Advanced Models of Learning and Curriculum Design

Overview

In this chapter we’re going to be looking at different models of learning and curriculum design, that can apply in different fields as well as at different levels within an organisation.

To reorient yourself with the topic, feel free to take a look at the What is Learning Experience Design? chapter in the book Introduction to Learning Technology as this will provide a foundation for models of learning design practice for various contexts. This chapter will not go into the basics of things like backwards design or ADDIE, so feel free to go back and read about those topics before you get started here.

Why is this important?

To take the design of your learning experiences to the next level, its important to have a good understanding of the different models of learning design and ways of the thinking about the work that you do. While using established models that have been around for 50+ years might work for most, exploring different ways to think about teaching and learning can help you to innovate and reconceptualise your designs.

Guiding Questions

As you’re reading through these materials, please consider the following questions, and take notes to ensure you understand their answers as you go.

- Beyond basic models of instructional design (e.g., backwards design, ADDIE) how do you approach the development of a lesson?

- What is the relationship between all the different moving pieces of a lesson you’ve worked on?

- As a student, what insights do you have on why you’re asked to complete specific tasks or engage with specific learning materials?

Key Readings

Biggs, J. (2014). Constructive alignment in university teaching. HERDSA Review of Higher Education, 1, 5-22.

Trigwell, K., & Prosser, M. (2014). Qualitative variation in constructive alignment in curriculum design. Higher Education, 67(2), 141-154.

The Nature of Designing Learning Experiences

Before we begin, it’s useful to stop and think for a second. To think about what we believe about teaching and learning – what they mean and how we want to be a part of them. A term used a lot in research spheres is ‘Ontology’, or the way we think about the nature of something (such as reality). There is no right answer here and everyone seems to have a different ontological approach when it comes to teaching and learning but there are a few different approaches to what teaching actually is, and by extension what the learning experience becomes.

- Teaching is the delivery of information into the mind of the learner

- Teaching is the enactment of teaching practices

- Teaching is the facilitation of learning

Your beliefs about teaching and learning may be a single one of the above, or a combination of them all – there’s no right or wrong answer – but our beliefs about the role of teacher and learner is usually the foundation of how we approach the work at a foundational level.

Revisiting Bloom’s Taxonomy

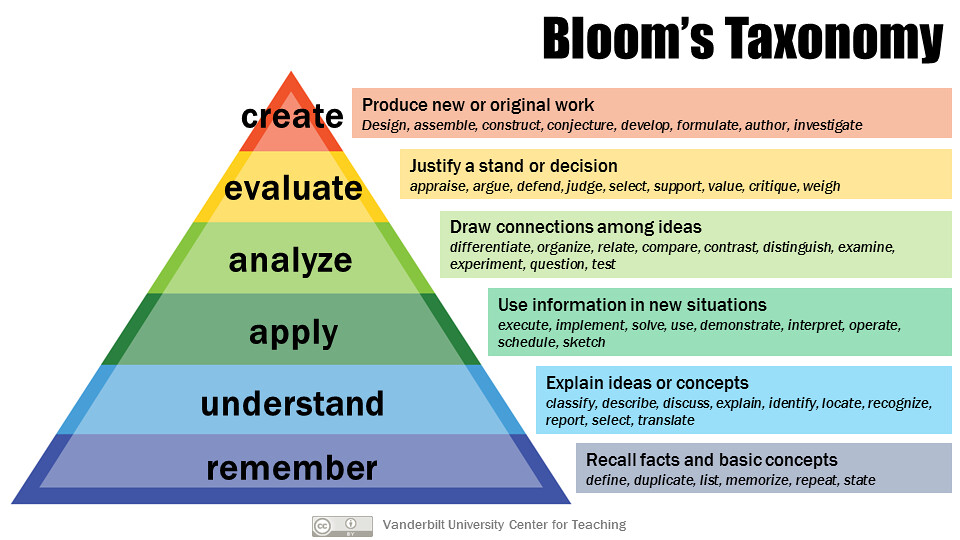

If you’ve never heard of Bloom and his Taxonomy and you’ve been working in the education sector within the last 50 years, that’s pretty amazing. Just to recap, in 1956 an educational researcher named Bloom came up with a taxonomy (categorisation) of different skills that students need in order to become proficient in any given topic and different levels, the taxonomy focused on different domains of learning, which are often categorised and represented as hierarchical.

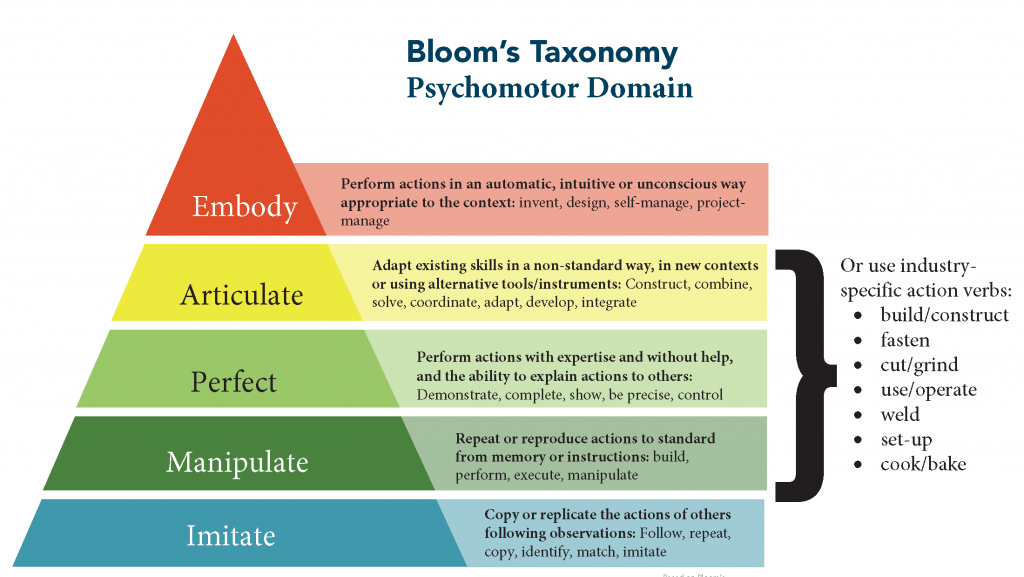

Interestingly, he developed taxonomies for 3 different domains – cognitive, affective, and psychomotor, though the cognitive taxonomy is the one almost everyone knows about, because it has informed the development of written learning objectives for over 60 years, possibly because they provide verbs you can use when writing them.

It should be noted that over the years, some critiques of the cognitive domain taxonomy have been presented, including a good discussion by Furst (1981). In most of these critiques, it’s not really about the taxonomy itself, but how it is presented to teachers and inferred recommendations for application. Specifically reflecting on our own ontological view of teaching and learning there are multiple ways we can interpret the diagram below. On one hand, we can interpret this taxonomy as its often visually presented – sequential and hierarchical (e.g., students need to first remember, before they understand, etc.), or we can look at this pyramid critically and interpret it in another way. For example, in the act of creation and exploring, we can come to understand something better, and afterwards retain new ideas and knowledge based on this experience. Thus the sequential and hierarchical structure may not be the only way to interpret the taxonomy, and this interpretation may, in fact present constraints in how we design and deliver our learning experiences.

The with the rise of care-based pedagogy and more human-centred learning design approaches, the affective (or more emotional) domain is definitely worth revisiting.

Finally, the psychomotor domain – that is, the skills and physical abilities need to complete a task or learn something new – is definitely useful when we consider how many students learn. The more we learn through research how learning is more than just a cognitive process, the more these these oft-forgotten second and third domains make sense.

The following video outlines a how Bloom’s Taxonomy in the cognitive domain can be applied to the use of digital tools. What do you think? Is it valid? Is it appropriate to call it ‘Bloom’s Digital Taxonomy’?

A Hierarchical Practice

When we think about the practices of designing learning experiences from an outcomes-based perspective, we usually think in terms of a class – a contained learning experience that we are intimately involved in, either teaching outselves or designing in concert with colleagues. But how does this learning experiences fit into a larger whole? How do we design learning experiences knowing they often feed into a larger collection of learning experiences that build upon each other and are interrelated? Perhaps we don’t 😂

In many educational institutions, this level of planning and organisation may not happen, with individual instructors planning lessons and teaching in complete isolation from each other, never talking about how their classes or learning experiences related to each other at all.

In other workplaces this work is collaborative and integrated across units for development and ‘cross-polination’ of ideas. When we think of designing learning experiences that are trans-disciplinary – those that span across multiple subject areas to integrate and consolidate knowledge for different applications (e.g., Maths combined with literacy, etc.) these practices require collaboration. In the private sector and in many higher / tertiary education settings, the learning designers are not the subject matter experts (fondly referred to as ‘SMEs’), so those with expertise in learning design and curriculum development usually work closely with experts in the field who are more often than not the people who will be teaching the class being designed.

An Aligned Curriculum

Building upon the concept of Backwards Design, the idea that our learning outcomes (AKA objectives, AKA goals) form the basis of all our planning and design work as educators is a foundational concept. But how we go about this work varies from individual to individual

As Biggs notes, “knowledge is constructed by the activities of the learner” (Biggs, 2014, p. 9) which may be in contrast to other approaches as direct instruction and content transfer. “Learning takes place through the active behavior of the student: it is what he does that he learns, not what the teacher does.” (Tyler, 1949). Do you agree with this statement? While it is true that learning itself depends on what the student does, the teacher is instrumental in designing and planning the learning experiences for the students, so what the teacher does is incredibly important, but the meaning is taken.

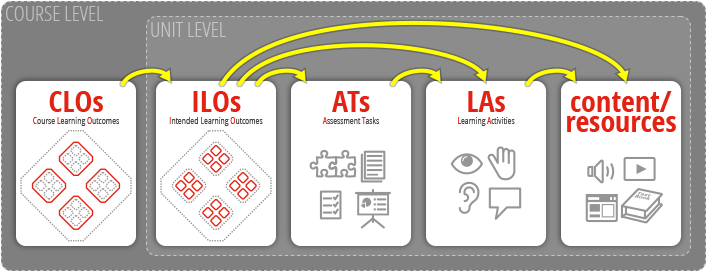

Based on this paradigm, constructive alignment links what students do and what they engage with, directly with the intended learning outcomes for any given lesson or learning experiences.

This is why writing good learning objectives is very important. While some educators feign the use of learning objectives for many reasons, and may completely disagree with either how they are used and what they mean in a more philosophical sense, much of Instructional Design and Learning Design Practice is based on their ability to create a foundational role in a designed learning experiences – the spine in the skeleton so to speak.

John Biggs, an educational researcher and pscyhologist outlined constructive alignment over 30 years ago. In a nutshell, this framework is a more systematic and actionable version of backwards design and goes as follows:

- Identify Intended Learning Outcomes (ILOs)

- Design Assignments / Assessments that measure learner ability to master ILOs

- Design and Develop formative Learning Activities that allow students to learn the skills, knowledge and abilities to complete assignments successfully

- Choose, Curate or develop content and resources (AKA learning materials) that support students ability to get the most out of the Learning Activities.

In contrast to some more traditional models of instruction (e.g., “Here’s the textbook. There are two exams. Done”), that focus on an instructor-centred, content first model, Constructive Alignment provides a framework to engage learners in many different levels of the learning experience, but most of all it assumes that learning is not simply the creation of an artefact based on content consumed – it is a process that requires engagement, building of understanding and demonstration that learning has occurred.

If you’re having trouble understanding this model, it’s helpful to think about it as a cascading waterfall:

- Once we’ve written our Learning Objectives, we can formulate a way that students provide evidence that they’ve mastered them, meaning we design a Summative Assessment.

- Based on what this/these Summative Assessments looks like, we can come up with Learning Activities and that can help students process new ideas and complete practice versions (Formative Assessments) of the assessment (and perhaps fail) at completing the it, before they submit the final version. In other words, the Leaning Activities are in place to support successful completion of the Summative Assessments.

- In order to get the most out of these Learning Activities, students should be given Learning Materials (content and resources) that give them the knowledge, skills and abilities to be able to participate in these activities.

When examining existing learning experiences through this lens, we can then ask ‘What purpose does X serve in supporting learning objectives?’ It may be that we find students are reading a book chapter that contains information they’re never assessed on, or they’re engaging in a learning activity that has nothing to do with an assignment. These elements of a learning design can then be considered extraneous or ‘orphaned’ because they serve no purpose in the scope of the learning experience, so can then be refactored or even removed.

While definitely a useful model, evidence to support its improvement of learning isn’t so prevalent (see key reading above), so we must be mindful that the positive impact on learning that this model assumes based on its very existence very much depends on how it is implemented in practice. If learning objectives are not written in a way that allows learner exploration, if learning materials don’t support activities, etc etc, constructive alignment could have the potential to corral learners along a set path, not allowing them to see the forest for the trees.

Taken together, we need to be mindful that the frameworks and models we may read about simply provide a way for us to think about a topic, and may not provide a universal solution to creating the perfect learning experience for our students.

SOLO (Structure of the Observed Learning Outcome)

Biggs has been busy – he also developed something called the SOLO Taxonomy, which is a way of classifying learning objectives based on what level students are at in their learning. If you look at the higher levels of the taxonomy related to ‘Relational’ and ‘Extended Abstract’, these levels align somewhat with the notion of schemas and connections to previously learned knowledge, skills and abilities that form the foundation of instructional strategies (check out the section on schemas in How do we Learn with Technology?)

And Many More…

With both Constructive Alignment and the SOLO taxonomy presented, be aware that there are many, perhaps hundreds of learning design frameworks in practice. Again feel free to check out the chapter What is Learning Experience Design (LxD)?, another great resource is the padlet below, created by Danielle Hinton (@dintondm), sourced from other Twitter users.

Curriculum Mapping

In a broader context, any collection of learning experiences or classes usually forms a larger hole, and educators have worked for years using models of Curriculum Renewal to inform implement changes. Much like Instructional Design models, the approaches are similar, including a needs analyses, backwards design / constructive alignment and redevelopment of learning materials.

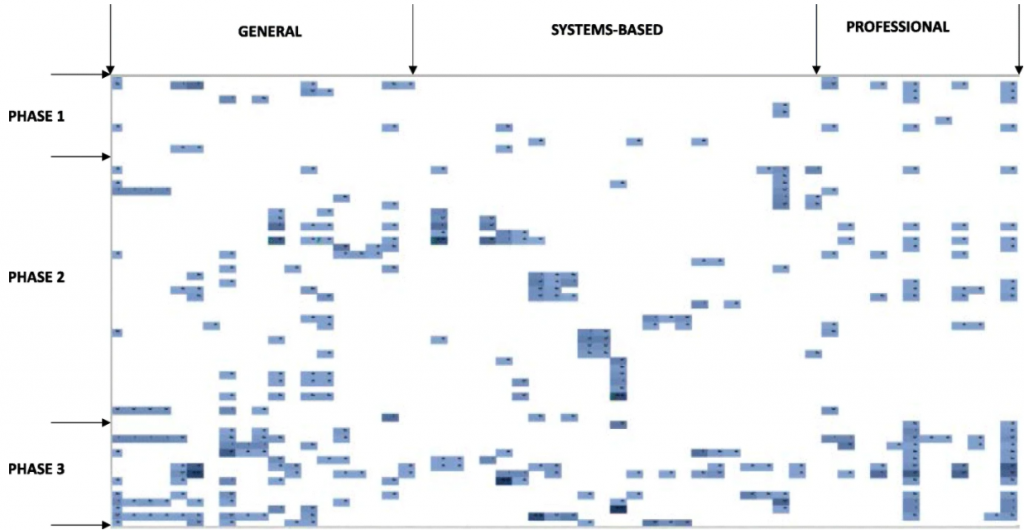

This level of design can include a broader application of alignment in terms of student progression and the different levels at which they can achieve ILOs. Most degree-level designs will include Program or Course Learning Objectives (PLOs / CLOs), with terminology differing based on region. From here, learning designers and administrators can then align ILO’s with these PLOs’ to articulate how learners may progress.

The University in Toronto (Canada) has fantastic resources that provide a window into how this large university engages in this work. This model, in use my many other institutions around the world relies on ‘mapping’ student progression in the form of levels of attainment.

Here’s how it goes – When a student first starts out, it is very unlikely they’ll be able to master a PLO during their first class. Even a year into their program or degree, they may not be able to master it, but by the end they should be able to. This progression is articulated on a table that maps their progression by using 3 levels:

- Introduced: The objective is introduced with assignments, activities and content addressing it in a basic level

- Developing: The objective is reinforced, focusing on further development of students’ knowldge skills and abilities related to their application of this objective.

- Proficient: Students demonstrate their proficiency and master of this PLO

Curriculum mapping can even be done for indigenising curriculum to ensure cultural competencies are being met or cultural knowledge is embedded in the curriculum. The University of Queensland has a good report that shows a couple of examples on this.

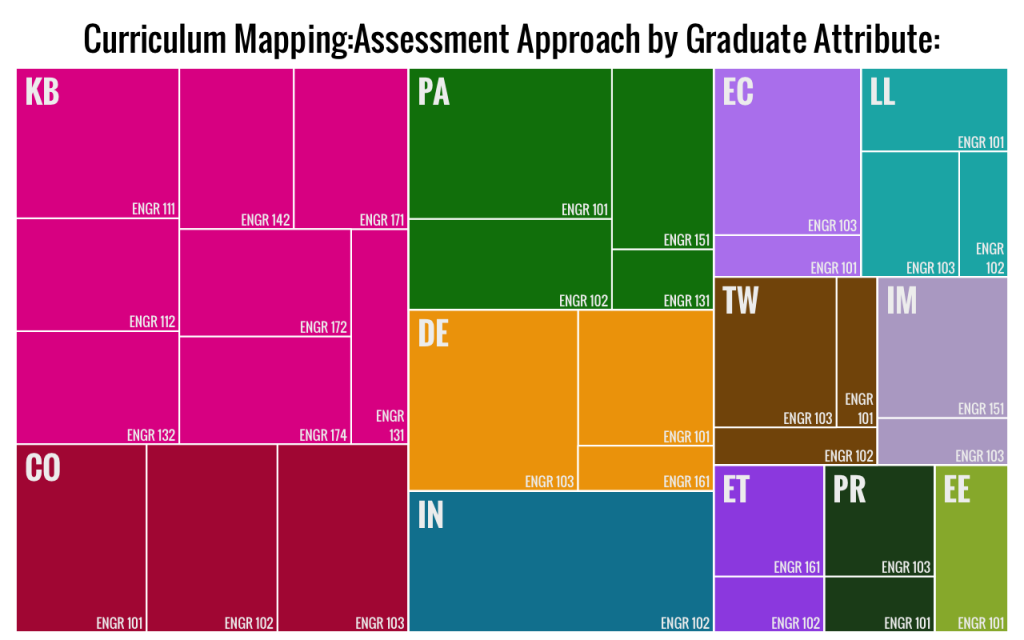

The example provided below is part of a brainstorming exercise conducted in early 2021 for classes offered at the University of New England, Australia (they don’t represent final designs or alignment)

Course Learning Objectives (CLO)

- CLO1: Explore and evaluate the design of technology-enhanced learning experiences in a variety of delivery methods / modalities

- CLO2: Design and lead effective technology-enhanced learning experiences in modalities suited to your teaching and learning context

- CLO3: Advocate for all learners to ensure inclusion, representation, equity and access in technology-enhanced learning experiences

- CLO4: Teach others and provide leadership in areas related to emerging trends and issues within the field of educational technology (include considerations in emerging trends)

| CLO1 | CLO2 | CLO3 | CLO4 | |

| EDIT426: Introduction to Learning with Educational Technology | I | I | I | I |

| EDIT415: Leadership in Educational Technology | P | P | D | I |

| EDIT425: Emerging Pedagogies and Practices in Educational Technology | D | P | D | P |

| EDIT513: Educational Technology for Access and Inclusion | D | D | P | D |

| EDIT517: Developing Learning Communities in Online Spaces | I | P | D | D |

| EDIT518: Introduction to Learning Analytics | I | D | I | P |

| EDIT521: Designing Effective Learning Experiences with Technology | P | I | P | P |

Standards Mapping

In schools, professional and military contexts, these PLOs may not exist, but have already been established by governmental departments of education, professional bodies or military administration based on the competencies and abilities that learners need to demonstrate. In these workplaces and learning contexts, similar processes in the design of curriculum usually take place, though this work maybe completed at a higher level than those engaged in direct teaching and learning.

Examples of standards include:

- NSW Education Standards Authority (NESA) Professional Experience Framework that all new teachers need to be assessed against to become teachers in New South Wales, Australia.

- The Australian Joint Professional Military Education Continuum

Visualisation

Curriculum maps can also be visualized in many ways. See examples below.

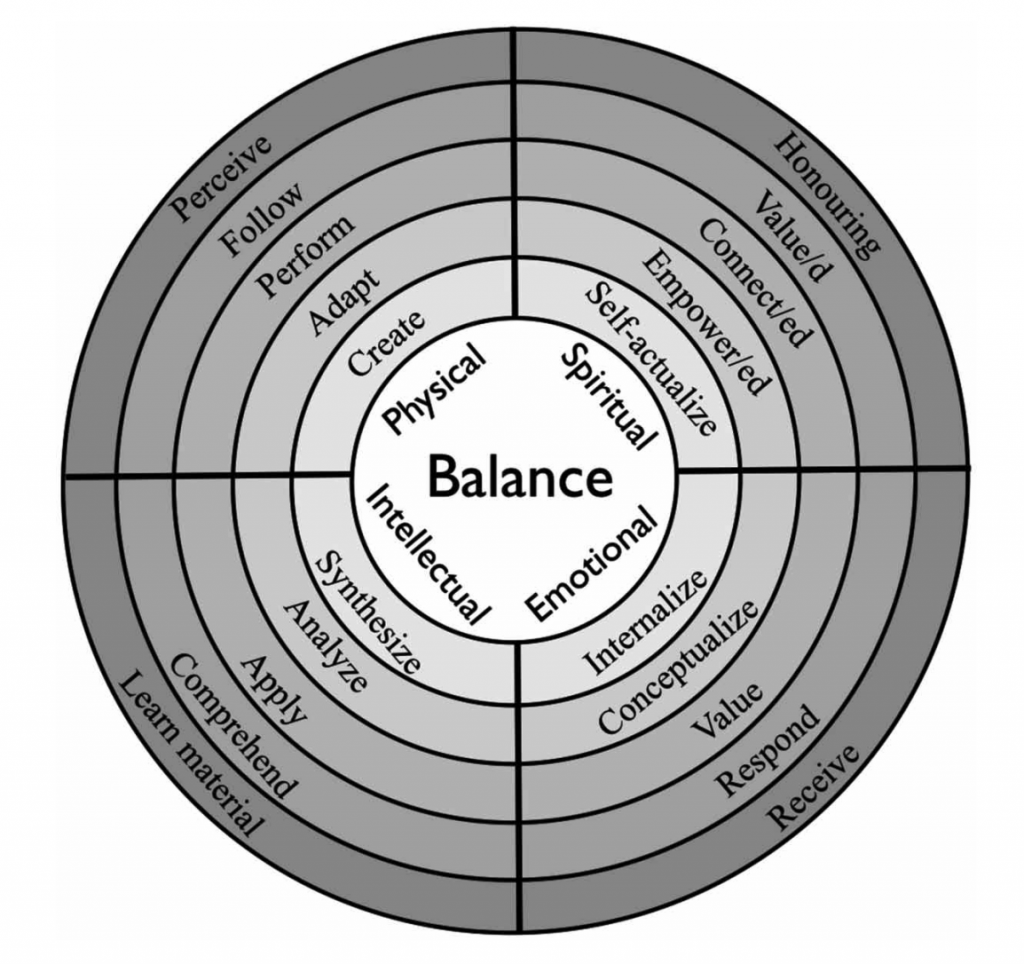

Indigenous Frameworks

Along with the 4 R’s and the 8 ways mentioned in How do we Learn with Technology?, LaFever (2017) also outlined a framework based on the Medicine Wheel, a traditional motif if Native American and First Nations cultures. This framwork looks quite similar in approach to the hierarchical structures of Bloom’s above, so looking from the outside – in, we can approach the design of learning experiences from different perspectives and intentions, catering what we are teaching, exposing learners to, and asking them to do in different levels and different lenses. Note that the author intends the words included in this framework to inform the creation of Learning Outcomes / Objectives as well.

Non-formal Frameworks

While we do have lots of academic literature on models and frameworks and theoretical frameworks and integrated models…it can get a bit tiring. There are, however other ways to do this work that may not be articulated in the research. Many educators may not have been exposed to these more formal models of design, but they still are able to create great learning experiences for their students.

On the instructor-centred side of things, many instructors think of this process as a journey, and use multiple methods like mind-mapping, outlining and others to create a story of what their students will do and experiences along this narrative. Should a learning experience be linear or nonlinear? Should it be rigorously outlined or all about free exploration?

From the student-centred side of things, some educators co-design their classes as they go, responding fully to the needs and interests of the students and allowing them to source and control the learning materials and assignments they engage with.

There are so many different approaches to designing and developing learning experiences that it’s impossible to document. Most educators are informed by their own understanding of the nature of learning and teaching, so whatever research and practices they’re interested in, or the subject matter they are teaching will guide how they plan. Perspectives from different cultures, such as those from Aboriginal, Indigenous and First Nations ways of knowing and learning can be a part of your pedagogy, or weaving in Socratic questioning or case analysis. All of these are valid ways to think about teaching and learning, while also allowing for diversity of experience within a student’s journey.

A Critical Stance

While everything covered in this chapter seems to provide us with systematic processes and tools to be able to design effective learning experiences, some educators perceive these methods as potentially limiting the capacity of students to only achieve what is outlined for them by instructional designers or teachers, essentially relegating them to ‘cogs in a machine’. An emerging field in instructional design (which is more of a discussion and philosophical stance at the time of writing) is called Critical Instructional Design (related to Critical Digital Pedagogy)

When considering this framework, established models and practices within education are framed through more of a social justice framework, questions whether practices related to assessment, curriculum design and even models of learning may simply reinforce societal inequalities and reinforce inequity and bias.

When engaging in Critical Instructional Design, we can assume that all bets are off as far as systematic means of design, but how we interpret this epistimilogical approach to teaching and learning is ultimately up to us. What if we could do away with grading / marking? What if we wanted students to create their own learning materials instead of being given them? Critical Pedagogies and Instructional Design methods serve a really important purpose, because they get us thinking critically about our work and the role that it plays in broader contexts and can help us to think outside of the box in terms of established norms in practice.

Key Take-Aways

- Instructional and Learning Design models, frameworks and practices can apply at all levels of instruction from institutional Level, all the way down to small activities

- Constructive alignment gives us a systematic way to ensure everything is designed in service to learning.

- Curriculum mapping gives us a way to think more broadly in terms of the relationship between classes and other units of learning.

- Making our own judgements and being critical and reflective about how we approach our work, can help us to be better designers.

Revisit Guiding Questions

Now that you’ve revisited some established instructional design models and ways of thinking about lesson planning / learning design, if someone were to ask you what an ‘advanced’ method of instructional design entails, what would you say?

Conclusion / Next Steps

How that we know a little about more advanced topics in Learning Design to help us think more broadly and more critically, in the next chapter we’re doing to dig deep into this process and explore the steps we go through and the things we need to think about when designing a learning experience.

References

Anderson, L., & Krathwohl, D. A. (2001). Taxonomy for learning, teaching and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. New York: Longman.

Bates, T. (2020). What is the difference between competencies, skills and learning outcomes – and does it matter? Retrieved from https://www.tonybates.ca/2020/10/22/what-is-the-difference-between-competencies-skills-and-learning-outcomes-and-does-it-matter/ Aug 12, 2021

Biggs, J. (1996). Enhancing teaching through constructive alignment. Higher education, 32(3), 347-364.

Biggs, J. B., & Collis, K. F. (2014). Evaluating the quality of learning: The SOLO taxonomy (Structure of the Observed Learning Outcome). Academic Press.

Biggs, J., & Collis, K. (1989). Towards a model of school-based curriculum development and assessment using the SOLO taxonomy. Australian journal of education, 33(2), 151-163.

Bloom, B. S.; Engelhart, M. D.; Furst, E. J.; Hill, W. H.; Krathwohl, D. R. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals. Handbook I: Cognitive domain. New York: David McKay Company.

Clark, R., Bell, S., Roccisana, J. et al. Creation of a novel simple heat mapping method for curriculum mapping, using pathology teaching as the exemplar. BMC Med Educ 21, 371 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-021-02808-3

Dyjur, P. & Kenny, N. (2015, May). Analyzing curriculum mapping data: Enhancing student learning through curriculum redesign. Paper presented at the 2015 University of Calgary Conference on Postsecondary Learning and Teaching, Calgary, AB.

https://taylorinstitute.ucalgary.ca/sites/default/files/resources/handout_CR_5_analyzing_CM_data_2018_01_22.pdf

Furst, E. J. (1981). Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives for the cognitive domain: Philosophical and educational issues. Review of Educational Research, 51(4), 441-453.

LaFever, M. (2017). Using the Medicine Wheel for Curriculum Design in Intercultural Communication: Rethinking Learning Outcomes. In Promoting Intercultural Communication Competencies in Higher Education (pp. 168-199). IGI Global.

Morris, S. M. (2018). Critical instructional design. An Urgency of Teachers.

Tyler, R.W. (1949). Basic principles of curriculum and instruction. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Further Reading

Constructive Alignment, Teaching and Learning at University of Tasmania. Retrieved from https://www.teaching-learning.utas.edu.au/unit-design/constructive-alignment on Aug 12, 2021

Indigenising Curriculum Mapping Report – University of Queensland. Retrieved from https://itali.uq.edu.au/files/13184/Indigenising-curriculum-mapping-report.pdf

Did this chapter help you learn?

100% of 1 voters found this helpful.

Provide Feedback on this Chapter