-236.

Further Reading

Horizon Report 2021: Teaching and Learning Edition. Retrieved from https://library.educause.edu/resources/2021/4/2021-educause-horizon-report-teaching-and-learning-edition

Sidorkin, A. M., & Warford, M. K. (2017). Reforms and innovation in education. Springer.

Did this chapter help you learn?

No one has voted on this resource yet.