What is Learning Experience Design (LxD)?

Overview

In this chapter, we’ll be exploring different ways of engaging in Designing for Learning, including the terminology used in this work (it’s a bit confusing) along with major models used to perform this work in a more systematic manner.

Outcomes

After working through this chapter, you’ll be able to:

- Understand basics of LxD terminology and its purpose

- Differentiate between different models of LxD

- Understand how your lessons and integration of technology can be systematically designed

- Identify how LxD can support your work

Why is this important?

Different educational systems and organisations use different models as their foundation of work. If you’re developing self-paced training for the corporate sector, designing a learning experience for polytechnic or military settings, there might be different ways of doing it at each. If you work in a science department at a high school or archeology department at a university they may do things differently, still. The truth is, many workplaces that engage in this work may not have an established model at all, they may just work with their SMEs (Subject Matter Experts) in the best way that works. Having an awareness of more systematic ways of designing learning experiences is really important though, so you can plan your projects before you start to work on and develop them.

Guiding Questions

As you’re reading through these materials, please consider the following questions, and take notes to ensure you understand their answers as you go.

- How do you go about designing learning experiences yourself? Do you have a basis for how you do it, or is it just ‘by feel’ or using common sense?

- Have you encountered these terms before? Which of the terms in this chapter do you gravitate towards?

- Have you worked within a Instructional of Learning Design model before? How did you choose it?

Key Readings

Tawfik, A. A., Gatewood, J., Gish-Lieberman, J. J., & Hampton, A. J. (2021). Toward a Definition of Learning Experience Design. Technology, Knowledge and Learning, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10758-020-09482-2

Terminology

Not going to lie – terminology in this space is a bit confusing, and there are a lot of overlapping and converging terms. In a nutshell, Instructional Design was the standard for many years, now you’ll see many people with job titles like Learning Designer or Learning Experience Designer.

A useful activity to get a feel for these terms IRL (in the real world) is to go on different job sites and just search for these terms. (hint: ‘educational developer’ is another related job title that may overlap with these terms)

Instructional Design

Dr. Bullen does a great job here of describing the basics of Instructional Design, espeically with regards to the non-linear nature of the work we do. Historically Instructional Design has been all about what the instructor does, and thus, was more of an ‘instructor-centred’ approach. The video above, simply describes how that mindset has changed as many instructional designers still exist with that job title, their job has now evolved into more of a learning designer, while retaining the old term.

Learning Design

The next term in this evolution is all about the ‘Learning’. While it’s true that many educators still may think ‘textbook’ first in terms of their approach to designing instruction, the practices outlined in this chapter were developed when Learner-centered design was still not in the mainstream vernacular. Learning Design, therefore, is simply an updated term for Instructional Design, one the places more emphasis on what the learner is doing as opposed to the instructor.

Note that Learning design can be a process as well as a ‘thing’. Based on work by Agostinho, Bennett and Lockyer over the years (2006; 2016;2018), Learning design can also take the form of documentation of pedagogical intention and learner experience, meaning the culmination of the process of Learning Design is a Learning Design.

Designing for Learning

Now, the argument is often made that one can never ‘Design Learning’. Learning is a complex undertaking and experience that no educator could ever presume to design, given that individual differences between learners and the ways in which they learn are almost as unique as a fingerprint, so in some circles you may hear the phrase “Designing FOR Learning”. This phrasing, while not a job title, is just a way of considering how the work that we do is meant to facilitate learning in our students, as opposed to designing their individual learning processes.

Learning Engineering

This is a relatively new term, that leverage more technically advanced systems for personalised learning using AI (artificial Intelligence), ML (Machine Learning), LA (Learning Analytics) and Educational Data mining. The idea here is that learning experiences should be designed based on evidence from research on how people learn, with and without technology), while also adapting to learner needs on the fly by leveraging responsive educational software can actually take data in collects on the students that engage with it and supporting student learning needs as they progress. At the time of the writing of this chapter, this term is not so heavily used, but it is something to be aware of. Some educators may feel that this term is a little ‘cold’ or ‘robotic’, reducing human learning experiences to that of a cog in a machine, however with the interest in Learning Analytics and Learning Science related to the same, you may see this term more in the future.

Learning Experience Design

An emerging job title and way of thinking about this work, and one that addresses some of the issues that arise from previous terms is to think about students engaging in learning experiences. While we cannot design learning itself, we CAN design learning experiences, so this term has arisen in the last few years and you’ll see many job advertisements with this title.

The concept of LxD (Learning Experience Design) is actually rooted in the Design field. In design, there is a field called UX (User Experience) Design, and this accounts for how users (customers, learners, etc.) interact with products and systems, especially taking into account their affective experiences as well. As learning is not all about reading journal articles, writing essays and taking exams, engaging in LxD work allows us to think of the entire experience, including aspects related emotional, sociocultural, historical, diversity, technological and many other issues. LxD also overlaps somewhat with another field of design called Interaction Design (or IxD), which focuses on how users interact with systems – how they are designed, what users do with them and the steps they take to accomplish a task.

While this is a new term, there is still some overlap in terms of what many in the field understand it to mean. Check out the video below – based on this institution’s outline of what LxD is, does it seem more akin to instructional design or learning design? (note the mentioning of delivery of content as a means to support instructors)

Considering all these factors, most of this is common sense, but we can design learning experiences that account for who our students are, what affective experiences we want them to have while learning as well as the specific design, layout and navigation of the technologies we ask them to use.

Understanding the complexity of Learning Experience Design – Matthew Schmidt

The Rabbit Hole 🐇

If you want to go down a rabbit hole about this topic, feel free to explore the Wikipedia entry for Instructional Design. If you’d like to learn more about advancement in this area, feel free to have a look at What is the Future of Learning Experience Design? including a brief discussion of Human Centred Learning Design.

Models of Design

Models of Instructional / Learning / Educational design can guide the work involved in creating great learning experiences. Many instructional and learning designers use the ADDIE model, which includes the basic aspects of Backwards Design.

Backwards Design

Backwards design, while still technically an instructor-centered approach, was first outlined by Tyler in 1949. In this model, instructors first think about what they would like to achieve in their teaching, then they identify acceptable evidence for ensuring these objectives are met, then they plan instruction to ensure that learners are able to provide this evidence.

Backward Design is now around 70 years old, and its contemporaries form the modern basis of instructional design, starting not with content, with learner outcomes or objectives. By taking this approach, instruction can be targeted towards measurable knowledge, skills and abilities that learners will achieve, instead of what they will read or how many lectures they attend.

Identify Desired Results

In this stage, the instructor looks to their aims for the course and how the course fits into the degree, program or stream (the curriculum. The instructor then captures what they hope their students will achieve in terms of concepts, ideas and themes in terms of whey they want to students to know, understand or do.

Determine Acceptable Evidence

The instructor then thinks about what they would consider acceptable evidence for meeting the above results, and how they may go about collecting this evidence. This forms the basis of what types of assessment tasks are given to learners and how these can be taken together or independently to provide this evidence.

Plan Activities & Instruction

Lastly, the instructor considers what knowledge, and learning activities may contribute to supporting students towards providing the above evidence. This includes using specific teaching strategies, the selection of learning materials and activities that may foster further understanding of the topic and related concepts.

ADDIE

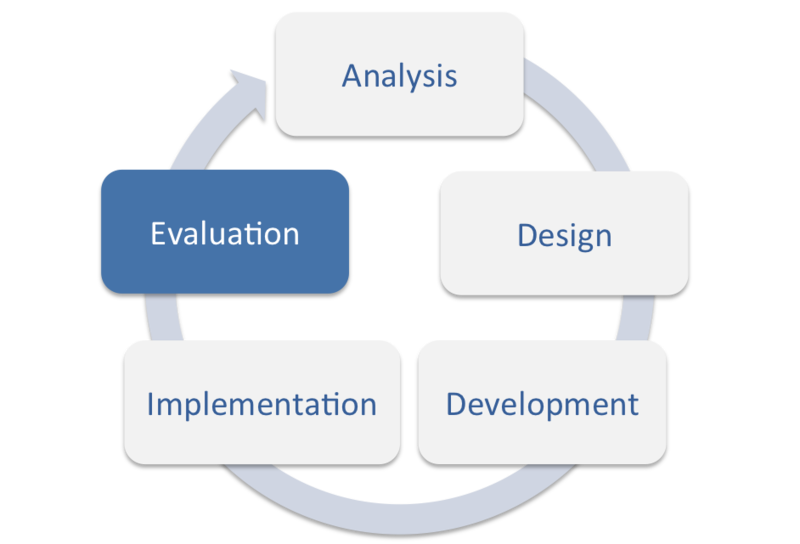

ADDIE is a cyclical model which takes includes a start-to-finish, practice-based approach to the development of courses, from a needs analysis to evaluating the effectiveness of the learning design from the perspective of the learners.

Analyse This phase can conduct an analysis in different ways. First you can look at previous iterations of a learning experience and revisit what worked and what didn’t, from both a teaching and learning perspective. Depending on the context, you can also look at the needs of the learners – are they actually learning what they are supposed to? How do we know? For many educational contexts, analysis also means working with external parties in the private sector, in standards agencies, and other organisations to ensure that students will learn what they have to. What we learn from this phase will inform the rest of our project.

Design This is where the majority of the work will take place, including revisiting learning outcomes for the class and units, ensuring alignment of formative and summative assessments, embedding learning activities and content, and choosing appropriate technologies to support each step along the way. This is usually done ‘offline’ as part of the planning phase (planning = designing in this model) so that we can be sure everything we’ve brainstormed and though of works.

Develop Usually initiated as the Design phase comes to a close (or close to it), development involves building the learning experience within a chosen learning platform, integrating any supporting technologies and creating any custom learning materials.

Implement The implementation of a learning experience means that it is taught. By the end of the Development phase, the your project should be ready to go, and the teaching and learning process moves forward. During this phase you’ll probably learn a few things about what worked and what didn’t, hence the E in the next phase.

Evaluate Evaluation can contain two steps. First, learner feedback is gathered to inform future changes needed for the next iteration of the project, which is preferred over using subjective experiences of an instructor – thoughts from the instructor are always useful, but we should be mindful that they may be biased. Additionally, an evaluation of the project’s development itself can also be conducted. This will both inform teaching practice, while at the same time helping those who worked on the project understand how the process went. Note that this process evaluation isn’t a part of the original framework of ADDIE, but is becoming more common in practice.

In this diagram we can see that evaluation is actually placed at the centre of this work, which changes the cyclical and almost linear way of approaching this work in the previous diagram – in this way of working, evaluation is embedded into every stage of the model. Which way of working do you think is the best?

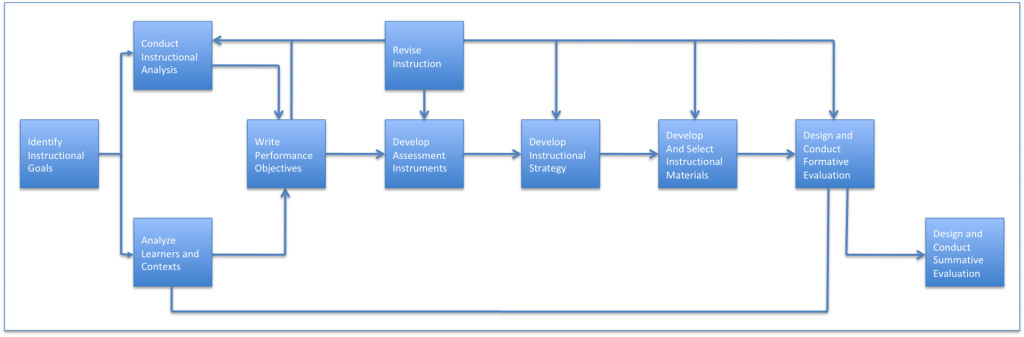

Dick & Carey’s Instructional Systems Approach

In Dick and Carey’s model, you can see its very similar to ADDIE, however the revision and evaluation and the analyse phases happen in a more non-linear fashion, with instructional strategies, learning materials selection and evaluation being constantly revised. This is one aspect of many learning design models that may be lacking, given that many educators’ design work makes up a small fraction of their other work, they cannot constantly engage in the design of their learning experiences, so many of the models may read as if when the design work done, it’s simply ‘done and dusted’, and will perhaps be revisited later, but not for a while. This is not the intention, however, as almost all of these models infer the constant revisioning of learning experiences based on feedback and evaluation.

RASE

RASE is a pedagogical model, first designed for science educators and adopted to a variety of other contexts. It was developed in 2013 by Churchill, King, and Fox to transform how instructors think about the relationships between learning materials, learning activities and assessments, asserting that content and resources are not enough for full achievement of learning objectives.

Resources can take the form of anything students will use to engage in the learning process including content, such as lectures, videos, readings; and materials and tools, such as objects they may use in class, software or even paper templates used in the classroom.

Activities are anything the learner does to help them understand and make connections between theory and practice and is essentially the situation in which learning happens. These characteristics in their most effective form are both:

- Learner-centred – Focused on what learners will do, as opposed to what they’ll remember; learners may produce artefacts that demonstrate their progress ; learners interact with resources; teachers participate in.

- Authentic – replicate professional practice, including scenarios that involve competencies, not just knowledge.

Support involves providing a scaffolded experience to learners, helping them in gaining new competencies and practicing mastery of those skills. Support should also anticipate the needs of learners, and this can take the form of the creation of resources to assist in their learning or clarification of complex topics, or building activities that ensure learners support each other either through in class or online discussions or even in the shared creation of a glossary or other resource.

Evaluation sometimes referred to Quality Assurance (QA) processes and reflection on the actual design of learning experiences on the part of the instructor, but for RASE, Evaluation refers to learner evaluation, including their own self reflection on the completion of tasks, what they learned, the feedback the instructor provides during the course of activities and assessment, all with the goal of allowing students to improve upon their work, and grow in their mastery of practice.

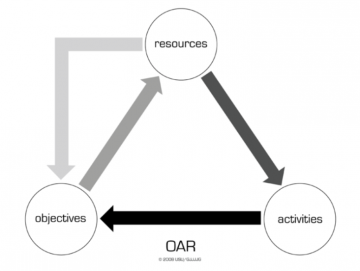

OAR: Objectives, Activities & Resources

The OAR model is a visual tool developed by Joeckel III, Joen and Gardner, instructional designers at Utah State University, which specifically applies to instructional development for courses housed within an online learning platform. It emphasizes the relationships between Objectives, Activities and Resources, to ensure that this dynamic is faithfully represented within an online learning experience.

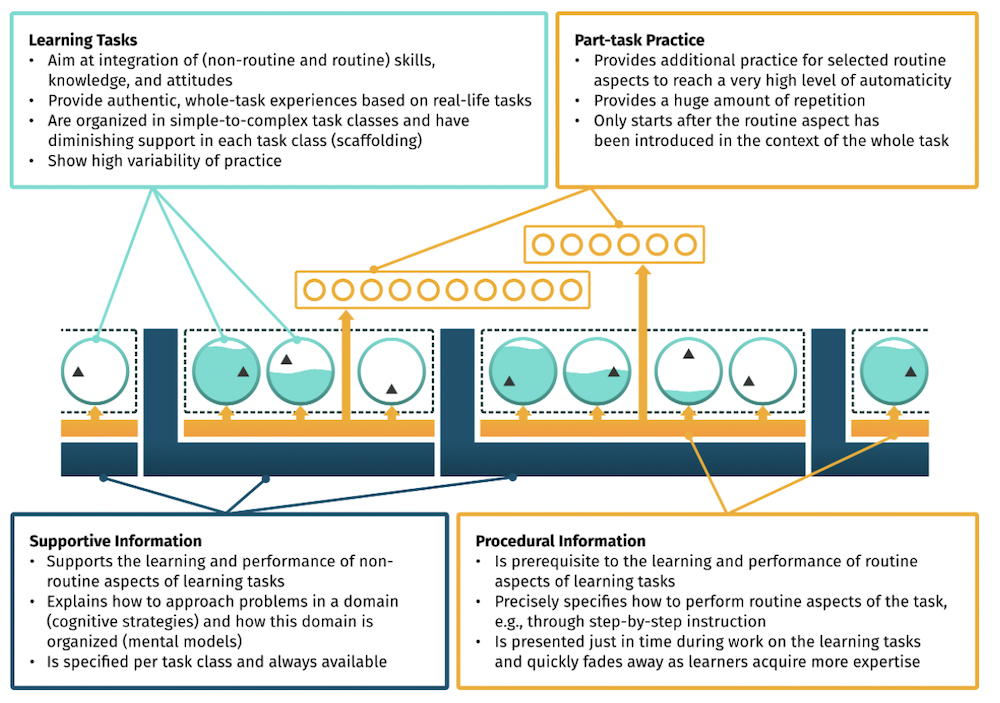

The Four-Component Instructional Design

This model, developed by Dutch researcher Van Merriënboer in the early 1990s (Van Merriënboer, J. J. G., Jelsma, O., & Paas, F., 1992) is a model that focuses on instructional design for training contexts in which new skills are taught in a systematic way. As this model The idea behind this model is to break down training of competencies into four parts:

- Learning tasks and actviites aimed and providing authentic learning experiences

- Supportive information that supports novel ideas and concepts covered in the learning tasks

- Procedural Information focusing on how to perform tasks (tied to learning tasks)

- Part-task Practice allows students to complete new tasks with a fading level of support until learners become experts.

For more details check out this report on the 4CID.org website.

Key Take-Aways

- Instructional Design and it’s successor terms are useful to understand to be able to ‘talk the talk’ when engaging in this work and to understand trends in how educators are thinking about the work of designing learning experiences.

- There are many different models of how to engage in Instructional or Learning Design work. These models may be adapted by different units in a workplace, or simply may serve as an internalised reference for how individuals conduct this work. When combined with what we know of how people learn and how to choose technology, these concepts give us a much more rounded skillset as an Instructional or Learning Designer.

Closing Questions

First, revisit the title of this chapter. What is Learning Experience Design? Spend a few mins in you head, or using a pen and paper to jot down your answer to this question, or better yet, explain the concept to a family member. If you can explain it well, so they can understand, you’ve probably got a good idea of the concepts presented here.

- Have you been using these terms or models in your own work? Did you know it?

- What are the pros and cons of each model? Which one do you prefer and why?

- When considering terminology, what would you want your job title to be? How does it represent the work you do?

Conclusion / Next Steps

Moving forward, feel free to explore more about models of Instructional and Learning Design. It’s completely fine if you think some of these models are useless in the workplace, that you don’t agree with how they’re articulated. In your future work, this about how you might ‘pick and choose’ from different models to ensure that your work meets the needs that you want to focus on, whether it be assessment, activity design, presentation of learning materials or more affective aspects, like how much fun your learners are having, how your lessons might celebrate diversity or facilitate collaboration.

References

Agostinho, S., Lockyer, L., & Bennett, S. (2018). Identifying the characteristics of support Australian university teachers use in their design work: Implications for the learning design field. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 34(2). https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.3776

Bennett, S., Agostinho, S., & Lockyer, L. (2016). The process of designing for learning: understanding university teachers’ design work. Educational Technology Research and Development, 65(1), 125–145. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-016-9469-y

Agostinho, S. (2006). The use of a visual learning design representation to document and communicate teaching ideas (L. Markauskaite, P Goodyear, & P. Reimann, Eds.; pp. 3–7). http://ro.uow.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2176&context=edupapers

Bennett, S., Agostinho, S., & Lockyer, L. (2016). Investigating University Educators’ Design Thinking and the Implications for Design Support Tools. Journal of Interactive Media in Education, 2016(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.5334/jime.404

Churchill, D., King, M, & Fox, B. (2013). Learning design for science education in the 21st century. Journal of the Institute for Educational Research, 45 (2), 404-421.

Dick, W., Carey, L., & Carey, James O. (2009). The systematic design of instruction (7th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill/Pearson.

Joeckel III, G.L. & Jeon, T & Gardner, PhD, CPT, Joel. (2009). Instructional challenges in higher education online courses delivered through a learning management system by subject matter experts. 273-283. 10.4018/978-1-61520-672-8.ch016.

Tyler, R.W. (1949). Basic principles of curriculum and instruction. Chicago: University of Chicago Press

Van Merriënboer, J. J. G., Jelsma, O., & Paas, F. G. W. C. (1992). Training for reflective expertise: A four-component instructional design model for complex cognitive skills. Educational Technology Research and Development, 40(2), 23–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02297047

Further Reading (optional)

Jahnke, I., Riedel, N., Singh, K., & Moore, J. (accepted 2021, February 14). Advancing sociotechnical-pedagogical heuristics for the usability evaluation of online courses for adult learners. Online Learning Journal.

Did this chapter help you learn?

100% of 9 voters found this helpful.

Provide Feedback on this Chapter