How can we move towards ILxD?

Overview

In the last few chapters we’ve explore how we can identify immediate and potential barriers to student learning and to design, both from a pedagogical and technical perspective, how we can reduce barriers and increase access for our students. This chapter will extend beyond this idea of access to move toward inclusivity and empowerment for all students, not just based on ability, but personal history and culture.

Learning Outcomes

- Understand how Inclusive teaching can situate ourselves as teachers

- Explore culturally-informed and trauma-informed pedagogy

- Examine advances in learning technologies that will support inclusivity and access moving forward

Why is this important?

Since early 2020, an emphasis on care for students has been part of the teaching and learning discussion. Within the context of global pandemic, more attention started to be paid to teaching the whole student not just the one that produces assessment artefacts and engaged (or didn’t engage) in class. When considering the design of technology-enabled and online learning experiences for our students, we should be mindful of how inclusivity, care and other factors can be folded into our practice so that we can advance beyond access to a celebration of diversity and normalised inclusion in our pedagogy.

Guiding Questions

As you’re reading through these materials, please consider the following questions, and take notes to ensure you understand their answers as you go.

- What have you done in the past to celebrate the diversity of your students?

- How do you think this could be done with technology?

- What barriers, if any, could manifest based on the careful use of technology we’ve considered in previous chapters?

Key Readings

Funk, J. (2021). Caring in Practice, Caring for Knowledge. Journal of Interactive Media in Education, 2021(1). https://doi.org/10.5334/jime.648

Harrison, N., Burke, J., & Clarke, I. (2020). Risky teaching: developing a trauma-informed pedagogy for higher education. Teaching in Higher Education, 1-15.

Richards, H. V., Brown, A. F., & Forde, T. B. (2007). Addressing diversity in schools: Culturally responsive pedagogy. Teaching Exceptional Children, 39(3), 64-68.

Key Terms

Adapted from Inclusive Teaching, a class produced at UBC (Vancouver Canada) in partnership with Queen’s University Kingston Ontario licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0

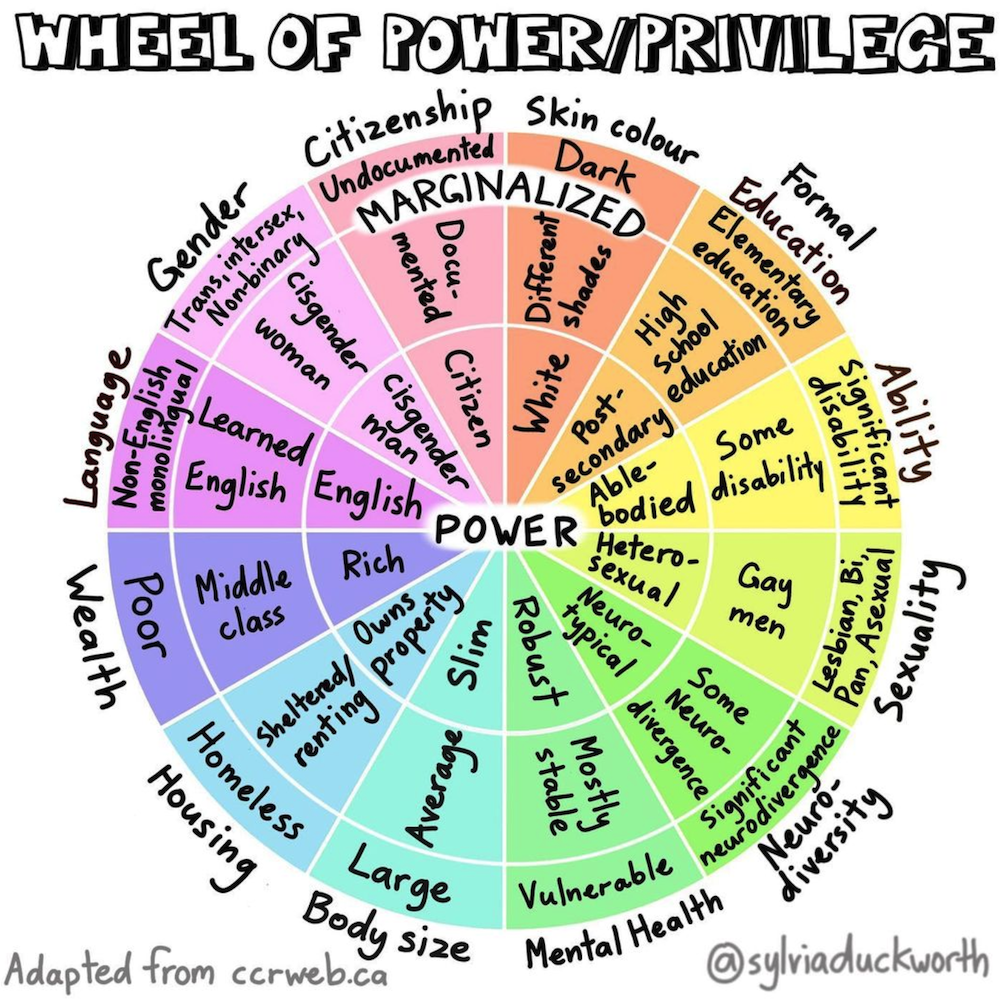

- Power is unequally distributed globally and in society; some individuals or groups wield greater power than others, thereby allowing them greater access and control over resources. Wealth, whiteness, citizenship, patriarchy, heterosexism, and education are a few key social mechanisms through which power operates. Although power is often conceptualised as power over other individuals or groups, other variations are power with (used in the context of building collective strength) and power within (which references an individual’s internal strength). Learning to “see” and understand relations of power is vital to organising for progressive social change.

- Privilege can be defined as a group of unearned cultural, legal, social, and institutional rights extended to a group based on their social group membership. Individuals with privilege are considered to be the normative group (such as those belonging to cisgender, white, able-bodied and other dominant groups), leaving those without access to this privilege invisible, unnatural, deviant, or just plain wrong. Most of the time, these privileges are automatic and most individuals in the privileged group are unaware of them. Some people who can “pass” as members of the privileged group might have access to some levels of privilege.Having privilege does not mean that you never encounter hardship, but rather that the hardship that you encounter is not a result of your belonging to a privileged social group.

- Oppression is the systemic and pervasive nature of social inequality woven throughout social institutions as well as embedded within individual consciousness. Oppression fuses institutional and systemic discrimination, personal bias, bigotry and social prejudice in a complex web of relationships and structures that shape most aspects of life in our society.

- Inclusion is the active, intentional, and ongoing engagement with diversity, where each person is valued and provided with the opportunity to participate fully in creating a successful and thriving community. It also means creating value from the distinctive skills, experiences and perspectives of all members of our community, allowing us to leverage talent and foster both individual and organisational excellence.

- Diversity In broad terms, diversity is any dimension that can be used to differentiate groups and people from one another. It means respect for and appreciation of differences in ethnicity, gender, age, national origin, ability, sexual orientation, faith, socio-economic status and class. But it’s more than this. It includes differences in life experiences, learning and working styles and personality types that can be engaged to achieve excellence in teaching, learning, research, scholarship and administrative and support services.

- Equity is the guarantee of fair treatment, access, opportunity, and advancement for all. It requires the identification and elimination of barriers that prevent the full participation of some groups. This principle acknowledges that there are historically under-served and underrepresented populations in the social areas of employment, the provision of goods and services, as well as living accommodations. Redressing unbalanced conditions is needed to achieve equality of opportunity for all groups.

What is Inclusive Teaching?

Inclusive teaching has its origins in culturally responsive teaching (see below), which acknowledges the importance of when teachers are responsive to culturally diverse students in all aspects of learning – inclusive teaching applies to all forms of differences, including culture, race and ethnicity, age, ability, gender, sexuality, socio-economic status (SES) and other individual and social differences.

In the video below, Shelley Moore describes what inclusive education can do using bowling as an analogy.

As the Centre for Research on Teaching and Learning at Michigan State University outlines, inclusive or equity-based teaching is a strategy that allows teachers to acknowledge and disrupt historical and contemporary patters of educational disenfranchisement that particularly affects marginalised and minority populations. This has to do with ensuring equal access (which we have already discussed in this book), ensuring all students feel valued in their learning environments, experience equality in learning outcomes, share the responsibility for ensuring equitable experiences within the learning community.

The centre also notes that Inclusive teaching:

- is relevant in every discipline

- requires deliberate practice over time with the intention of changing how

- is less about particular pedagogical approaches, but the foundational intention we have as teachers that shape our approaches

The following video discusses how a university teacher experienced a sense of social belonging and how we can support students to increase their sense of belonging, based on the work by Walton and Cohen (2011).

Situating Ourselves

Over 20 years ago, Cook (2001) explored teacher perceptions of students with varying levels of disabilities and found that students with mild or ‘hidden’ disabilities were treated with less tolerance than those with visible and observable disabilities, with more criticism, and less instructional-based interaction, for example. While this chapter or this book does not focus on special education techniques or practices, we as educators using technology need to be aware of this, and how any conscious or unconscious bias in our own minds towards the concept of a ‘normal’ student may play into our design, creation and use of technologies in the technology-enabled classroom or online.

It’s important therefore to consider who we are, both our personal identities (how we perceive ourselves, including interests hobbies, experiences and choices) as well as our social identities (how we understand ourselves as a part of a social group such as religion, ethnicity, gender, etc.). As Barnett outlines, a white, male teacher who grew up in Melbourne, and whose dominant language is english is positioned very differently than a black, female student who grew up in Nairobi, and whose third language is english.

Additionally, our identities are not singular, but rather our identities are multiple, overlapping, and intersecting. This intersectionality can fundamentally alter how social inequities are experienced, and how our individual realities are grasped, all of which come into play in our interactions in the learning environment.

Curry-Stevens (2007) developed a framework to situate ourselves, including our identity and positionality (where we are positioned in society compared to others), which can help to inform the decisions we make as teachers.

| Stage of Learning | What it is |

|---|---|

| Awareness of oppression | “I understand how inequality exists and I can name it oppression.” |

| Oppression as structural and thus enduring and pervasive | “I understand how power is at work to create this oppression. |

| Locating oneself as oppressed | “I have been a victim of discrimination and I have felt heard and support in my pain about this.” |

| Locating oneself as privileged | “I also have privileged identities. I have been on the beneficiary end of power inequities.” |

| Understanding the benefits that flow from privilege | “My privileged identities has allowed me to benefit from these unjust structures and to succeed in my life in the following ways… This means I might not have been as responsible for my achievements as I have understood in the past.” |

| Understanding oneself as implicated in the oppression of others and understanding oneself as an oppressor | “I am responsible for the continued oppression of others either through what I do or what I fail to do.” |

| Building confidence to take action—knowing how to intervene | “I can step forward with ideas about what to do to create change.” |

| Planning actions for departure | “I will do this when I leave.” |

| Finding supportive connections to sustain commitments | “I have some connections to others who will support me in this work. I know where to go to connect to others who are working on this topic.” |

| Declaring intentions for future action | “I announce to others what I plan to do when I leave. Making this commitment to others raises expectations that I will do it.” |

While these are sometimes a difficult conversations to have or even challenging ideas to read about, the video below from the Give Nothing campaign of the New Zealand Human Rights Commission provides a comedic while confronting take on bias and by extension what we may potentially bring with us into the classroom. We may have been socialised to have differing opinions of other individuals we interact with by no fault of our own based on our own culture, upbringing or socio-economic status, but it’s up to us to acknowledge that our own biases (whether conscious or unconscious) exist and to be be mindful of the role they may play in our actions as educators, even if we aren’t acutely aware of them.

In the video below, Anthony Abraham Jack, Assistant Professor at the Harvard Graduate School of Education speaks about how some educational institutions continue to “privilege privilege” – in other words how educational organisations and institutions prioritise students who come to an educational experience with the privilege of being able to do so with an understanding how it works (e.g., study skills, expectations, etc.), while forgetting about and not supporting those who do not. Much of this is based on the assumption that all students come from the same place, while it’s obvious they do not.

What is ILxD?

Learning Design refers to the design of learning experiences including the practices surrounding the process of creating lessons, activities, assessment activities and learning materials, as well as any documentation that supports the process. This term is sometimes interchangeable with instructional design.

Learning Experience Design (LxD) reframes the above concept to think about designing learning experiences for students (as we cannot actually design learning). There are many terms thrown around related to instructional design, so it’s important to think about how we can

Inclusive Learning Experience Design (which is not a commonly used term) extends LxD further to consider access, inclusion, care, wellbeing and other factors.

For more on LxD, check out the chapter What is Learning Experience Design (LxD)?

Individual Differences

Meyer & Rose (2002) discuss individual differences in learners through the lens of disability and UDL, however in recent years, the thinking around individual differences has become more accepting of the fact that disability is but one minute aspect of how we can think about individual differences in learners.

Conceptions of how memory and learning works have also evolved beyond notions of disability vs ability to acknowledge that based on previous experiences, human variation and learning environment individuals can differ both in how they process information and how they learn. Sepp et al. (2019) assert that based on these factors, how and what we pay attention to when problem solving and learning could be a factor of our experiences, suggesting that all of our abilities are different – not in a ‘have’ or ‘have not’ sense, but simply to the fact that there is variation in all individuals.

Additionally Zacher & Rudolph (2020) highlight that there are even individual differences in how individuals have interpreted, coped and taken care of ourselves from a wellbeing perspective during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Representation of Diversity

How students see themselves within a unit of learning, and within their learning context means a lot too. If paper-based or digitally-presented learning materials fail to present the reality of diversity within the student population, this may lead to feelings of lack of inclusion, and by extension a lack of motivation to engage. Check out 2022’s Australian of the Year, Dylan Alcott speak about how representation affected him as he was growing up.

When teaching using technology, it’s therefore important to be mindful of who is represented, both in terms of the materials we use, as well as the language we use. Incorporating viewpoints of people from non-dominant culture can mean a lot when it comes to learners seeing themselves in the learning experiences they’re engaging in.

As an example of this in practice, check out Mind the Gap a handbook for medical students on the clinical signs of certain pathologies as they manifest on black and brown skin. This project was spearheaded by students, simply because they noticed that almost all the learning materials they would see as medical students were of white skin.

Representation in Enrolment

Representation in enrolment, especially in STEM education domains (particularly technology and engineering, see European Commission, 2015) is a long-documented and researched topic. Ertl et al. (2017) documents how gender stereotypes affect female students and their self-perception, so while we assume that this issue is progressing, it is very much still here. This highlights and interesting point, that as norms and often damaging persisting stereotypes can affect learners in different ways, we need to be mindful of how historically marginalised groups are included and reflected in their educational experiences. My intentionally changing an activity, learning material or other aspect of our teaching practice, we can ensure that we’ve been actively inclusive of these learners, to ensure that they see themselves in their learning experience, and not as an ‘other’.

Culturally-informed Pedagogy

Education looks different cross cultures and how we perceive these learning experiences as well as the roles we play, from instructor to learner different. There may be different power dynamics, expectations for engagement, performance and other factors to consider. Richards et al. (2007) refer to culturally responsive pedagogy as “effective teaching and learning [that occurs] in a culturally supported, learner centred context, whereby the strengths students bring to [the learning] are identified, nurtured, and utilised to promote student achievement.”

The National Strategic Framework for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples’ Mental Health and Social and Emotional Well-being 2017-2023, outlines important cultural competencies. The following have been adapted from p.15 of this document.

- Cultural Awareness: Understanding the role of cultural difference and diversity…This means the capacity for self-reflection as to how the Western dominant culture impacts on both themselves and [other] people, and can impact the service setting they operate in.

- Cultural Respect: Valuing [other] people and [non-dominant] cultures. This includes a commitment to self-determination and building respectful partnerships.

- Cultural Responsiveness: Having the ability and skills to assist people of a different culture other than your own.

All of these competencies are tied to creating a safe space for all people to learn in. As Gay (2015) outlines:

“no ethnic group should have exclusive power, or total cultural and political dominion over others, even if it is a numerical majority. Rather, ethnic, racial, cultural, social, and linguistic pluralism is considered as a natural attribute of humankind, as a fundamental feature of the democratic ethos (whether as an ethic of community living or a structure of government), and as a necessary component of quality education in both national and international contexts. (p. 125)

Trauma-informed pedagogy

One increasingly common practice in education is to consider our learners from a more empathetic perspective, taking into account their past and current experiences and the effects they have on learning. Hoch et al (2015) describe trauma as “any experience in which a person’s internal resources are not adequate to cope with external stressors” with Davidson (2017) outlining the form this could take (p.4).

- Physical or sexual abuse

- Abandonment, neglect, or betrayal of trust (such as abuse from a

- primary caregiver)

- Death or loss of a loved one

- Caregiver having a life-threatening illness

- Domestic violence

- Poverty and chronically chaotic housing and financial resources

- Automobile accident or other serious accident

- Bullying

- Life-threatening health situations and/or painful medical procedures

- Witnessing or experiencing community violence, including shootings, stabbings, or robberies

- Witnessing police activity or having a family member incarcerated

- Life-threatening natural disasters

- Acts or threats of terrorism (viewed in person or on television)

- Military combat

- Historical trauma

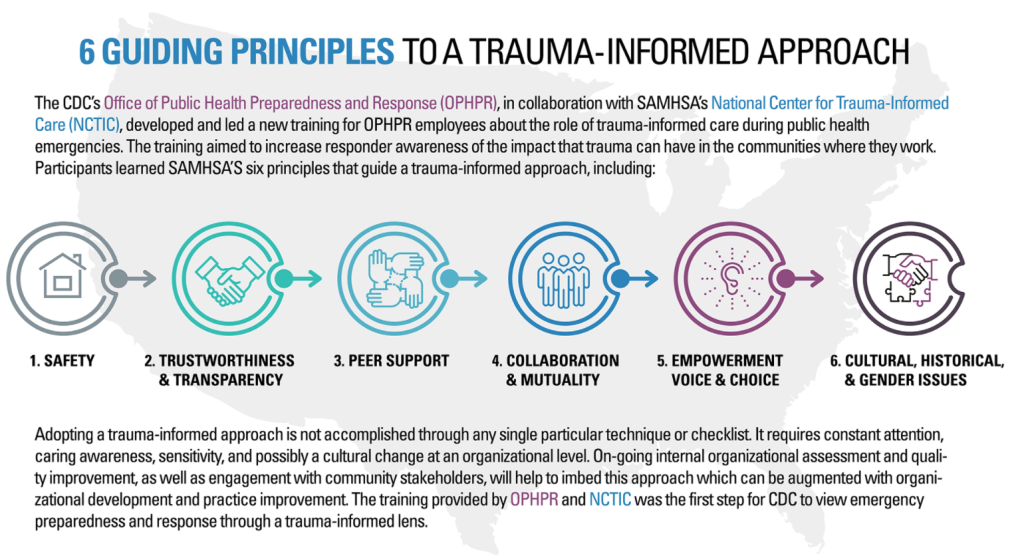

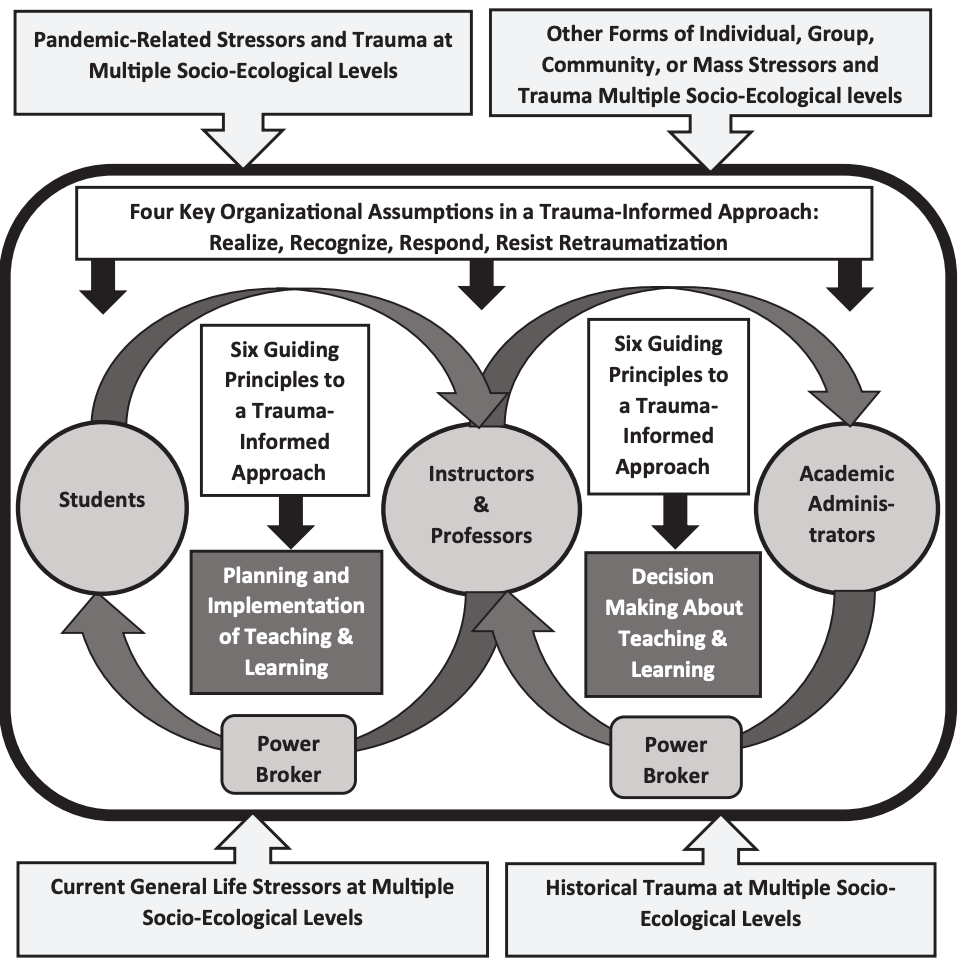

While there has been much research and writing on trauma-informed pedagogy over the years, Harper and Neubauer (2020) recommend the United State’s Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s (SAMHSA) model within the context of the COVID-19 pandemic as an appropriate model to draw upon. Additionally, Anderson and Thrave’s guide above provide many actionable approaches for promoting wellbeing.

As a related or extension of trauma-informed pedagogy, a growing body of research and work is being conducted on Care-based Pedagogy, mainly motivated by changes in education brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic. For more on care-based pedagogy (or pedagogy of care) see What are the Emerging Trends in Pedagogy?

Inclusive Pedagogy for Student Wellbeing

While this unit is more about technology and its role in promoting access and inclusion in educational settings, we should first familiarise ourselves with basic understandings of inclusive pedagogies. Researchers at the University of New England, Australia, Dr. Joanna Anderson and Dr. Genevieve Thraves recently developed an Instructional Design plan for Inclusive Pedagogy for Student Wellbeing. If you’re interested, take a look at the materials below.

- Inclusive Pedagogy for Student Wellbeing Video presentation – 22mins)

- Inclusive Pedagogy for Student Wellbeing Instructional Design Plan (PDF 3MB)

Learning from Country

One unique opportunity for the Australian context in terms of culturally-informed pedagogy is the opportunity to embed indigenous knowledge, worldviews and languages into our lessons. A simple first step is to include a digital acknowledgement of country, with a prompt for students to share online (in chat or verbally) the Country that they’re living on.

We can also include instructional elements such as the 8-Ways framework, developed by Yankaporta. Additionally, our location can also present many opportunities for learning, especially online, for learners (including aboriginal, settler / colonist descendent or immigrant) to share a learning experience specific to their own physical surroundings in the form of Place-based Learning. For more, check out the video below or check for details on how mobile learning can relate to Place-based pedagogies, check out the chapter ‘What are the emerging trends in Pedagogy?‘

Care-based Pedagogy

As Schwartzman (2020) found in his ethnographic study of hist home-based students during the COVID-19 pandemic, that the pandemic itself and the experience of students simply shone a light on inequities that were already there, ranging from the digital divide (e.g., inequalities in skills, access and literacies in the use of digital technologies), to what he frames as a neoliberal mindset of education systems themselves – that the problems must lie with the students not the institutions.

The trauma, inequity, and ongoing existing challenges of our students was thus confronted by many educators through what has come to be known as ‘care-based pedagogy’ or ‘pedagogy of care’. This approach takes into account the whole human that is being taught to engage in ‘human centred learning design’ to understand that all learners are unique individuals and we can celebrate their uniqueness and capitalise on it through specific teaching and learning practices. This means that teachers practicing care-based pedagogies generally express empathy for learners’ experience, encourage activities that are designed address student wellbeing and intentionally have a closer relationship with their students. Examples of care-based approaches vary, but could include:

- Differentiation and Personalisation of activities and assessments to to capitalise on student interests (related to UDL)

- Flexible completion options (e.g., alternatives to essays and flexible due dates)

- Including Meditation and Yoga videos in online learning units

- Offering a less formal approach to education (i.e. having more fun approaches in class)

- Hosting Homework Sprints where students work together on homework while listening to music

Using Technology to support inclusion and wellbeing

So how does all this relate to technology? Well, technology provides us with many opportunities to enhance a learning experience, perhaps even beyond what is possible in a traditional on-campus classroom. Technologies with affordances (characteristics the define the actions we can take with them) that allow for increased representation, demonstration of care and humanity, celebration of cultural and linguistic diversity and other factors can help us to embed and bring who are learners are to the surface with the expressed and intentional aim to reconsider who our students are, and their role in education.

Examples in can include the following:

- Inclusion of personal pronouns within a learning platform

- Allowing learners to record the pronunciation of their name through specialised online tools

- The audio of audio and video technology to allow activity and assignment submissions in alternate languages.

- Using learning materials and guest lecture recordings from outside the dominant culture

- Surveys to check in on the wellbeing of students

- Using face filters to make online meetings more fun

- Not requiring students to turn on their cameras during online meetings

- Including videos or having online guest lectures from members of indigenous communities

- Allow students’ creations to be shared openly so that friends, family and community members, regardless of location, can share in their learning and celebrate their achievements

Additionally, the choices we make as educators in the use of technology may unintentionally prolong and exacerbate inequalities that exist for our learners. For example, at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic it was very common during Emergency Remote Teaching (ERT) to require students to have their webcams on at all times, however Moses (2020) outlines 5 reasons why we shouldn’t require cameras to be on.

- Increased Anxiety and Stress

- Online Meeting Fatigue

- Competing obligations and responsibilities

- Right to privacy

- Financial means and other access issues

With all this considered, as we use technology, we should not just consider the opportunities it presents, but also the barriers it may put up, despite our best intensions. By considering all angles in the use of chosen technology and the effects it could have on all learners, we can better critically reflect on what the best choice in technology is, and for what purpose.

Key Take-Aways

- Beyond addressing access issues, we should also consider how to ensure that all students are represented within technology-enabled and online learning environments.

- We can embed culturally responsive practices

- We can ensure that students’ past experiences are taken into account so that they have a supportive learning environment

- We can embed simple strategies to humanise the learning environment, through community, informality and flexiblity

Revisit Guiding Questions

As we consider how to move beyond access, to inclusive and equitable learning environments, have a think about what you can do in your classroom to make sure that all learners are reflected and included in all aspects of teaching, and how technology that you use can be used to do so.

References

Barnett, P. A. (2003). Social identity and privilege in higher education. Liberal Education, 99(3), 30-37.

Cook, B. G. (2001). A comparison of teachers’ attitudes toward their included students with mild and severe disabilities. The journal of special education, 34(4), 203-213.

Curry-Stevens. (2007). New Forms of Transformative Education: Pedagogy for the Privileged. Journal of Transformative Education, 5(1), 33–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/1541344607299394

Davidson, S. (2017). Trauma-Informed Practices for Postsecondary Education: A Guide.

Ertl, B., Luttenberger, S., & Paechter, M. (2017). The impact of gender stereotypes on the self-concept of female students in STEM subjects with an under-representation of females. Frontiers in psychology, 8, 703.

European Commission (2015). She Figures 2015. Available online at: https://ec.europa.eu/research/swafs/pdf/pub_gender_equality/she_figures_2015-final.pdf

Gay, G (2015) The what, why, and how of culturally responsive teaching: International mandates, challenges, and opportunities. Multicultural Education Review, 7(3), 123-139.

Harper, G. W., & Neubauer, L. C. (2021). Teaching during a pandemic: A model for trauma-informed education and administration. Pedagogy in health promotion, 7(1), 14-24

Hoch, A., Stewart, D., Webb, K., & Wyandt-Hiebert, M. A. (2015, May). Trauma-informed care on a college campus. In Presentation at the annual meeting of the American College Health Association, Orlando, FL.

Meyer, A., & Rose, D. (2000). Universal Design for Individual Differences, Educational Leadership, 58(3), 39-43

Moses, T. (2020) 5 Reasons to let students keep their cameras off during Zoom classes. The Conversatio, 17. Retrieved from https://theconversation.com/5-reasons-to-let-students-keep-their-cameras-off-during-zoom-classes-144111

Prensky, M. (2011). Digital natives, digital immigrants. In M. Bauerlein (Ed.), The digital divide:

Arguments for and against Facebook, Google, texting, and the age of social networking (pp. 45–

51). Penguin.

Sepp, S., Howard, S. J., Tindall-Ford, S., Agostinho, S., & Paas, F. (2019). Cognitive load theory and human movement: towards an integrated model of working memory. Educational Psychology Review, 31(2), 293–317. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-019-09461-9

Schwartzman, R. (2020). Performing pandemic pedagogy. Communication Education, 69(4), 502-517.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2014a). SAMHSA’s concept of trauma and guidance for a trauma-informed approach (HHS Publication No. 14-4884).

Walton, G. M., & Cohen, G. L. (2011). A brief social-belonging intervention improves academic and health outcomes of minority students. Science, 331(6023), 1447-1451.

Zacher, H. & Rudolph, C. W. (2020). Individual differences and changes in subjective wellbeing during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. American Psychologist.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/amp0000702

Further Reading

Fiske, S. T. (2022). Prejudice, discrimination, and stereotyping. In R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (Eds), Noba textbook series: Psychology. Champaign, IL: DEF publishers. Retrieved from http://noba.to/jfkx7nrd

Flynn, A. & Kerr, J. Preparing for a More Inclusive Course: Teaching to Promote Inclusion and Celebrate Diversity. Retrieved from https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/inclusiveeducation/

Did this chapter help you learn?

No one has voted on this resource yet.

Provide Feedback on this Chapter