How can we empower learners through pedagogy?

Overview

In this chapter we’ll look at different approaches to designing technology-enabled and online learning experiences that support access, inclusion and equity. While the most common mindset in ways to think about digital learning and access are to go the purely technical route, this chapter will focus primarily on pedagogical approaches, or ways to think about teaching practice.

Learning Outcomes

- Understand basic theoretical underpinnings of Universal Design for Learning (UDL)

- Consider how to apply UDL in your learning context

- Understand how basics of user-interaction design (or Learning Interface design) and how it can support our projects.

- Understand how open education and access relates to equity

- Understand the difference between Differentiation and UDL

- Explore how Indigenous ways of knowing and learning can be incorporated into your learning designs.

Why is this important?

Universal Design for Learning (UDL) is an incredibly widespread teaching approach that aims to ensure all learners can learn in ways that works universally, with as few barriers as possible. This practice is important to understand because it goes beyond responding to existing barriers, to the goal of ensuring that barriers don’t exist in the first place.

Guiding Questions

As you’re reading through these materials, please consider the following questions, and take notes to ensure you understand their answers as you go.

- What can we do to create learning experiences that are accessible by all learners?

- What non-technical considerations should we make to do this work?

- Should all activities and assessments be standardised or personalised? What effect does this have on learning?

Key Readings

Rose, D. (2000). Universal design for learning. Journal of Special Education Technology, 15(3), 45-49.

Smith, F. G. (2012). Analyzing a college course that adheres to the Universal Design for Learning (UDL) framework. Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 31-61.

Empowering through Pedagogy

In the last chapter we touched on the idea of being reactive or proactive to the needs of our learners. While there are some barriers that we may need to be reactive to, that is responding to the barriers after they have been identified, one important teaching and curriculum development strategy is to anticipate barriers and design instruction and materials so that barriers are reduced before they even exist. To this end, there are a number of frameworks and ways to think about pedagogy that can set all students up for success.

Universal Design for Learning (UDL)

Accessibility is primarily geared towards supporting consumers of media that are physically or neurologically diverse and to ensure everyone has equal access to materials.

UDL, on the other hand is an approach to designing media to support access for all consumers of media regardless of their abilities in a proactive manner, as opposed to reactive is at the heart of UDL.

Developed by Rose and Meyer (Rose, 2010; Rose & Mayer, 2000, 2002) as an extension of universal design for physical spaces. When we consider the designs of buildings, parks and other environments, these need to be designed such that all users can access them to use them effectively. For example, a ramp or button to open a door is not just usable by those with motor challenges, but can benefit all visitors. The same is true for learning experiences, so when we think about creating materials, or figuring out what our learners are going to experience and create, we can consider how we can ensure that all learners can benefit, regardless of ability.

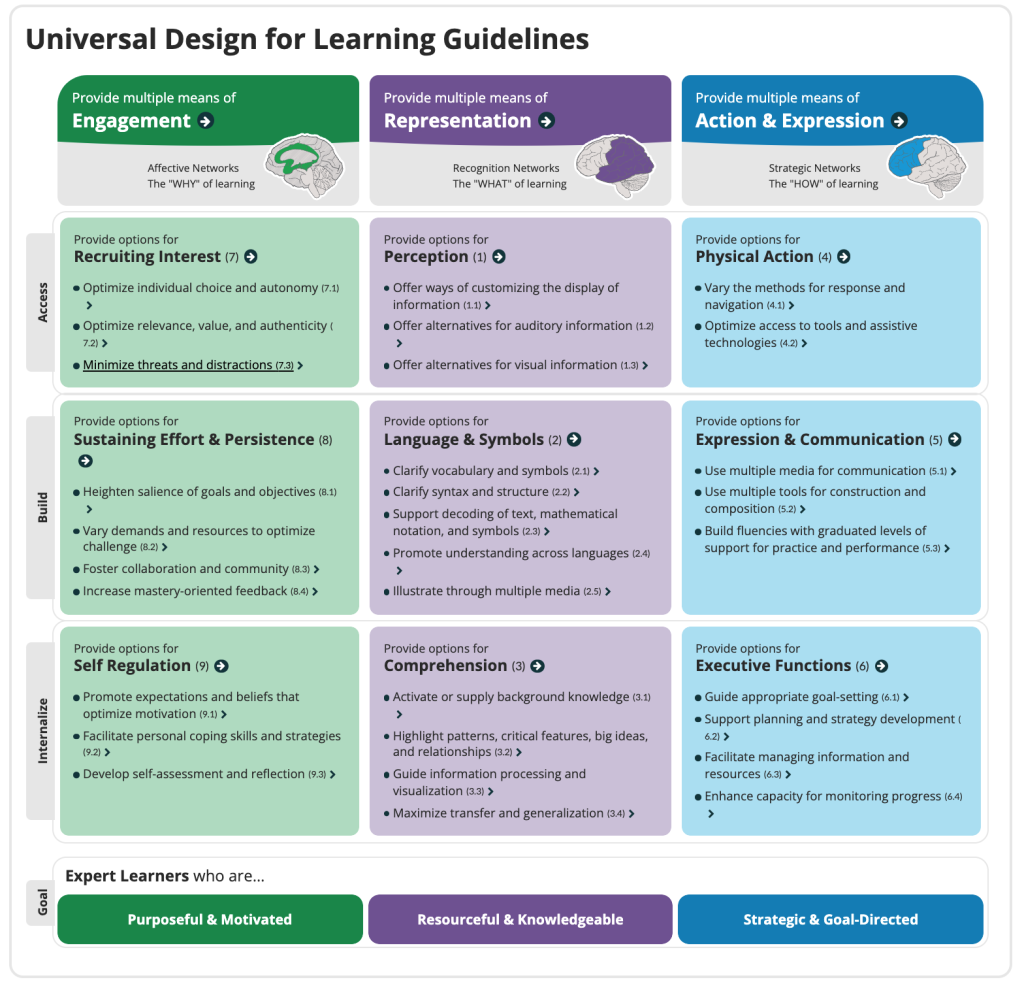

UDL at its’ core is less about the hands-on creation of materials to ensure they’re accessible, but considering how we can present information, provide opportunities for learning, and engage students through providing multiple means of :

- Representation

- Engagement

- Action & Expression

As you can see in the infographic below, the choices we make as teachers and designers of learning experiences have much more to do with pedagogical choices than technical ones. Choosing to add a diagram to a text-based explanation of the weather cycle, for example, is one non-technical choice that can support and enhance learning, while allow students variation in how they demonstrate learning is another.

Critiques of UDL as an evidence-based framework

While there are many supporters of UDL, Boyson (2021) presents a critique of it that echos many discussions around that of Learning Styles. Given that there is no evidence to support that teaching to an individual’s learning style actually improves their learning, the critique around UDL is the same based upon the interpretation that ‘if we do this, learners benefit’, when there may not be that much evidence to support this. Ok et al. (2017) conducted a review of 13 studies that featured UDL-based interventions and found mixed results – UDL interventions varied a lot across the studies, with researchers reporting in varying ways how they applied the interventions and what the interventions actually did. While this doesn’t provide a concrete answer to UDL’s efficacy either way, the authors do note that “UDL-based instructional practices provide flexibility and scaffolds that promote access to the general education curriculum and support achievement on academic outcomes.” (p.136).

For now, instead of considering UDL practices a ‘must’ that will definitely provide learning gains for our students, we may just think about UDL as a framework of practices intended to support learners regardless of individual differences in ability or current life circumstances.

Alternatives & Options

UDL at its core is all about providing alternatives and options both to established ways of teaching and learning, but also to how we engage and assess our learners. While it’s usually an easy task to add a video to our learning materials to support further understanding of a complicated concept, or to create an audio version of reading materials, motivating students and assessing them can be a different story.

Assignment Choice is a commonly used UDL strategy, which allows students different choices for how they approach and / or create their assessment work.

Check out the Open Pedagogy section of chapter What are the Emerging Practices in Pedagogy? – this notion of Open Pedagogy ties into UDL’s multiple means of action and expression.

Step outside the Box

Another way we can think about this is to reframe the benefits of certain reactive practices to a proactive practice that is beneficial not just to those with disabilities, but for all students. For example, organisations may hire workers to sit in class and take notes for a single learner that has motor differences. One step is to simply share these notes with the entire class. Another option is to remove this note-taker and have all students share their notes with each other. Another option further still is to have the instructor provide notes, then allow all students to annotative them in a shared and collaborative manner.

For an overview of different strategies and examples of UDL in practice, check out the video below. Additionally, Smith’s research (2012) provides insights into how teachers who engage in UDL work can think about reframing their existing practices and increase reflective practice through the use of technology.

Also check out Universal Design 4 Learning, a site created by an excellent UDL and Open Education educator and advocate, Helen DeWaard.

What about Differentiation?

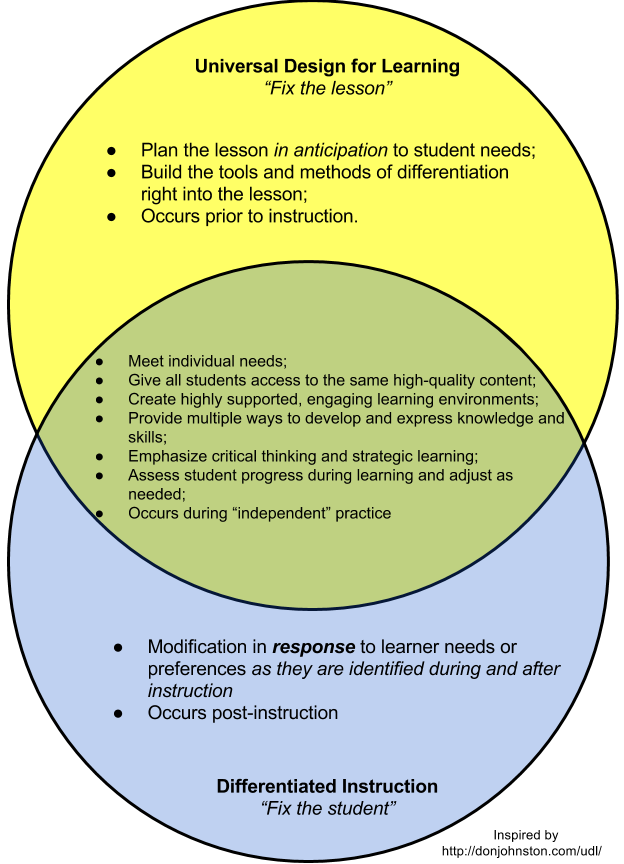

While UDL aims to ensure that all learners have equal access to learning, including opportunities to demonstrate it and access it, differentiation is all about teaching based on individual student characteristics, including their readiness, interests, and learning profiles / preferences. According to the NSW Dept of Education, differentiation is all about creating a flexible learning environment that allows all learners to progress and learn effectively, regardless of who they are, while also building in choice.

While UDL and differentiation overlap in many ways, differentiation occurs as a process, while UDL is more often preplanned in its implementation to reduce barriers before they can manifest. Also consider this diagram – do you agree that these are about ‘fixing’ lessons and students, or is it more about meeting student needs through different lenses?

Modality

When considering design-based choices for increasing access to learning experiences, we can think about modality as one such means to reduce barriers – that is where the learning is physically happening. Is it happening 100% face to face, 100% online, or a mix of both in a Hybrid / Blended / Flipped model or a Hyflex learning model? For more on different modalities and what they look like, check out the chapter How do we Learn with Technology?

Empowering Through Design and Usability

More often than not, finding ways to reduce barriers in our designs can be informed by research. A couple of areas of research frame this reduction of barriers in terms of human memory and cognition.

Mayer’s Cognitive Theory of Multimedia Learning and all its associated principles focus specifically on how learning can be made more efficient and effective through specific design choices for multimedia materials (including text and images).

Cognitive Load Theory (Sweller et al., 2011) is a related area of research that is based upon the limited working memory capacity of the human brain. If we can design materials and activities that reduce the allocation of cognitive resources to information that isn’t relevant to learning itself, then learning can be enhanced.

Check out more on these theories (including references to research) in the chapters What is the Process for Designing an Experience? and How to we Learn with Technology?

When it comes to Interaction Design (or IxD), this is a whole other area. While it may not be pedagogical in nature Usability refers simply to how usable something is, and this is related to how learning materials, and learning experiences themselves are designed, including everything from the visual design of an LMS (Learning Management System) like Moodle, Canvas, Google Classroom, etc., the structure and hierarchy that that learning materials are organised in, the technologies we use and even where buttons are located. Meiselwitz and Sadera (2008) found a correlation between student perception of usability and learning outcomes in an online environment, suggesting that how an online experience is designed, can actually affect marks, and student success.

A number of studies have also explored the relationship between the aesthetic design of online learning systems, and how students perceive their usability and credibility as a result (David & Glore, 2010; Yousef et al., 2015; Zaharias & Poylymenakou, 2009). In other words, it could be that the more well designed a technology-enabled learning experience is, there more credible is seems to students and potentially the more supportive it is of learning.

Check out the first half of this first lecture from an Interaction Design class, where this author speaks about how design can make an experience simple and intuitive for users (and learners). The next video (if you’re interested) covers how cognitive and evolutionary psychology can play a role in the design of digital interfaces.

Adapting Indigenous Ways of Learning with Technology

As we work to decolonise education – that is to acknowledge and work to dismantle structures that disenfranchise learners due to the historical and contemporary effects of colonisation, understanding indigenous worldviews and ways of learning is an important practice to undertake. If you need a refresher on Aboriginal ways of learning and how they related to learning theory check out How do we Learn with Technology? for more.

Most indigenous pedagogies are centred around connection to others and to country. How knowledge is shared, approached and respected can be quite different than western notions of education and learning, so it’s important that we are responsive to these differences and can embed ways of knowing, learning and being while we use technology.

Reedy (2019) suggest 6 methods online instructors can use to support Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students including:

- Ensure students can make personal connections online

- Allow indigenous students to safely identify each other to facilitate connection

- Design learning activities that promote cross-cultural interactions and shared understanding through different perspectives and cultural lenses

- Ensure teacher presence is strong with culturally and pedagogically appropriate supports

- include Indigenous perspectives in learning materials

- Ensure learning materials and activities are accessible in both format and completion

If we have a look at the First Peoples’ Principles of Learning from the Canadian context, consider how universal they might be for all learners. The Principles are as follows:

- Learning ultimately supports the well-being of the self, the family, the community, the land, the spirits, and the ancestors.

- Learning is holistic, reflexive, reflective, experiential, and relational (focused on connectedness, on reciprocal relationships, and a sense of place).

- Learning involves recognising the consequences of one‘s actions.

- Learning involves generational roles and responsibilities.

- Learning recognises the role of Indigenous knowledge.

- Learning is embedded in memory, history, and story.

- Learning involves patience and time.

- Learning requires exploration of one‘s identity.

- Learning involves recognising that some knowledge is sacred and only shared with permission and/or in certain situations.

Adapting principles around connection to self, family, community and country is definitely possible within online and digitally-enabled learning experience. How we do this is quite simple and may include the following strategies among others:

- include videos of community members and elders in learning materials

- ensure that indigenous perspectives are included in learning materials, regardless of domain

- make learning activities and assessments culturally relevant – even better if they can link to country

- demonstrate respect for and elevate the voices of indigenous scholars and students alike.

Key Take-Aways

- Universal Design for Learning provides an interesting framework to think about removing barriers before they may negatively impact learning.

- Other pedagogical approaches and models, such as Open Pedagogies and Mayer’s Theory of Multimedia learning can support the reduction of barriers and support UDL principles.

Revisit Guiding Questions

Now that you’ve learned a little about UDL and the proactive actions we can take as educators to increase access and remove barriers before they present themselves, have a think about what you already do in this space, and what you can do differently in the future? Are their barriers to you engaging in UDL work? What are they?

Conclusion / Next Steps

Now that we’ve learned about some non-technical ways to support student learning and reduce barriers either using technology or not, the next chapter will focus more on the technical aspects of reducing barriers, specifically around Web Accessibility and the use of specific technologies to support the control of computers and the creativity of students.

References

Boysen, G. A. (2021). Lessons (not) learned: The troubling similarities between learning styles and universal design for learning. Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Psychology.

David, A., & Glore, P. (2010). The impact of design and aesthetics on usability, credibility, and learning in an online environment. Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration, 13(4).

Meiselwitz, G., & Sadera, W. (2008). Investigating the connection between usability and learning outcomes in online learning environments. Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, 4(2), 9.

Ok, M. W., Rao, K., Bryant, B. R., & McDougall, D. (2017). Universal design for learning in pre-k to grade 12 classrooms: A systematic review of research. Exceptionality, 25(2), 116-138.

Reedy, A. K. (2019). Rethinking online learning design to enhance the experiences of Indigenous higher education students. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 35(6), 132–149. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.5561

Rose, D., & Meyer, A. (2000). The Future Is in the Margins: The Role of Technology and Disability in Educational Reform.

Rose, D. H., & Meyer, A. (2002). Teaching every student in the digital age: Universal design for learning. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development, 1703 N. Beauregard St., Alexandria, VA 22311-1714

Sweller, J., Ayres, P., & Kalyuga, S. (2011). Cognitive Load Theory (Vol. 1). Springer Science & Business Media.

Yousef, A. M. F., Chatti, M. A., Schroeder, U., & Wosnitza, M. (2015). A usability evaluation of a blended MOOC environment: An experimental case study. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 16(2).

Zaharias, P., & Poylymenakou, A. (2009). Developing a usability evaluation method for e-learning applications: Beyond functional usability. Intl. Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, 25(1), 75-98.

Further Reading

McGuire, J.M., Scott, S.S., & Shaw, S.F. (2006). Universal Design and its Application in Education, Journal of Remedial and Special Education, 27(3), 166-175.

Rose, D.H., Harbour, W.S., Johnston, C.S., Daley, S.G., & Abarbanell, L. (2006). UDL in Postsecondary Education: Reflections on Principles and their Application, Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 19(2), 135-151.

Tomlinson, C. A. (2014). The differentiated classroom: Responding to the needs of all learners. Ascd.

Best Practices through UDL: Colorado State University (Video: 13mins)

UDL Guidlines (CAST)

Universal Design of Instruction (UDI): Definition, Principles, Guidelines, and Examples (UW Do-IT)

https://www.acara.edu.au/curriculum/student-diversity

BCCampus Indigenisation Guides for teachers, researchers and other roles (from a Canadian Perspective)

First Nations Education Steering Committee (2007). Retrieved from http://www.fnesc.ca/first-peoples-principles-of-learning/

Did this chapter help you learn?

No one has voted on this resource yet.

Provide Feedback on this Chapter