What is the process for designing an experience?

Overview

In this chapter we’ll be digging deep into the process of designing learning digital experiences and all the considerations we need to make when involved in that process – everything from pedagogical to technology considerations.

If you need a review of specific instructional strategies and approaches for different modalities, or how to integrate technology into your teaching, check out the book Introduction to Learning Technology, and the following chapters, specifically:

Why is this important?

Designing learning experiences is a complicated and multifaceted process, and when we add technology to this process, it complicates things further – not in a bad way, we just more puzzle pieces to keep track of. While the models and frameworks that are documented for instructional and learning design work are a great place to start, the level of detail they go into is left quite generic so that teachers and learning / instructional designers can take from them what they need to. It’s important then, to dig deeper into how we design learning experiences that involve technology and what key considerations in each step in these frameworks might be.

Guiding Questions

As you’re reading through these materials, please consider the following questions, and take notes to ensure you understand their answers as you go.

- When you’re planning a lesson, how do you think about it, and what approach do you take?

- How have the assignments you’ve completed as a student helped you to learn?

- What learning activities have you participated in that have helped you to succeed?

- What are the best learning materials you’ve read / watched / listened to?

Key Readings

Fawns, T. (2022). An Entangled Pedagogy: Looking Beyond the Pedagogy—Technology Dichotomy. Postdigital Science and Education, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-022-00302-7

Designing for Learning

Now that we know about all the different models and frameworks for instructional and learning design, we can start to think about the details of actually doing it and how technology plays a role in everything we do.

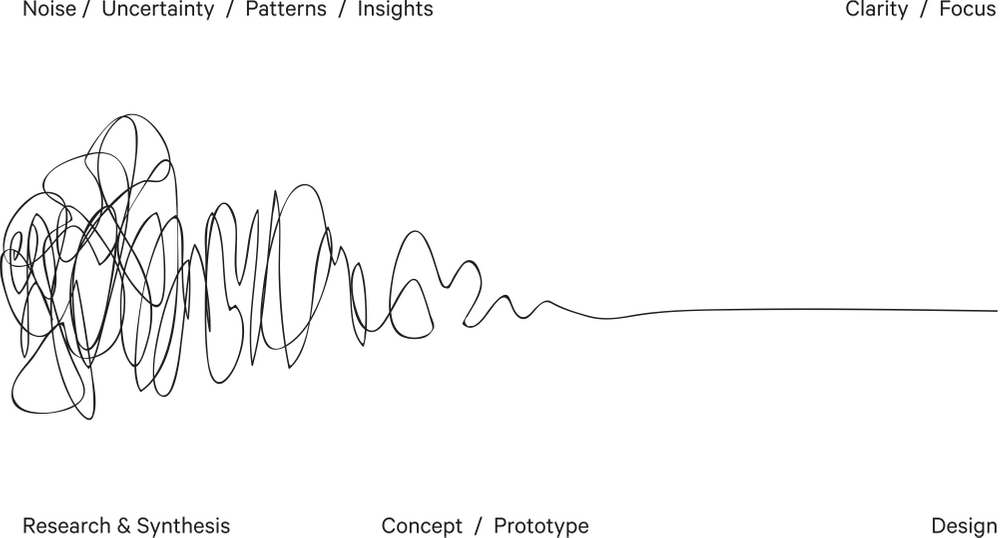

First of all, this process, despite what the frameworks give us, is usually a non-linear process and quite messy, with ideas jumping around in our heads and our actual work jumping back and forth into different elements here and there until complete.

The rest of this chapter is outlined in a ‘backwards’ design model, however as the ‘squiggle’ below outlines, many times this is not a clear process and we tend to jump back and forth and revise as needed.

If your process looks like this, you’re on the right track, so don’t feel discouraged if things don’t make sense, ducks aren’t in a row or everything isn’t in its right place. This takes time, and iteration and is part of designing anything.

The following material was originally written by the author for the Educational Technology Support (ETS) unit in the Faculty of Education at the University of British Columbia in mid 2019.

Writing Good Learning Objectives

Learning Outcomes (or learning objectives) form a very powerful conceptual foundation for how a degree, program, course, unit or lesson can be setup to ensure students learn what they need to learn. Outcomes are usually stated as clear, and measurable competencies for what a learner will be able to do once they have completed a learning experience at any level. Degrees, Programs, Courses, Units and even Lessons can have stated learning outcomes to assist in guiding how learners may achieve these goals.

*Note that some learning experiences including MOOCs do not need to measure student learning, and instead provide students with more reflective and transformative learning experiences may not apply to some of the principles outlined on this site.

Terms

First, let’s discuss some terminology. You’ve no doubt hear many terms revolving around the concept of learning outcomes, including the following:

- learning outcomes

- learning objectives

- learning goals

- competencies

- masteries

- skills

- instructional goals

The list goes on, however given that english is a language that allows for many interpretations of the same thing, many of these terms can be synonyms for each other, being used in different contexts for different purposes. Goals are sometimes interpreted as a more personal plan, as opposed to demonstrating what has been learning. Competency is, however, used in more polytechnic and training environments, describing a learners ability to complete a task or demonstrate a skill – this is more of a binary concept – either learners can do it or they can’t, whereas other concepts like outcomes are goals can be mastered at varying levels of proficiency.

As a result, it is usually easier to write a list of competencies students need to perform in specific contexts, however the rest of this section will focus on the more challenging process of writing learning objectives.

What are Learning Outcomes and how are they useful?

While learning aims usually refer to the instructor’s intentions internal to the class itself, class / subject / unit learning outcomes are usually clear and measurable descriptors of a learner achievement, usually as mastery of a skill applicable in the real world. Learning outcomes are used as a baseline to set expectations around what the student should be able to do when the learning experience is over, and ideally, if the this expeirence contributes to professional practice, what learners can do after they graduate.

Learning Outcomes, in a learning or instructional design process are able to be measured in such a way that assessment tasks / assignments can collect evidence of mastery at different levels, and thus are very useful in forming the backbone of any learning experience.

How can I write good outcomes?

Good learning outcomes should always be written from the perspective of the student, and be clear enough that students can have a good understanding of what they’ll be learning and what they’ll be able to do when the class is over, even if they currently lack domain knowledge. This helps to build motivation for the students from the outset, so they understand what they’ll be working towards. The preferred wording to use is this:

At the end of the class, you will be able to…

Traits of well-written learning outcomes

You may have heard of SMART goals before – that learning objectives should be:

- Specific – target a specific area for improvement.

- Measurable – quantify or at least suggest an indicator of progress.

- Assignable – specify who will do it.

- Realistic – state what results can realistically be achieved, given available resources.

- Time-related – specify when the result(s) can be achieved.

Some educators absolutely LOVE this concept of developing outcomes or objectives, while others want to take different approaches. An alternate way of frarming these goals is outlined with the following traits:

- Learning outcome is Measurable – can be assessed as complete/incomplete or on a scale (e.g., from 1-10; from developing to exceptional);

- Learning outcome is Transferable – speak to skills that can be transferred to other situations and contexts;

- Learning outcome is Applicable – speak to how the learner will use these skills beyond the classroom environment;

- Learning outcome is Realistic – speak to attainable skills, based on the class’s placement in the sequence of the program;

- Learning outcome is Clear – learners will be able to understand what they will be able to do, even if they currently have limited domain knowledge.

Whichever traits you choose to adopt or focus on, the important thing is that you’ve thought about what your students need to be able to know or do at the end of the lesson or unit of learning you’re working on. If the outcomes don’t fully represent this, it may have knock on effects as you develop your assessment strategy.

The Verb

And what is it the learner will be able to do? As noted in the last chapter, many instructors start with a verb, in some cases it may be something like ‘remember’ or ‘describe’, or ‘demonstrate understanding’. These words are usually sourced from Bloom’s (1956), and Anderson and Krathwohl’s (2001) revised taxonomy for learning in the cognitive domain. Common critiques of this taxonomy speak to its being published in a time when the learning sciences were just starting to explore issues around instructional design and learning itself, and that research in the field of education has advanced so much in the last 60 years, that other frameworks and models may contribute to the design of learning experiences in more meaningful ways. Regardless of the verbs that are used it is important to consider whether they are accurate for application in the real world, outside of the classroom.

For example, outcomes related to remembering certain concepts, could be expanded to consider the application of that knowledge in the workplace. As most of us do not go to work, and spend all day at our desks remembering or describing things – we apply that knowledge in very specific ways – it is important to consider that students will be wanting to apply what they learn outside of the class.

It is also useful to consider the verb in terms of its immediate context, if learners are to write something, what are they writing? If learners are to create something, what are they creating?

Samples: At the end of this class you will be able to:

- Write a report…

- Critically select Learning Materials…

- Provide feedback…

- Teach grade 3 students…

- Resolve a dispute…

- Use Adobe Photoshop…

The Application

After the verb and any associated artefacts or interventions, the next part to write is the application of that verb in context. If the verb is related to the a general scenario that exists in the future day to day work of the learner, then this can be used to flush out the outcome. More specific contexts can be used, depending on the class or unit and its role in scaffolding learners in their achievement of Program Learning Outcomes.

Samples:

At the end of this class you will be able to:

- Write a report detailing the sequence of events in assisting a mental health client in crisis.

- Critically select Learning Materials for specific grade and subject for distribution in an International Baccalaureate School.

- Provide feedback to other instructors on their facilitation of group work in different grade levels of subject area classrooms.T

- each grade 3 students the foundational aspects of a variety of science-related concepts.

- Resolve a dispute between coworkers in various stages of escalation.

- Use Adobe Photoshop to create a tourism poster for your hometown

But what about knowledge of new concepts and theories?

These may be more appropriate to be written as Learning Outcomes at a lower hierarchical level, like a module or week, which support the achievement of broader, Class-level Learning Outcomes.

Planning Assessment Tasks / Assignments

What is an Assessment Task?

For more on the definition of Assessment and some more on alternative assessments with technology, check out How do we Facilitate Learning with Technology?

Assessment Tasks (or Assignments) are instructional strategies used to collect evidence that a student has mastered specific class or unit outcomes. It allows us as instructors to measure whether learning has occurred or not, based on a set of benchmarks that we define. How our learners provide this evidence can vary from the creation of an artefact such as an essay, video, performance or presentation, to their performance on a quiz, exam or skills demonstration.

There are two types of Assessment Tasks.

Summative Assessments are tasks given to learners which provide the opportunity to demonstrate mastery of specific unit or class level learning outcomes, while at the same time, allowing instructors to measure whether learning has occurred. If the learner cannot demonstrate mastery of this outcome, learning may have not been achieved at the appropriate level. Generally Summative Assessments are for a grade.

Formative Assessments (or Activities) serve to allow students to process new information, integrate them into their existing knowledge base and work to understand relationships between theory and Practice. These are the activities in which learners practice at becoming proficient in different skills, while continuing to understand new information they have ben exposed to. Formative assessments can be for a grade, but sometimes ungraded.

Authentic Assessment

Whatever we expect our learners to do and create should ideally be tied to the skills and abilities they will apply after they have graduated, either in the work place or in home life. For this reason we should consider how the tasks we set for students can demonstrate how they will apply what they learned in each unit or class in the real world, and develop assessment tasks that reflect these skills. This means that we will engage in Authentic Assessment, which refers to the practice of providing learners with Assessment Tasks that closely resemble practices in the workplace.

Is there a difference between KNOWING HOW TO DO and DOING?

When planning and developing Authentic Assessment Tasks, we must consider the difference between knowing how to do something and doing it.

SCENARIO: Let’s imagine a preservice teacher needs to be able to make appropriate choices in the integration and application of technology in the classroom.

Knowing How: One way to assess this would be to have the learner research some technologies, and write a report on what technology they chose and why. This assessment task definitely measures their ability to know how to do what we’ve asked, but doesn’t provide any evidence that they can actually do it. It is therefore not an authentic assessment because it is a task that learner completes within the context of the class, but may not be beneficial to them after they graduate, as they will most likely never need to write a report like this again.

Doing: An authentic assessment based on this same example would be to give the learner time to research a technology and plan a mini-lesson using it. They would then deliver this to their peers, then answer questions after the lesson to speak to why the choice was made. This assessment task is more authentic because the learner is demonstrating they can do what we want them to do, not just know how. As an added benefit, now that they have completed this task, they can go into their classrooms and apply what they have learned.

How to develop Assessment Tasks

Developing Assessment Tasks requires a lot of imagination, so while it may be comfortable to refer to examples from your own experiences as a student in terms of how you were assessed, these may not be the most engaging, fun, or valuable experiences for your own learners (i.e. teaching the way you were taught).

The first step in developing and Assessment Task is to look at a Unit / Class Learning Outcome you wish to measure. When considering this outcome, what would it look like in the workplace for you to see a seasoned expert demonstrating their time-tested mastery of this outcome? After picturing that, try to imagine a scenario either in class or somewhere on campus where you see a learner doing the exact same thing. Are other people involved? Is the learner using specific equipment? Is the learner talking through what they’re doing, or just silent?

The goal here is to develop a task the learner can complete in such a way that they demonstrate they can do what your outcome describes. You may need to involve other students, have them verbally debrief their experience or even teach others as part of the task. Whatever task learners are asked to complete, it should be valuable to them after they graduate, either in the form of an artefact they can use in the workplace, or a skill they can impart to others.

Another point to consider is how and what an assessment actually measures. Our first time running a new assessment may garner results that are not so ideal, for example students may misinterpret instructions, or may follow the instructions perfectly, but may not demonstrate what they’ve learned. To avoid this, it’s good to think critically about the assessment tasks we design as well as their instructions to ensure that they are actually measuring what they’re intending to measure. This goes back to the alignment between objectives and assessments – if they don’t align, we might need to adjust one or the other to do so.

One scenario that may come up in our non-linear and ever-winding journey of developing a learning experience is that there simply be no way to effectively measure a student’s ability to do something in the real world. If they are learning how to perform complicate surgery on an endangered species or if they need to handle sensitive nuclear materials, these simply may not be possible to assess authentically. In this case, we must think of a way they can be assessed that most closely aligns with a real-world scenario, and most importantly, we must adjust our learning objectives to match what they do. (e.g., Student will be able to perform heart surgery on a northern white rhinoceros —> Students will be able to complete a simulation of heart surgery on a northern white rhino in a VR environment with 90% effectiveness).

BUT…My learners need to KNOW things! I should be assessing their knowledge!

This is very true. It is common to assess learner understanding of certain topics, but as described above, Summative Assessments are generally in place to provide learners the opportunity to demonstrate mastery of an outcome. If they are still processing newly acquired information and forming relationships between theory and practice, they are not ready to provide evidence of mastery. It is more appropriate then, to use Formative Activities to assist learners in their acquisition of knowledge and skills. In areas like health sciences, medicine, law, policy and other subject areas, entire years of study can be devoted to the acquisition of knowledge, so considering how this knowledge can be applied, the earlier this can happen, the better.

It is also important to consider that if our class / unit outcomes are supportive of each other, then learners simply would not be able to demonstrate mastery of a skill or ability without having already consolidated their understanding of new concepts, terms and practices. In fact understanding of new information is a prerequisite for mastering a skill.

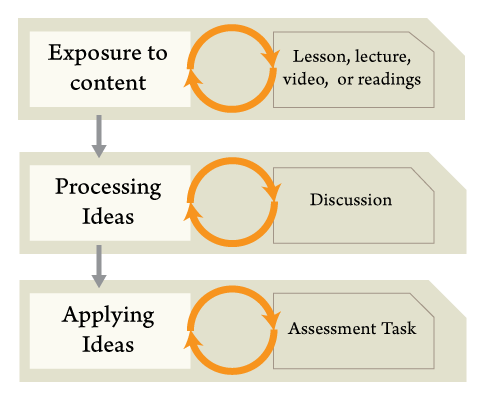

Formative Activities

Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development describes something more commonly known as ‘scaffolding’ – in some situations, learners have the ability to complete certain tasks on their own given their own level of expertise, but when engaging with new information, concepts and skills, learners cannot be expected to complete certain tasks on their own – they need support from an expert, usually an instructor. As learners work through the acquisition of new knowledge, concepts and practices, by forming connection with what they already know and practicing the application of this new information, they will be supported by experts (instructors), and form their own knowledge in a peer group with each other (see social constructivism). The activities and materials they are tasked with reading, watching and completing should facilitate this process, and contribute to moving them in stages through levels of expertise.

Activities that support learners in their mastery of class or unit outcomes are usually just referred to as ‘learning activities’, though it may be more useful to think of them as formative activities because they usually serve to move students through the formative stages of learning, until they are able to demonstrate mastery through successful completion of a Summative Assessment Task.

Think about this way: Formative Activities are just opportunities for learners to fail in a safe environment, with minimal consequence, until they are ready to provide evidence they’ve learned something.

Some instructors may choose to provide Formative Assessment Tasks, with a grade attached, which are intended to measure the learners progress in attaining specific skills. As learners do progress at different paces, and make connections in different ways, awarding marks for a formative assessment may put certain students at a disadvantage. It is recommended then, that formative activities are used by the instructor to informally gauge learner progress, instead of formally quantifying it with a grade.

These activities can take on any form, so can be quite varied in their intent and application. By considering the skills learners must develop to meet class outcomes, these formative activities should provide the learners the opportunity to make connections in knowledge, and practice skills enough to build to mastery. In other words, they should prepare the learner to successfully complete the associated assessment task.

Learning Materials (A.K.A. The content)

The materials provided to students should give them new information related to theory, practice, application of knowledge and critical reflection on the subject itself. Learning Materials used to be primarily in the form of textbooks, compiled and edited by experts in the field, but as information has been democratized through the advent of online technologies, many instructors are using open educational resources – resources they find online created by other instructors and experts, who create and share with the world.

Selection of learning materials should ideally be tied to formative activities, and supporting learners in the development of skills necessary to achieve class or unit learning outcomes. Any learning materials that don’t meet this aim, may not need to be included in the class.

There is also a robust area of inquiry around Learning Materials Design, and how learners engage with them. As such learning materials should be chosen based on their ability to promote learner agency, foster collaboration, and solidify concepts, while also being dynamic and engaging.

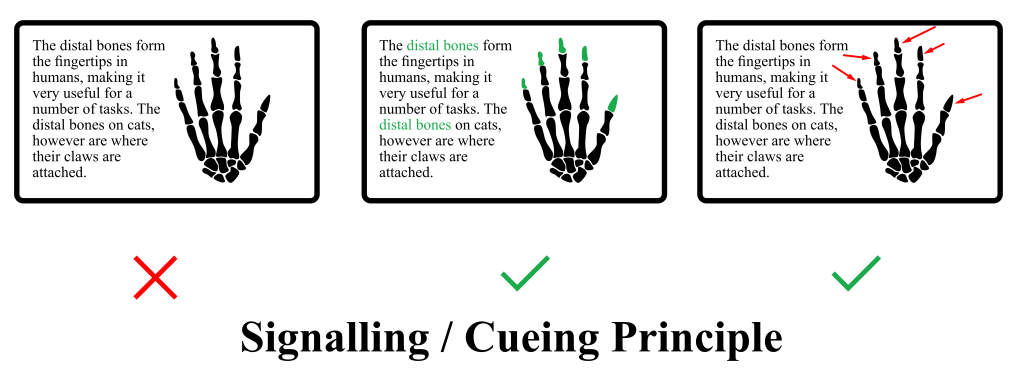

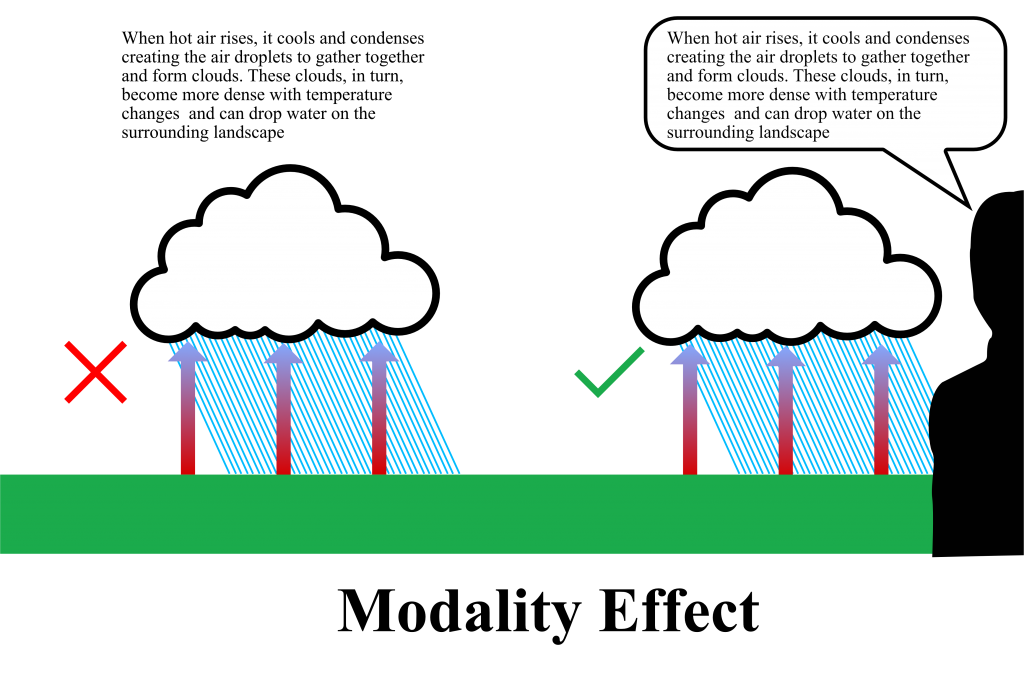

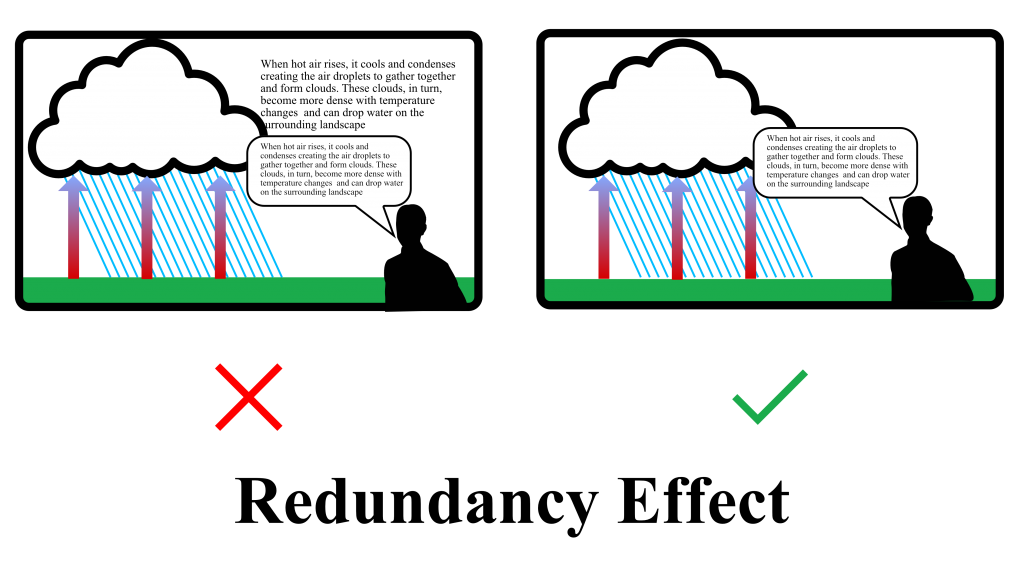

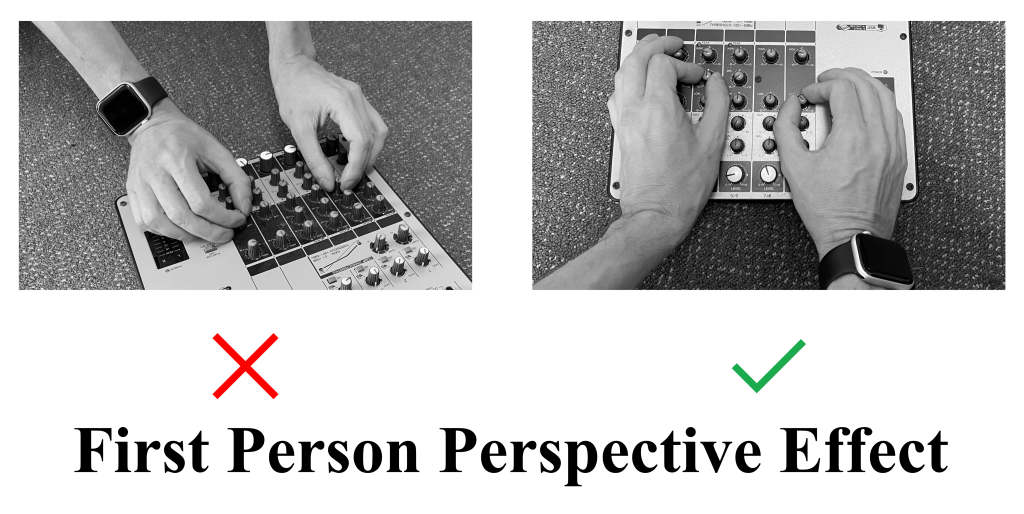

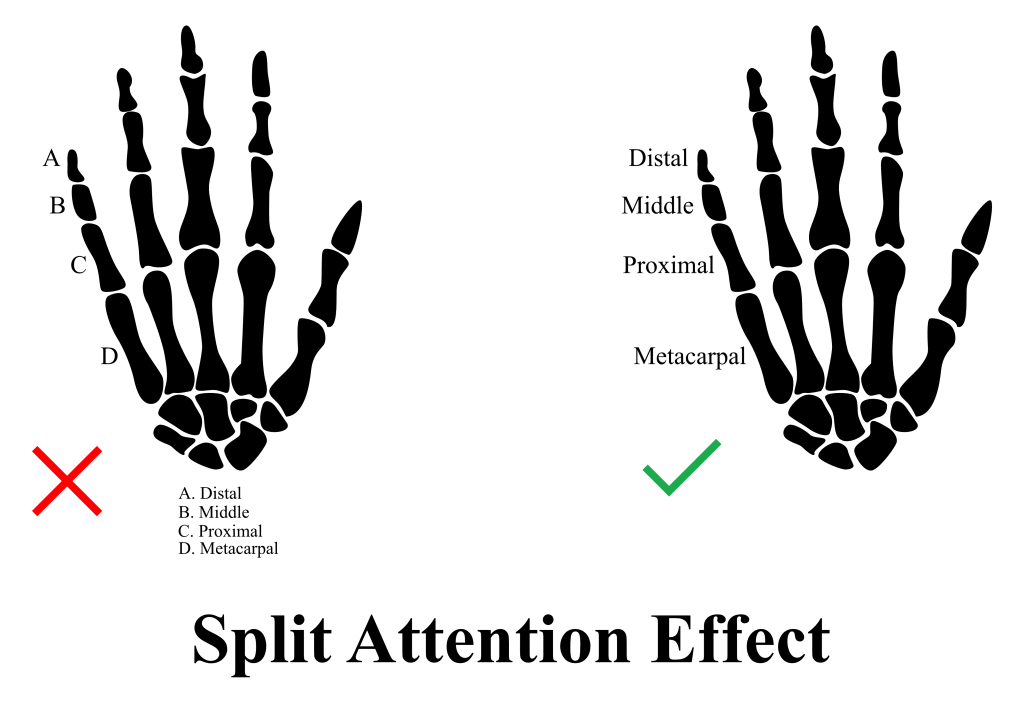

In addition to Mayer’s Theory of Multimedia Learning and Cognitive Load Theory, there is a lot to consider when designing and presenting content. Almost all of these effects and principles have to do with ensuring a learner’s attention is focused where it needs to be, capitalising on human relationships and body movements, and making sure students don’t get ‘overloaded’. The following table and slideshow outline just a few of these principles and how they can be applied for online / digital learning from Sepp, et al. (2021).

Note that this article is not available, but Castro-Alonso et al (2021) covers similar ideas.

| Effect / Principle | Instructional Implication / Tip for Practice |

|---|---|

| Split Attention | When presenting visual information such as diagrams or graphs with explanatory text, place text within the diagram, at spatially nearby locations, instead of off to the side or below, like a map legend. |

| Modality | When using multimedia, ensure that auditory (verbal) explanations support visual materials (text or images) without being redundant. |

| Redundancy | Like modality, when presenting novel information to learners, ensure that auditory and written explanations do not replicate already-presented visual information exactly, but instead highlight key points and serve to enhance learner understanding. If redundant information is present, consider removing it. |

| Signalling (Cueing) | When presenting novel information, add visual cues to guide learner attention to key areas either by using colour, symbols or text on diagrams. |

| Transient Information | When using multimedia materials, ensure that new concepts are not covered too quickly, and instead slow down the presentation, ‘chunk’ information into smaller, more digestible resources, or allow students agency to control playback of these materials. |

| Instructor Visible | When teaching online instructor presence is crucial to establishing community through social connections. Additionally, when presenting information through video or multimedia, a visible instructor who gestures, or provides other visible cues to guide attention can support learning. |

| Human Movement | Like the first-person perspective effect, when presenting procedural motor tasks for students to learn, use animations, and present them from a first-person perspective. |

| First-Person Perspective | In learning domains that involve procedural motor tasks such as learning a new skill using one’s hands, presenting video demonstrations from the first person, instead of the third person perspective, can support learning. |

Technology

When considering the non-linear nature of this work, one aspect we always jump back and forth to is the technology that will support our pedagogical goals or intentions. This means that the things we want our learners to do, and the technologies that we choose to engage them with will most likely be not set in stone from the beginning, and will change based on numerous factors just by the nature of the progress we make as we go.

Selecting learning technologies is already covered in the What Makes Technology Good for Learning? chapter, so feel free to revisit this to make your technology choices. It should be noted that some educators may gravitate towards the ‘Pedagogy before Technology’ paradigm that says we should always develop our pedagogical approaches THEN select a technology to support it, while others take a more nuanced approach. Fawn (2022) describes an ‘Entangled’ pedagogy, one that assumes technology will be integrated and that we must consider the relationship between technology and pedagogy as we develop learning experiences, while also engaging with our colleagues, students and other parties to do so. With this approach, the realistic process of learning design is accounted for, with the process being at times uncertain, imperfect and non-linear in nature.

Differentiation and Universal Design

There are many facets to a learning experience that we might want to build in, but an important one is differentiation, a teaching strategy that allows us to respond to individual differences in our learners. Differentiation and a related concept, Universal Design for Learning (UDL), have historically been considered related, and in Griful-Freixenet, et. al’s review (2020) found that many educational researchers see this relationship through different lenses. In some circles, UDL is seen as something that is done proactively to ensure all students can access materials and express their learning through multiple modalities and gives them a choice on how access and create. Differentiation, on the other hand is a reactive teaching practice that uses formative assessment to inform teaching practice to adjust a learning experience that meets them where they are in terms of their readiness for the topic, what they’re interested in, and their learning profile. According Griful-Freixenet et al’s review, there are 3 different ‘camps’ as to how UDL and DI are related:

- They are separate but interrelated strategies, with UDL framed as a pedagogical model to promote equal access, and DI a teaching strategy aimed at meeting students where they are in terms of what they’re learning

- UDL is simply a part of DI

- UDL and DI are completely separate and unique.

For more details on this topic, see the NSW Dept of Education website and the VIC Dept of Education website, which both interestingly don’t mention access at all. What do you think? Are UDL and DI related? Do they have similar or different aims?

One common analogy that can help to frame this question is to imagine boats in a harbour: While UDL aims to raise all boats in a harbour to ensure they are at an equal level, with the same chance of getting out for a sail, DI allows boaters to use boats of varying levels of complexity, from row boats, to motorboats, and jetboats with complicated controls. They’re all boats, but some take more skill to operate.

Learning Interface Design

A field that is rarely discussed overlaps Interaction Design, User Interface (UI) Design and Learning / Instructional Design to focus on the design of interfaces in learning systems. While this can take a more technical approach (such as developing websites specifically for learning), the related design approaches are good to know, just to be able to organise things within the systems we already use. This side of the ‘usability of digital learning experiences’ is something that is rarely discussed in the literature concerning instructional or learning design, and while we don’t have control over our platforms like Google Classroom or Canvas or Moodle, we do have control over where we put stuff.

The following video is part of a lecture series for an interaction design class, so as it is geared to more of a design field, feel free to jump around to find info thats useful for you.

So part of designing learning experiences that involve technology, especially those in blended or fully online modalities, is to think about the layout and navigation, and even the instructions we give our students and the format and layout of those instructions. Even the aesthetics of the design including how much white space there is, what font is used and if the platform is responsive and works well on mobile devices are important factors to think about.

When considering how to design online learning experiences and the interfaces that go with them, sometimes we encounter changes and design choices made by the platform developers that may may things confusing. This video shows a minor design change within the Canvas LMS that was pushed to users in 2019, and the design features that may cause confusion.

Additionally, how content is presented within a learning platform can also be a factor that can influence learning, as noted in the excerpted below (originally from this 2017 blog post)

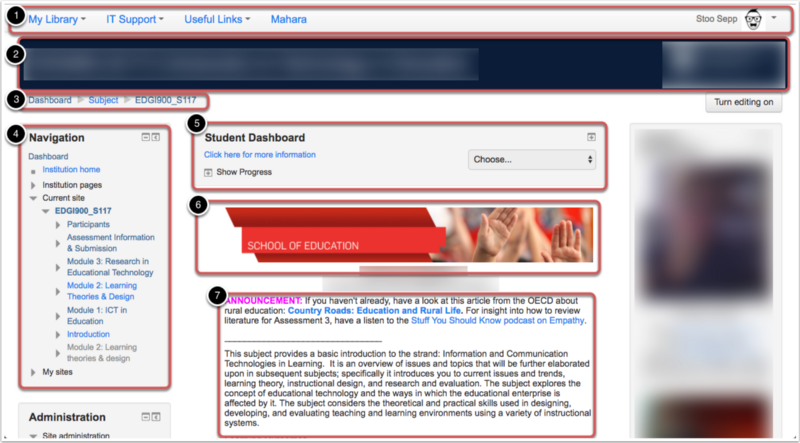

Above you can see a class setup with a typical theme in Moodle. Of course other Virtual Learning Environments (VLEs, otherwise known as LMSs) will have a different theme and setup, but for the purposes of this examination, it would be good to use a free, and open source product that is in use in many institutions worldwide. So let’s have a look…

- Top Navigation Bar

- Class Name

- Breadcrumb Navigation — for navigating within the class

- Blocks (present on both sides as well)-these present lots of different kinds of information, from links, images, polls and other content, but are typically static across all content / assignment pages

- Dashboard link — in this instance, I have no idea why it’s there.

- Banner — banners are very common in order to show a visual similarity for classes within the same program. If you have many programs at one school, then banners have typically been a way to differentiate, so students can easily tell what department’s class they’re in.

- Class content.

Looking at the elements presented above for a 1280 x 720 screengrab, only 600 x 299 pixels of that is devoted class content, or approximately 15% of the entire screen.

This is what we want to avoid, because students come to an online space to learn, and showing them a whole bunch of information that is not really relevant to their learning is less than ideal.

Key Take-Aways

- There is much more to learning design than simply following linear frameworks and models of the process.

- Considering what and how your learners need to learn something is at the core of designing a good experience

Revisit Guiding Questions

Now that you’ve read about more in-depth approaches you can take to designing learning experiences, answer the question the title chapter poses: “My process for designing learning experiences involves …”

References

Anderson, Lorin W.; Krathwohl, David R., eds. (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives. Allyn and Bacon. ISBN 978-0-8013-1903-7.

Bates, T. (2020). What is the difference between competencies, skills and learning outcomes – and does it matter? Retrieved from https://www.tonybates.ca/2020/10/22/what-is-the-difference-between-competencies-skills-and-learning-outcomes-and-does-it-matter/ Aug 12, 2021

Bloom, B. S.; Engelhart, M. D.; Furst, E. J.; Hill, W. H.; Krathwohl, D. R. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals. Handbook I: Cognitive domain. New York: David McKay Company.

Castro-Alonso, J. C., de Koning, B. B., Fiorella, L., & Paas, F. (2021). Five Strategies for Optimizing Instructional Materials: Instructor-and Learner-Managed Cognitive Load. Educational Psychology Review, 1-29.

Fawns, T. (2022). An Entangled Pedagogy: Looking Beyond the Pedagogy—Technology Dichotomy. Postdigital Science and Education, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-022-00302-7

Griful-Freixenet, J., Struyven, K., Vantieghem, W., & Gheyssens, E. (2020). Exploring the interrelationship between Universal Design for Learning (UDL) and Differentiated Instruction (DI): A systematic review. Educational Research Review, 29, 100306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2019.100306

Rey, G. D. (2012). A review of research and a meta-analysis of the seductive detail effect. Educational Research Review, 7(3), 216-237.

Sepp, S., Wong, M., Hoogerheide, V., Castro-Alonso, J.C.(2021) Shifting Online: 12 Tips for Online Teaching Derived from Contemporary Educational Psychology Research. Manuscript submitted for publication.

Further Reading

Did this chapter help you learn?

No one has voted on this resource yet.

Provide Feedback on this Chapter