What are the Emerging Trends in Pedagogy?

Overview

This chapter will provide an overview of innovative approaches to teaching and learning that form the foundation of innovations in learning technology. Without these pedagogical innovations, the affordances of new technologies could not be applied, so relationship between innovative pedagogies and technologies go hand in hand. If the technologies don’t exist, many times we can’t do what we want to do pedagogically, and vice versa.

Given that these two areas are related, feel free to jump ahead to the next chapter, skim both and then dive deep as this approach may give you ideas for your own teaching practice.

Why is this important?

While some teachers still enjoy the ‘chalk and talk’ method of teaching by standing in front of a blackboard, white board or presentation slide deck, there are now many alternate ways of presenting information, engaging with and assessing our learners, so it’s important to have an idea of how teaching and learning has changed over the years, as well as the current trends where pedagogy is moving forward.

Guiding Questions

As you’re reading through these materials, please consider the following questions, and take notes to ensure you understand their answers as you go.

- How did you learn about the practice of teaching?

- What is the role of the teacher supposed to be? What about the learner?

- Should learning be fun, or not?

- Do you think about changing your learners, beyond the subjects you teach them?

Key Readings

Clark, M. C. (1993). Transformational learning. New directions for adult and continuing education, 1993(57), 47-56.

Gikas, J., & Grant, M. M. (2013). Mobile computing devices in higher education: Student perspectives on learning with cellphones, smartphones & social media. The Internet and Higher Education, 19, 18-26.

Nah, F. F. H., Zeng, Q., Telaprolu, V. R., Ayyappa, A. P., & Eschenbrenner, B. (2014, June). Gamification of education: a review of literature. In International conference on hci in business (pp. 401-409). Springer, Cham.

Rose, E., & Adams, C. A. (2014). “Will I ever connect with the students?” Online teaching and the pedagogy of care. Phenomenology & Practice (7) 2, 5-16.

Wiley, D., & Hilton III, J. L. (2018). Defining OER-enabled pedagogy. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 19(4).

Open Education

The use of the term ‘open’ in education means a lot of things – the movement behind Open Education itself stemmed from inequities that different institutions were finding in terms of access to learning materials for students many years ago. Some students could not afford their textbooks, so teachers began to create their own learning materials so students would all have the same experience.

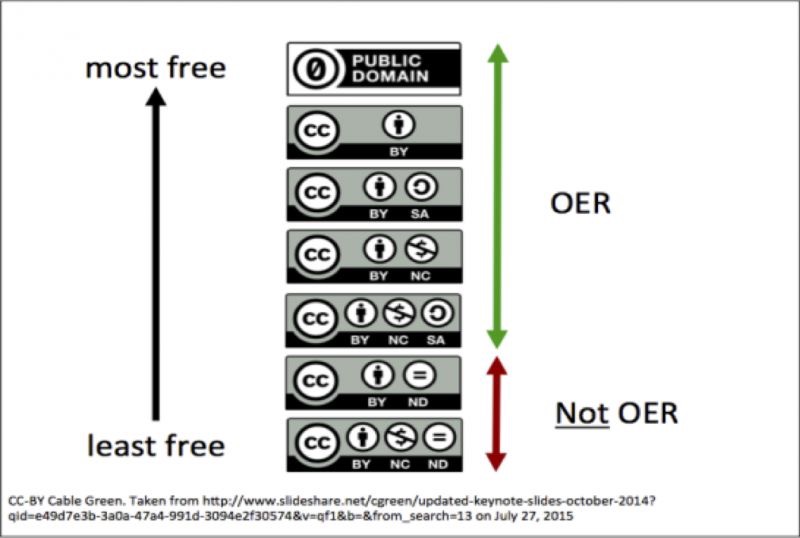

At the same time, a non-profit organisation called Creative Commons was also finding that copyright law (legislation that governed who owns what) was quite limited because it didn’t actually include provisions to allow creators to say “Hey, I want to share this”. As a result, Creative Commons created a number of licenses that creators (including educators and students) could put on their creations that allow other people to use them for various purposes and with specific ‘agreements’ regarding their use.

Once this happened, Open Educational Resources (or OERs for short) became more and more common. This eBook and website (if your scroll to the bottom) is openly licensed, meaning if you want to use it in your own teaching and learning, you can do so.

Below is a presentation that the author gave to the University of Wollongong’s Educational Developer Network group in July, 2021

Open Educational Resources (OER)

Open Education started with OERs or Open Educational Resources. These learning materials are typically created with the intention that they can be shared openly, for reuse by other educators, thus reducing the need for teachers to create their own materials again and again. OER can take the form of a journal article, a video, a diagram, infographic or even an entire unit of learning, so that other teachers and learners can benefit from the creation of others. In many contexts, especially Australia, the discussion around OER is less about the creation and sharing of OER, but simply finding and using them in teaching and learning contexts.

Open Pedagogy

Beyond OER, open education has evolved over the last 15-20 years to encompass a number of different aspects of openness, that relate to both open access, and open licensing of creations. One of the primarily pedagogical innovations in this space has come with Open Pedagogy, which refers to new ways in which students can engage with and even create open materials using the affordances of modern technologies. A common approach in Open Pedagogy is about asking students to think beyond creating for their instructors as the sole audience. These so-called “Disposable Assignments” (Wiley, 2018) are usually never seen by anyone but the instructor, but the potential for students to contribute to a knowledge base as part of their learning process is always possible. Open Pedagogies therefore usually include assignments that treat students as creators and are based on creating for and engaging with an audience in the wider world. For example, some open activities based on open pedagogy are:

- Asking students to find a Wikipedia entry on a topic related to learning, and edit that page, adding their own information, references and images.

- Work with peers in their class to write an open textbook on a topic related to the class they’re taking

- Spectacles of the Roman World Open Textbook

- Ethical Use of Educational Technology in Digital Learning Environments Open Textbook

Open Education also encompasses concepts related to freely sharing journal articles, research data, research methods, entire units of learning / classes, and other materials. See the University of British Columbia’s Open Education Toolkit for more.

As you’ll read a little more about Friere’s Critical Pedagogy Theory, Open educational practices such as the use of open blogs for reflection, can even enhance assessment practices to ensure that learners are empowered and have more agency over their own learning (Dewaard & Roberts, 2021).

If you think about it, these approaches simply mirror how people source and create knowledge in an always connected world. Writing an essay that only one person will read, then moving on to the next assignment may represent how assessment and learning activities were completed a couple of decades ago, but in a world of YouTube, TikTok, Minecraft and Wikipedia, creating an authentic experience for our students while also educating them on issues of student privacy, ownership and creative ethics, these types of practices are much more aligned with the real world.

Note that in different countries, Open Education may go by different names, and based on legislation and culture in educational settings, the advancement of this effort may be at different stages. For example, in North America, ‘Open Education’ is the general term used to talk about all aspects of openness in education, whereas in Australia this term is not heavily used, with many scholars and practioners using ‘Open Scholarship’ or ‘Open Educational Practices (OEP)’ to describe the same thing. In Europe ‘Open Research’ is the same as ‘Open Scholarship’, so be mindful of this as you’re reading journal articles and other materials from different countries.

Open Education also has interesting implications for indigenous cultures and learning, as well as power dynamics in society. Check out the below interview with Dr. Daniel Heath Justice, a professor in the Department of First Nations and Indigenous Studies at the University of British Columbia, Canada.

If you’d like to learn more, there is an open textbook called An Open Education Reader, edited by David Wiley.

Also, if you’re interested in the leadership side of education Kwatlen Polytechnic University (Canada) has openly published their Open Education Strategic Plan, led by Rajiv Jhangiani.

Gamification

When students engage in something that feels like a game during the course of their learning, this is usually referred to as ‘Gamification’, but it is more about the systematic redesign of learning experiences that lend to the improvement of learning outcomes through gamification.

Gamification or Game-based Learning has been around for many years, and can take many forms – you may have even experienced it yourself. Some teachers and researchers may separate these terms as different concepts. The Centre for Teaching Excellence at Waterloo University in Canada differentiates the concepts like this:

- Gamification is the integration of game elements like point systems, leaderboards, badges, or other elements related to games into “conventional” learning activities in order to increase engagement and motivation. For example, an online discussion forum for a Physics course might be gamified via a badge system: students might be awarded a “Ptolemy” badge after they have made 10 postings, a “Galileo” badge after 20 postings, “Kepler” after 30, “Einstein” after 40, and so on. In ideal gamified learning environments, students can see the online badges that their peers have earned to create a sense of camaraderie or competition.

- Game-based learning, in contrast, involves designing learning activities so that game characteristics and game principles inhere within the learning activities themselves. For example, in an Economics course, students might compete in a virtual stock-trading competition; in a Political Science course, students might role-play as they engage in mock negotiations involving a labour dispute.

In short, gamification applies game elements or a game framework to existing learning activities (e.g., adding points and competition elements to an online discussion); game-based learning designs learning activities that are intrinsically game-like (e.g. PowerPoint Jeopardy activities or Minecraft for Eduation lessons).

A great example was a sociology MOOC (Massive Open Online Course) ran by University of California, Irivine called Society, Science and Survival: Lessons from AMC’s The Walking Dead (This link contains horror imagery). In this free class, students essentially learned about sociology, including Maslow’s Hierarchy of needs, gender, bias, disease modelling and other topics through the lens of a popular zombie TV show.

Common approaches to gamification can include:

- Leaderboards (scores)

- Achievement of Digital Badges

- Engaging in Competition amongst your peers.

- Progression Tracking

Example Tools used in Gamification:

- Minecraft: Education Edition

- MergeCube

- Educational Robots like Ozobots, Beebots, etc.

Place-based Learning (with Mobile Learning)

The idea behind place-based learning is that we all learn in different spaces, and the idea that learning needs to happen in a classroom or in a lecture theatre and nowhere else. While many studies in place-based learning focus on the impacts of this practice on aboriginal and first-nations learners, the advantages for all learners are apparent.

By designing for and allowing students the opportunity to engage in learning experiences outside their normal learning spaces, much more rich experiences can take place.

Many good examples of place-based learning happen in the sciences, asking students to explore geology, botany, and other concepts in the real world, other experiences related to art and social sciences. These strategies, which are now increasing in use, connect students to the land and local communities where they’re growing up, and also align strongly with aboriginal and indigenous ways of learning.

As you can see from the video above, place-based learning does not necessarily require technology use – in fact its more common using this pedagogical approach to not use technology at all, so it’s important to consider that innovative pedagogies do not always involve technology, but they are still innovative.

In the case of place-education, technology can be embedded of course, and can be leveraged for distace learners especially, both to connect to other students, and also to the land where they live. As Zimmerman and Land (2014) point out, mobile technologies (with or without internet connections) can facilitate a more place-based experience for learners. While place-based education can happen without an ‘always on’ internet connection on your smartphone or tablet, this is one of the pedagogical approaches that may benefit from the use of such a device, but this also requires software on those devices to function appropriately for learning. For example, if an LMS doesn’t allow for picture uploads using a smartphone (or makes it very challenging for students to do so) this situated or place-based learning experience may not work. Additionally, if teachers want to engage in a video chat outside with their students and the students don’t have a fast mobile connection, this may also fall flat.

Please note that ‘Mobile Learning’ as a pedagogy is not simply the use of mobile technologies for learning (e.g., using a smart phone to take a quiz in an LMS), but one that takes advantages of the affordances and functionality of a mobile device to enhance learning. Any student can take a quiz anywhere, but sharing geo-tagged photos from a mountaintop when learning about alpine ecology is a completely different experience.

Virtual Field Trips

Though this pedagogical approach does require certain forms of technology, it grew in use during the COVID-19 pandemic, when many students and teachers were unable to leave their homes or travel very far. Depending on the subject matter being taught, students are now able to visit museums on the other side of the planet using Google Arts and Culture or visit national parks through 360 Video (you can drag the video below around to look around the canyon).

Being able to immerse learners into real environments they are unable to visit can give them a more authentic experience and connect real-world places and visuals to the concepts they’re learning.

Pedagogy of Care / Care-based Pedgagogy

Exploring the relationships between teachers and learners is always an interesting exercise. In some environments, the level of formality ensures that there are power dynamics that place the instructor far above the students, leaving the relationship between those in the learning environment to be primarily ‘all business’. A growing trend among researchers, especially after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic has been in Care-based Pedagogy (see Karakaya, 2021). A quick google scholar search shows that many of these studies have been published in 2020 and afterwards, in response to the changes in education that occurred because of the pandemic.

The central theme of this pedagogy is simply that educators show care for their students. This does not extend to filling the role that mental health professionals do, but has everything to do with understanding that students are humans and have lives outside of their learning experiences. As a result, pedagogies of care advocate for things like flexibility in assignment submissions, ensuring the teachers are presented as approachable and caring, and allowing students more time to engage with each other socially.

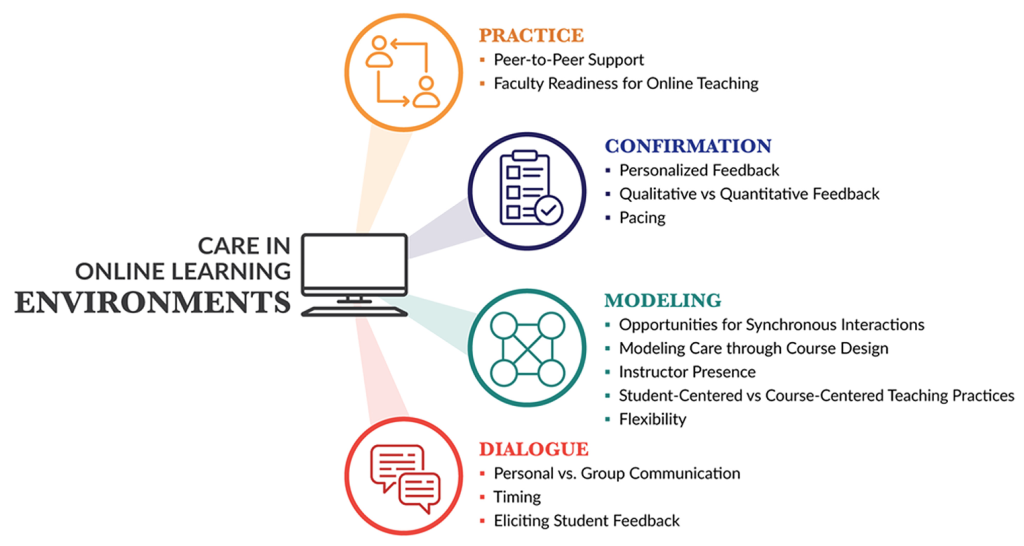

In their study, Robinson, Al-Freih and Kilgore (2020) developed the following diagram to capture key aspects of a model for online learning design, with care as a focus.

Critical Digital Pedagogy

Another trend in recent years has been on the extension of Paulo Freire’s notion of Critical Pedagogy that came out of his seminal book Pedagogy of the Oppressed. If you’re unfamiliar with this idea, essentially it relates to taking a critical stance on all education, including its structures, practices and assumptions and by considering how education may contribute to and reinforce larger societal challenges such as racism, sexism, inequity and other issues.

Critical Digital Pedagogy takes a similar stance and applies it in terms of learning technologies and how they may impact issues related to social justice. It also questions the role that teachers themselves play in being part of a ‘machine’ that allows these societal challenges to continue. Recent discussions happening in professional networks include concepts related to assessment and marking called #ungrading.

You may or may not agree with the concepts put forth in these frameworks, however they are important to consider as we learn more about how technology can impact student privacy, wellbeing and equity. If you believe that education at its core is about the social good, then this is a good area to follow

Transformational Learning

Built upon Paulo Freire’s work in Critical Pedagogy, Transformational Learning is an older idea, but very much on the forefront of how educators are thinking about the design of learning experiences. Transformational Learning its core is about changing the learner beyond the changes that may occur as a result of a traditional learning experience. Where some students may study a topic, watch some videos, read some books, and take a test, this approach sets out to facilitate a learning experience which leaves the learner changed. Whether they completely reevaluate their own understanding of a topic, reframe what they know about a topic from a different lens, or simply just learned to love a topic they hated before, this approach to designing learning experiences that can lead to societal change en masse.

Examples of transformational learning on a societal level may be the differences between how Germany and Japan teach about their wartime experience. Though controversial and largely unknown in Japan, the German school system has made a point to educate young people about their shared history, with the hopes that such events may never occur again. Similarly, the United States is now entering a period in which education of its history and the role that slavery and the treatment of Native Americans had on its expansion and the people today is now a major topic of conversation.

Maker Spaces

Though these have also been around for many years, the idea is that there is a common space where people can get together or work independently to solve problems. Community-based Maker Spaces have popped up to allow people to engage in woodworking, metalworking, 3D Printing and other areas of creation, usually charging a membership fee like a gym. In an educational setting, a Maker Space allows learners and teachers to get together to make, do and share. More than a space, it should be considered a pedagogy, born out of Papert’s Constructionism learning theory (Paper & Harel, 1991), which allows students to students create and problem solve in a shared environment, they can build upon each others’ work, be supported and scaffolded by their instructors and have meaningful learning experiences in the process (see Peppler, Halverson, Kafai, 2016). Initially implemented in libraries and extended beyond this in recent years, Maker Spaces they provide tools and spaces necessary for students to explore hands-on activities related to what they’re learning. Maker Spaces exist both in schools and universities, but may look very different.

Key Take-Aways

- Some innovative pedagogies require innovative technologies while others do not

- Open Education, Gamification, Place-based learning and Care-based Pedagogies are growing trends in education

- Many innovative pedagogies involve critical reflection on education as a whole, it’s role in society, and how students learn how to learn.

Revisit Guiding Questions

Consider the answer to the question this chapter poses. In your head, start with the phrase “Emerging Trends in Pedagogy are all about…” and see where you go. Feel free to explore more resources so you gain a deeper understanding of these ideas.

- When reflecting on the guiding questions from the start of the chapter, did what you read about change your understanding of what’s possible in teaching and learning practice? How?

- When thinking about your own experience as a student, what jumped out in this chapter that stood in contrast?

- Do you think these pedagogical approaches are beneficial to learning? Would they work in your workplace or learning context?

References

DeWaard, H., & Roberts, V. (2021). Revisioning the potential of Freire’s principles of assessment: Influences on the art of assessment in open and online learning through blogging. Distance Education, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2021.1910494

Karakaya, K. (2021). Design considerations in emergency remote teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic: A human-centered approach. Educational Technology Research and Development, 69(1), 295-299.

Leung, C. H., & Chan, Y. Y. (2003, July). Mobile learning: A new paradigm in electronic learning. In Proceedings 3rd IEEE International Conference on Advanced Technologies (pp. 76-80). IEEE.

Morris, S.M. (2017), Critical Digital Pedagogy and Design. Retrieved from https://www.seanmichaelmorris.com/critical-digital-pedagogy-and-design/ on August 9, 2021

Papert, S., & Harel, I. (1991). Situating constructionism. Constructionism, 36(2), 1-11.

Peppler, K., Halverson, E., & Kafai, Y. B. (Eds.). (2016). Makeology: Makerspaces as learning environments (Volume 1) (Vol. 1). Routledge.

Robinson, H., Al-Freih, M., & Kilgore, W. (2020). Designing with care: Towards a care-centered model for online learning design. The International Journal of Information and Learning Technology, 37(3), 99–108. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijilt-10-2019-0098

Sheridan, K., Halverson, E. R., Litts, B., Brahms, L., Jacobs-Priebe, L., & Owens, T. (2014). Learning in the making: A comparative case study of three makerspaces. Harvard Educational Review, 84(4), 505-531.

Smith, G. A. (2002). Place-based education: Learning to be where we are. Phi delta kappan, 83(8), 584-594.

Zimmerman, H. T., & Land, S. M. (2014). Facilitating place-based learning in outdoor informal environments with mobile computers. TechTrends, 58(1), 77-83.

Further Reading

Freire, P. (1975). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Penguin Education.

Gamification (ETEC510 course Wiki – UBC)

Gamification and game-based learning. Centre for Teaching Excellence, University of Waterloo. (also has great guidance on these approaches in practice)

Morris, S. M., & Stommel, J. (2018). An urgency of teachers: The work of critical digital pedagogy. Hybrid Pedagogy.

Place-Based Education: The STAR 3-to-3rd Model (12:14). Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VtyWvODdv9E

Did this chapter help you learn?

100% of 14 voters found this helpful.