How do we evaluate Learning Communities, and what comes next?

Overview

After the COVID-19 pandemic when everyone was forced to ‘pivot’ to online learning, this caused a sea change in how people perceived technology in the support of learning. In this chapter we’ll examine what learning communities in online spaces might look like in the future, and how we may evaluate learning communities we establish and facilitate.

Learning Outcomes

After working through this chapter, you’ll be able to:

- Identify methods to evaluate an online learning community

- Consider how physical location may affect participation in a learning community.

- Explore how learning communities may evolve in the future

- Examine emerging technologies for their potential for learning communities

Why is this important?

When engaging in the design and facilitation of a learning community, the goal is always to enhance learning and to provide learners with a supportive, engaging and (dare we say it) fun environment. Determining whether our efforts have been successful is incredibly important in honing our facilitation skills as well as refining the decisions we make in how we design and implement learning communities. For this reason, it’s important to have an understanding of what we should look at when evaluating learning communities, while at the same time being aware of what’s on the horizon and how we can leverage emerging pedagogies and technologies to support learning.

Guiding Questions

As you’re reading through these materials, please consider the following questions, and take notes to ensure you understand their answers as you go.

- What would you want to know from your students about their experiences in a learning community?

- What questions would you ask?

- Do you consider your current approaches and / or experiences with OLC’s innovative? What will this look like in the future?

Key Readings

Ke, F., & Hoadley, C. (2009). Evaluating online learning communities. Educational Technology Research and Development, 57(4), 487-510.

Evaluation of Learning Communities

Ke and Hoadley (2009) reviewed a series of studies to summaries methods for evaluating learning communities and found these approaches focused on a few themes, outlined below:

- Usability: In terms of technology, how usable and intuitive was it in orienting and facilitating members of the learning community?

- Learning Achievement: What were the effects on learning outcomes (e.g. assessment scores, exam scores) that were observed based on participation in the learning community?

- Connectedness: How connected did the learners feel to one another?

When we examine the above factors, it’s obvious that they are interrelated, so this needs to be taken into account as we collect and look at information about student experience when engaging in an online learning community.

Paloff and Pratt (2010) also outline that ‘debriefing’ with students after their learning experience is a good thing to do to (p.23) as this allows the instructor and learners to have a frank conversation about how any online collaborative exercise went. Forms this could take include:

- informal conversation with groups;

- surveys and reflections for learners on multiple levels

- practical level (e.g., “how did the group work together?”)

- metacognitive level (e.g., “how did the group work help you to form new understandings and problem solve?”)

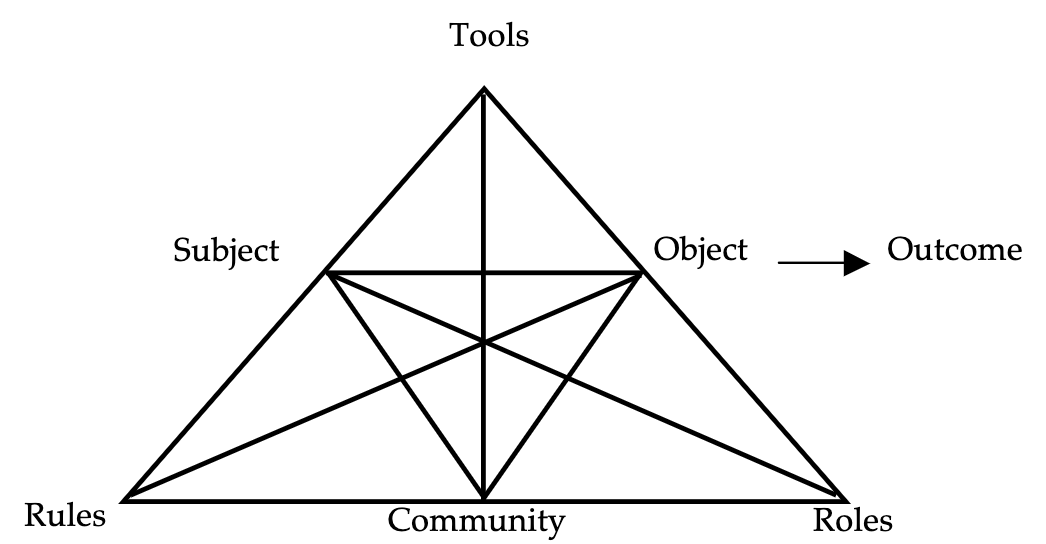

Additionally, other researchers over the years have looked at how to evaluate online learning communities. Hew and Cheung (2003) developed a model nearly 20 years ago that allows us to think about the community in terms of technologies, social roles and rules, how all this relates to outputs of the group. This is a useful thing to consider as we look at evaluating our practice, because it can give us focus beyond ‘was this community effective?

Technology Acceptance

In the late 80s and early 90s, Davis and his colleagues developed the Technology Accceptance Model (Davis, 1989; Davis, Bagozzi, & Warshaw, 1989). This included two concepts around why people may or may adopt the use of a technology: 1) Perceived usefulness and 2) Perceived ease of use. Based on this long-established model of understanding why people use certain technologies and not others, Teo (2003) expanded this model to specifically look at online learning communities. As you can see below, the model shows us the myriad of factors that go into how learning communities operate. By exploring any number of these factors, we can start to evaluate the experiences of our learners to understand if the community is having the effect we desire.

Does inclusive practice matter?

While this is a rhetorical question, its important that we look at learning communities as well as communities of practice from an equity and inclusion standpoint and learn as much as we can about every learner’s experience to ensure the information we gather actually represents all learners. There are a plethora of reasons why a student may choose not to engage in an online discussion or learning community outside that of other time commitments. Accessibility issues with technology, power dynamics and structures, gender, age, and many other intersecting factors may play a role in how a learning community is perceived by learners and therefore how much they choose to engage. Simple questions such as “Do you feel connected?” are important to answer, however we also must strike a balance between invasive questions that may make our learners feel uncomfortable and making a space where learners are comfortable to share their experiences so that we may learn from them.

For more in the topic of access and inclusion, check out Access, Inclusion, and Learning Technology

Using Data to inform our practice

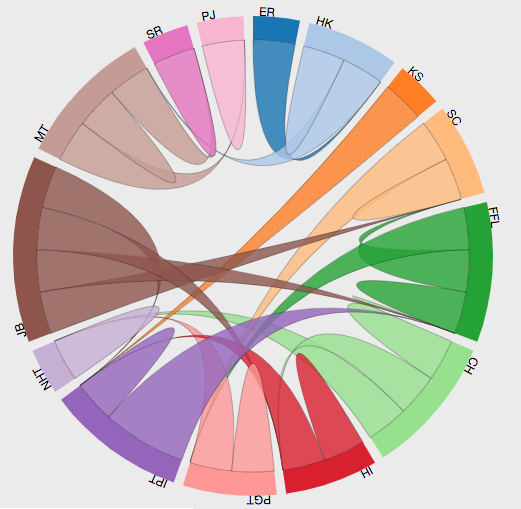

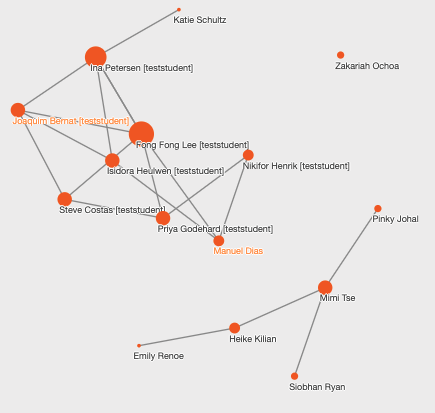

An emerging area of practice within business and education is the use of data to both learn about what people are doing, and to understand how our actions and interventions may affect learner behaviour. In this space, educational data and learning analytics can provide educators and educational leaders with insights into how learners engage within a learning community. While most of this data comes in the form of CSV (Comma separated value) files, which are basically a bunch of text, many online learning technologies and platforms allow for this data to be accessed quite easily in the form of graphs and other visualisations (below). Taking a look at this data can provide insights into our learning communities , giving us ‘behind the curtain’ view of things, by visualising interactions and what they mean for learning. This is usually referred to Social Network Analysis (SNA for short – for a review see Cela et al., 2020). In this case, social network doesn’t refer to facebook, twitter and the like, but simply the network that is derived from social interactions in an online space. For example, looking at the visualisations below, and instructor might easily be able to discern who is engaging more than others, which students are talking to their peers more and how much they are saying. Such insights can help us to consider different interventions that may increase engagement, include more students in the conversation, and other strategies to improve our practice.

For more on how educational data and learning analytics can support our use of technology, check out Introduction to Learning Analytics

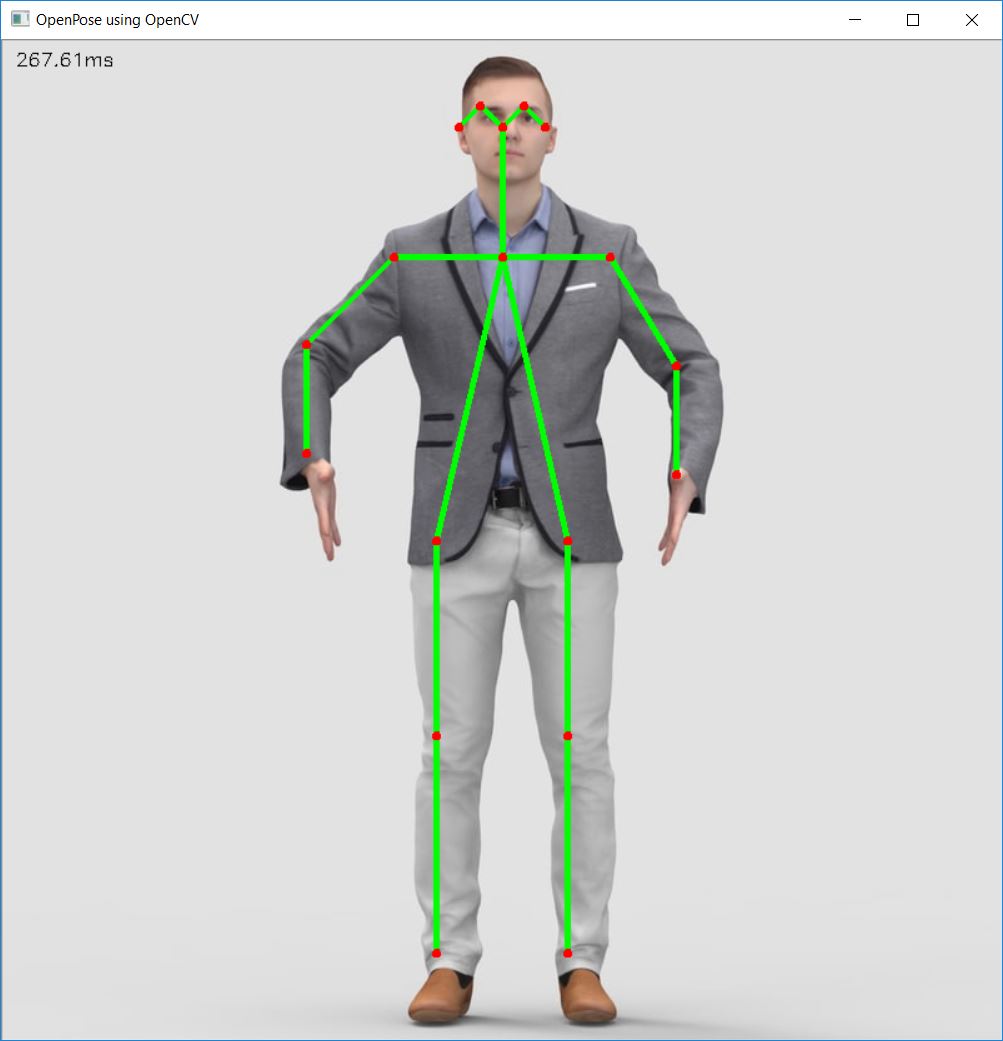

These visualisations presented above are based on the established text-based technologies of discussion forums, which have been the standard means for learners to interact with each other for years. When it comes to more dynamic technologies such as video chat and other forms of engagement, there are means to analyse this information as well, but it looks quite different, coming in the from of something called MMLA or Multi-Modal Learning Analytics. Instead of text-based data, MMLA uses other forms of information, including audio and video recordings to analyses and further understand group engagement both online and in physical spaces.

Check out the Transformative Learning Technologies Lab (TLTL) at Northwestern University in the US if you’d like to learn more.

Physical vs. Online Learning Communities

Before we launch into the sci-fi dreams of what learning communities will look like in the future, it’s important to acknowledge the effects the COVID-19 pandemic had on teaching and learning. For many of us who teach and learn in physical environments like classrooms and workplaces, learning communities were simply a byproduct of being together – organic social interactions that come about by those in a shared physical space. While the obligatory ‘team building exercise’ may have made us grind our teeth, these in person experiences allowed us to engage, read body language and facial expressions, hear tone of voice, and see the product of our collaboration much more concretely. As we moved online, something was lost – perhaps something we took for granted.

In an online environment, much of the organic interaction cannot happen because we don’t have that physical space that we inhabit – these things need to be intentionally designed and created by those doing the teaching, designing and facilitating of the learning experience. For this reason, examining learning communities in different modalities will obviously look different, and how we support and engage with each other obviously looks different too.

COVID-19: During the Pivot to Online

During the pivot to online learning, community became incredibly important to teachers and students alike. For teachers conversations evolved in professional learning communities from simple sharing to tools to be more about online teaching and learning pedagogy, as well as support for other professional practice and even wellbeing (Tucker and Quintero-Ares, 2021). In Lemay and Doleck’s (2020) analysis of Twitter hastags #onlineteaching and #onlinelearning during the pivot, there was of course frustration expressed by many posts and replies were positive and encouraging also.

Anderi et al. (2020) explored how medical students in America were able to connect with each other as well as physicians and residents to learn more about COVID-19 as it was happening. This article presents one of the most powerful aspects of online communities – the ability to connect with people beyond the physical classroom, to include guests from external locations, external organisations and those actually doing the work in the field, something that not enough formal learning experiences offer.

What comes next?

As educational institutions eased their way out of the pandemic, there was much discussion around Digital Transformation and Digital Innovation (as if technologies to support online learning had not existed before COVID-19 😉). In many instances this brought on organisational change to adapt to the changing work and learning structures that were necessary to protect public health, while in other contexts, the pivot to online was only ever seen as temporary, such as in schools where the prevailing model was and continues to be face-to-face learning, for obvious reasons.

Communication Technologies

As technology has evolved to allow learning communities to first communicate, then collaborate and co-create, the next evolution in the role that learning communities play is important to consider. Will be technical in nature, pedagogical in nature or both? First, if we consider advances in technology for communication and collaboration, these are only getting better, allowing for real-time video on our computers and mobile devices. Video chat tools such as Zoom now have very little lag (slowdown that negatively affects discourse) brings us closer to more natural conversations, being able to use ‘micro-interruptions’ to talk with each other and see each other’s faces. While it’s still a bit awkward, and we can’t all stand around in the hallways or around a table yet, the audio and video aspects are getting there.

The use of mobile technologies has definitely allowed us to communicate more conveniently. While many of us use technologies like text messaging, WhatsApp, Facebook Messenger, and WeChat to keep in touch, these technologies didn’t really penetrate education in any meaningful way. Other text-based chat tools such as Slack, Discord and Mattermost did make inroads with educators as they provided a more mobile-friendly and agile experience for learners.

Chatbots

As an extension of these tools, Chatbots – algorithms that provide automatic responses to student questions in platforms like this – have been in use for years, but primarily for research purposes (Heller et al., 2005). In a nutshell, a chatbot allow students to ask questions (e.g., “When is X assignment due?”) and will answer the question as if a real person is responding. This technology has been in use for years in the private sector (you may have interacted with one yourself), however their prevalence in education is still not high.

Chatbots, in all honestly provide the illusion of engagement either with an instructor, or with an unnamed ‘robot’, but can nevertheless create a sense of teacher and social presence for learners, even when there is no flesh and blood person behind the response.

Immersive technologies

Advances in Extended Reality (XR) are now allowing for real-time collaboration in Virtual and Augmented Reality environments, and while this technology is not ubiquitous yet, as more and more companies start to roll out their solutions in this space, communities will no doubt pop up around it. In addition, the concept of a ‘metaverse’, an online and virtual 3D world akin to a social network is also gaining traction among the likes of Meta (owners of Facebook) and other large tech firms.

Key Take-Aways

- Evaluating a learning community’s effectiveness means that we need to look at the overall outcomes and achievement of the learners combined with aspects of how the learning community contributed to these outcomes

- Technology-enabled face-to-face communities are very different to online communities, so the evaluation methods we use for both should be different

- Established and emerging technologies such as mobile tech, chats, and immersive technologies like VR, XR can give us a path forward in how learning communities are

Revisit Guiding Questions

There is much we can learn from students and the technologies we use to engage in online learning communities. Consider how learning communities that you use might allow for certain interaction and collaborative activities and ponder what questions you might ask your learners to reflect on and built upon what you’ve created. Additionally, what information can the technology itself provide to help answer the questions you have, and how will this change in the future?

Conclusion / Next Steps

As we wrap up this book, the exploration of learning communities including how they work, how they can work in the future and the role they play in learning will continue to be explore both by researchers and teachers ‘in the trenches’. Pedagogically, understanding how learning communities can benefit learners, and their experience in the creation of assessment artefacts and other assets is an important thing to think about. Are they a ‘nice addition’ or are they required for learners to get the most out of their experience?

References

Anderi, E., Sherman, L., Saymuah, S., Ayers, E., & Kromrei, H. T. (2020). Learning communities engage medical students: a COVID-19 virtual conversation series. Cureus, 12(8)

Cela, K. L., Sicilia, M. Á., & Sánchez, S. (2015). Social network analysis in e-learning environments: A preliminary systematic review. Educational Psychology Review, 27(1), 219-246.

Davis, F.D., 1989. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information

technology. MIS Quarterly 13 (3), 319–339.

Davis, F.F., Bagozzi, R.P., Warshaw, P.R., 1989. User acceptance of computer technology: a comparison

of two theoretical models. Management Science 35 (8), 982–1003

Heller, B., Proctor, M., Mah, D., Jewell, L., & Cheung, B. (2005, June). Freudbot: An investigation of chatbot technology in distance education. In EdMedia+ innovate learning (pp. 3913-3918). Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE).

Hew, F. H., & Cheung, W. S. (2003). Models to evaluate online learning communities of asynchronous discussion forums. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 19(2), 241-259.

Lemay, & Doleck, T. (2020). Online Learning Communities in the COVID-19 Pandemic: Social Learning Network Analysis of Twitter During the Shutdown. International Journal of Learning Analytics and Artificial Intelligence for Education (iJAI), 2(1), 85–. https://doi.org/10.3991/ijai.v2i1.15427

Palloff, R. M., & Pratt, K. (2010). Collaborating online: Learning together in community (Vol. 32). John Wiley & Sons.

Teo, H. H., Chan, H. C., Wei, K. K., & Zhang, Z. (2003). Evaluating information accessibility and community adaptivity features for sustaining virtual learning communities. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 59(5), 671-697.

Tucker, L., & Quintero-Ares, A. (2021). Professional learning communities as a faculty support during the COVID-19 transition to online learning. Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration, 24(1), 1-18

Further Reading

Did this chapter help you learn?

No one has voted on this resource yet.

Provide Feedback on this Chapter