How do we Learn with Technology?

Overview

Outcomes

- Understand what learning itself is

- Identify different contexts of learning

- Identify appropriate modalities for learning

- Consider individual differences in learners

- Differentiate between major learning theories

- Understand the basics of how people learn using technology

- Understand how to identify needs of learners to develop experiences that create equity amongst a group

Why is this important?

Key Readings

What is learning?

You have added much several ways, & especially in taking the colours of thin plates in philosophical consideration. If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of Giants.

-Isaac Newton, 1675

What is true however, is that learning usually cannot happen in a void. Anything new that we learn we are building on previous things we learn, whether we learn it in isolation by ourselves (e.g., YouTube Tutorial) or from other people (e.g., Attending a lecture or chatting in the pub). This is the foundational way to think about learning – that it’s a process of building upon something that’s already there, either in ourselves or in other people.

Learning is also something that is not done FOR you, but is something that YOU DO actively. Being given learning materials like a video or a book chapter to read and you reading them is not learning – it’s what you do with this experience, and how you link it and connect it to what you already know and how it applies to the real world – that’s when learning happens.

Some also argue that the result of learning is transfer of knowledge from one context to another. Transfer of knowledge refers to when we learn a skill in one subject area, and apply it to another (e.g. learning geometry then applying it to woodworking). In the research there are different kinds of transfer, including near transfer (applying the same problem-solving strategy to a very similar problem) or far transfer (apply a problem solving strategy learned in one subject area or domain and applying it to something completely different.

One thing is true is that when we learn, it’s not all smooth sailing – it can be frustrating, reducing our confidence and even making us question our ability to learn at all. Bjork and Bjork’s (2011) Desirable Difficulties speaks to this aspect of learning, in that while we may slow down with our learning and get confused or take more time to work things out and make connections, this often leads to more long term retention of knowledge, thus providing advantages in the long run.

In short, if you ever get frustrated when learning, this just means you’re learning 😉

Learning Theory from an Aboriginal Perspective

Before we get into the theories informed by western notions of education and research, it’s important to acknowledge the approaches taken by indigenous peoples in Australia and abroad, given that these approaches to learning are far older and more established than what contemporary views on learning articulate. While modern learning theory is only about 150 years old indigenous knowledges and pedagogies date back tens of thousands of years.

Allan Luke: Different Ways of Knowing the World from Professional Learning Supports on Vimeo.

Fundamentally aboriginal education and learning is based upon the relationships that people have to each other, the animals, and the land around them (Country), and everything stems from this. Stories are the primary means of conveying knowledge, and may come in many forms. If you’ve ever listened to stories told by elders (or aunties or uncles) in your community, sometimes their stories come in different forms than western stories – they may not have a middle or an end, they may rely on knowledge of a story you haven’t heard yet, or they may be circular. Additionally, some stories and knowledges have protocols around them, meaning they are only used for particular purposes. Teaching stories, for example are normally free to be shared publicly, where as other stories may be just for individual’s ears, or for specific members of a kin-group or family, based on gender, age or other factors, so if we wish to use any stories or knowledge, it’s important to ask community members about the protocols regarding what we want to share. It should also be noted that aboriginal approaches to learning are intergenerational, meaning that the knowledge shared and how it is shared spans many generations – this concept, while true in western ways of learning, takes on a different meaning and is built into the notion of respect, outlined below.

Yunkaporta developed the 8 Ways framework as a part of his thesis in 2009 as a means to share protocols around engaging cross culturally, not just between aboriginal and non-aboriginal peoples, but to inform any sort of relationship.

- Story Sharing – We connect through the stories we share. We can approach learning through a narrative, so personal narratives and stories are important.

- Learning Maps – We picture our pathways of knowledge. This means that explicitly using diagrams or visualisations of learning processes are important

- Non-verbal – we see, think, act ,make and share without words, meaning we can apply intra-personal and kinaesthetic skills to thinking and learning.

- Symbols and images – we keep and share knowledge with art and objects, so images and metaphors can be used to understand concepts and content.

- Land links – We work with lessons from land and nature, involving place-based learning, linking content to local land and place.

- Non-linear – We put different ideas together and create new knowledge, producing innovations and understanding by linking laterally (perhaps not always linearly).

- Deconstruct / Reconstruct – We work from wholes to parts, watching and then doing.

- Community Links – We bring new knowledge home to help our mob, making sure to center local viewpoints and applying what we learn to benefit our communities.

Canadian scholar Kirkness and Barnhardt (1991) also articulated the 4 R’s which are outlined below:

- Respect refers to respect for almost everything, respect for the people involved in learning, for the relationship between teacher and learner, to our elders and community leaders, who our learners are as people (including their strengths and weaknesses), between the land, the animals, and ourselves, between indigenous and non-indigenous cultures. It also refers to the respect for cultural histories and extends to the use of language. Given that education was essentially used as a means to harm indigenous populations in the past, respect can be the first step in the acknowledgement that while we may view the world in different ways, indigenous worldviews and viewpoints are worthy of both attention and respect.

- Relevance in the classroom or online should be embedded in learning experiences. From an indigenous perspective this usually refers to the links to cultural competencies and histories of people and places, and of stories and lessons previously learned. As you’ll read in the rest of this chapter, this principle resonates with may contemporary, and western-informed theories of learning as well.

- Reciprocity can take many forms, but it can be thought of in terms of relationships and how there is always a give and take in life and in learning. While older western notions of learning come with a ‘learners brains are empty and must be filled’, this idea of reciprocity speaks to the relationships we have between teacher and learner and that we all learn from each other, and learn to negotiate, even through disagreements.

- Responsibility plays a really important role in the learning process – either the responsibility of the teacher to instill knowledge, to fulfil their role as mentor and educator, as well as the responsibility on the part of the learner to listen to stories and lessons that will help them understand what they’re learning. For this author, its their responsibility to learn as much as possible about aboriginal cultures and ways of learning, and to share this in a respectful way that is relevant to their own learners.

We’ll address some more of these concepts in the chapter on facilitating learning, but for now, just be mindful that though these approaches may be fundamentally different from how you learned, or how you’ve been taught to teach or learn, they are definitely valuable additions to our ‘toolbox’ as educators.

If you don’t have as much exposure to aboriginal or indigenous culture as you’d like, you’re encouraged to explore this on your own, as this different worldview and approach to learning is a way to enhance your own reconceptualisation of what education can be. It should also be noted that many EDIT units in the Grad Cert Digital learning draw upon indigenous pedagogies and ways of knowing and learning. See if you can identify them 🙂

Learning Theories

You have no-doubt heard of the concept of Learning Theories before. These are frameworks developed by researchers over many years that help us think about learning in different ways. Some may view different learning theories as in opposition to each other – that one learning theory cannot be true, while another can. Learning theories, however can also represent how Learning Science (the field of studying how people learn and effective ways of learning) has changed over time. Learning Theories that were identified further in the past, simply represent how learning was understood at the time, with the next theory building upon the previous and so on. There will be more learning theories in the future, you can be sure of that.

Behaviourism

The foundational idea behind behaviourism is that learning is simply a change in behaviour, that if educators can elicit a change in behaviour that a student will have learned something. While this may be true in some contexts (e.g., reacting if you touch a cooktop as a child), other situations it doesn’t make sense at all. Behaviourism is sometimes also referred to as ‘conditioning’.

Major Theorists in this area are Pavlov (remember his dog?) – his type of behaviourism can be called ‘Classical Conditioning’. Skinner’s work in this area (see his video below) is called ‘operant conditioning’, and his research is where we get the terms ‘Positive reinforcement’ and ‘negative reinforcement’.

Cognitivism

Cognitivism came next – this is all about what learning is in terms of cognitive processes, memory limitations, processing of information and the construction of knew knowledge as memory traces in our brains. Essentially researchers exploring learning eventually thought that changes in behaviour and automatic responses to stimuli (e.g., dog salivating after hearing a bell) did not encompass the breadth of what learning actually was. Cognitivisim therefore assumes that learning is a process that takes place as a result of processes in the brain, not just because of external stimuli.

A researcher named Jean Piaget, who worked primarily worked to understand how children developed cognitively, coined the term ‘schema’ as a way to describe the interrelated structure of how we store information in our brain.

It’s important to know that while most of the resources you may find about schemes and schema may be about children, the concept of an interrelated network of information definitely still applies to adult learning, given that everything we know and learn essentially needs to be anchored to previous information.

A good way to think about schemas is just a network of connected nodes, like a mind-map or even a spider web, with each piece of information being a memory of what something is in your brain – like a database. Each database for everyone is different though, so when you see the word CAT, this word will immediately and automatically activate memories for you that will be different from every single other person on the planet, simply because we’ve all had different experiences and we have different memories.

If you’ve heard the phrase “activate prior learning” before in educational contexts, this refers to asking students to think about what they already know on a topic before they start to learn something new about it. This is rooted in the concept of schema, that asking students to think about what they already know, will allow them to incorporate, assimilate and adapt new information into existing structures in their brains.

While schema may be a theoretical construct, it is also very much a physical occurrence in the brain. Check out the video below of neural stem cells suspended in a medium. You can see the physical connections that these neurons are attempting to make with each other, demonstrating that learning is fundamentally (and biologically / neurologically) about the connections we make to existing structures. Cool huh?

Constructivism

Let’s go back to Jean Piaget. Through his work in exploring how children developed from a psychological perspective, he understood that all development and learning had to be based on a continual construction of knowledge and understanding, but how does this happen? How does new information get added to existing information?

- Assimilation is the means by which new information is added to our existing ‘database’ in our brain, by linking new information to existing information.

- Accomodation is the means by which our own knowledge and understandings are reframed to fit with new information or experiences that change what we already knew. This concept of accomodation is tied to the idea that we all learn by failing. Once we experience something that tells us we got it wrong, we are able to reframe our understandings so that we don’t fail again…or at least we try again … and again until we get something right.

Constructivism is a very important learning theory to understand because it assumes that when an individual learns, they are basing their understanding on their previous knowledge, and by extension their experiences. This means that no one person learns in exactly the same way as another, and that we all interpret new information based upon our existing understanding of things orbiting that new thing.

Social-Constructivism

Lev Vygotsky was a Russian Cognitive Psychologist who also understood that learning was not simply a response to stimuli and a change in behavior, however unlike Piaget, Vygotsky extended his thinking beyond the individual to social and cultural aspects of learning as well.

A special feature of human perception … is the perception of real objects … I do not see the world simply in color and shape but also as a world with sense and meaning. I do not merely see something round and black with two hands; I see a clock …

Lev Vygotsky (1933 – translation from 1968)

This quote is at the core of Vygotsky’s contributions to educational sciences in that he understood learning to be inextricably linked to how we are socialised, understand concepts based on shared social meaning as well as how we learn in social settings.

Check out Wikipedia for another good example of the clock concept above

Because, according to Vygotsky, we learn within the context of our society and culture, this means that learning does not usually happen in an individual vacuum – we learn together, socially. This is observable, and super interesting to note in monkeys and other non-human primates, who mimic the behaviour of older members of their social groups to learn new skills.

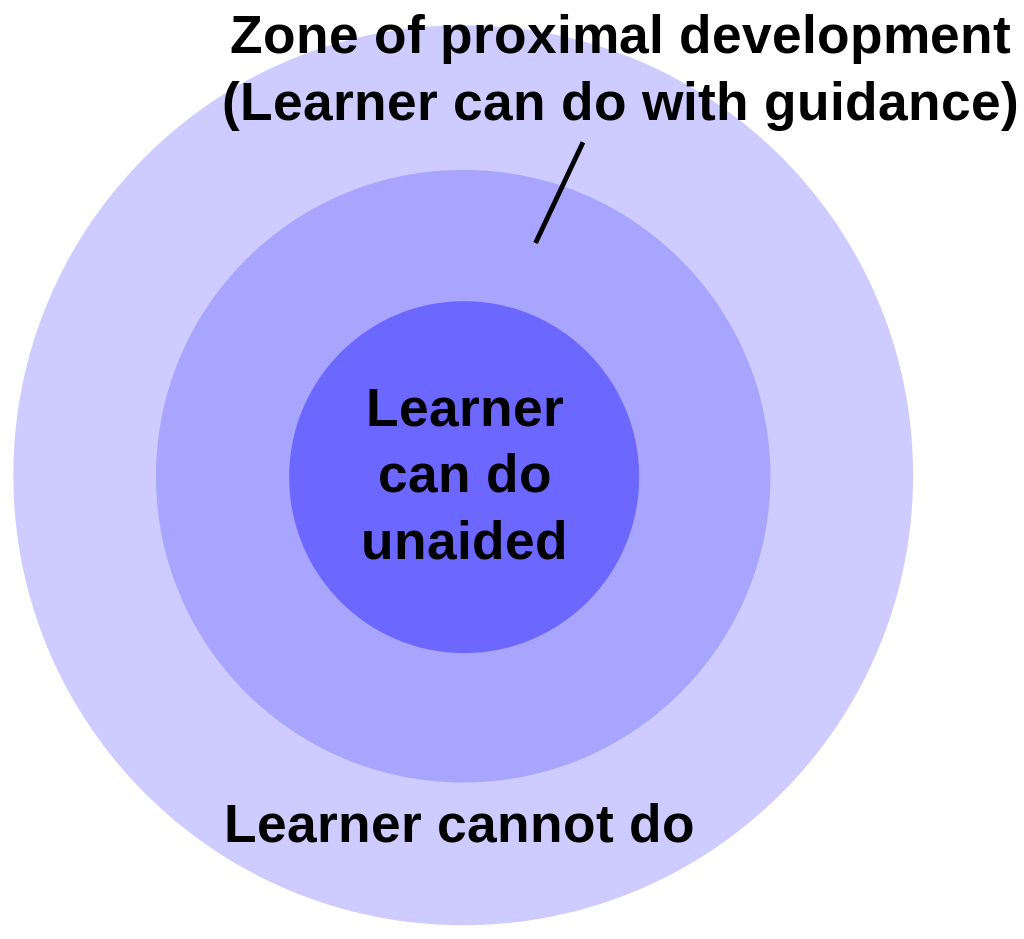

Vygotsky’s important contribution to education is built upon this concept – that we, as learners, are unable to perform skills or tasks without first having support from someone who has more expertise in this area. He called this the ‘Zone of Proximal Development’ – that is, the extent to which we are able to act on our own and be proficient is limited to a certain threshold, and beyond that threshold, we need help.

This is evident in almost all learning situations – such as at primary school, university, polytechnic and apprenticeship models. Learning in this way – a social way- allows us to almost be socialised into a specific way of doing things and working, which is specific to the culture in which we are embedded. For example, learning itself has a specific culture. You may have taken classes before where there is little or no interaction with the instructor (the expert) or your fellow students (other experts). How much did you learn in these situations?

With the rise of YouTube, including ‘how-to’ and ‘DIY’ videos, these resources tap directly into Vygotsky’s concept, by giving us access to experts in areas we could never have access to be before.

Hence, when we think about Constructivism, we don’t just make meaning for ourselves based on our own experiences, we do so in a social setting, learning from others and leveraging their experiences as well, hence Social Constructivism.

Constructionism

This term is sometimes misconstrued as a synonym of constructivism, but it’s not. Constructionism (Papert & Harel, 1991) is just an evolution of that concept that takes into account instructional practices like problem-based learning and role playing by purposefully having learners construct their own understanding and meaning of information, through specific experiences. It is built upon the premise of ‘learning by making’.

Whereas constructivism thinks of learning as how learners construct meaning based on novel information they are given built upon what they already know, construcTIONism pushes this a step further to say that the experiences a learner has while making something are what helps them construct brand new knowledge and understandings that have nothing to do with information they are given, but simply by virtue of the process of creation. This lends to a more exploratory model of learning, where new experiences lead to new understandings that may not even have anything to do with instruction.

Connectivism

This is one of the newest learning theories, dating back to around 2004 / 2005. Both Stephen Downes and George Siemens arrived at a similar theoretical conclusion that is rooted in the use of technologies that connect us. Essentially Connectivism says that as we interact through social, professional and educational networks, these networks allow us to both share information with each other and relate information to other information very easily, while at the same time. Another core tenet of this theory is that these networks and the relationship between connections in these networks is always changing, sometimes rapidly.

“Knowledge has many authors, knowledge has many facets, it looks different to each person, and it changes moment to moment. A piece of knowledge isn’t a description of something, it is a way of relating to something.”

– Stephen Downes

Connectivism is a good description of how learning occurs in a digitial age. No longer are we given chapters of books or journal articles to read, taking this information as gospel and then spitting what we read back out in the form of exams and essays. At this time, knowledge construction was quite slow – we would have to wait for a new version of a book to printed, which means it could take years to learn about something new. So-called ‘New’ media changed this, and with the advent of the internet, we are constantly engaging with multiple representations of the same information (e.g., videos, websites, professional networks). We are noticing how different people interpret the same information and most importantly we are able to build on existing ideas and share our own very quickly and easily. Connectivism also incorporates aspects of chaos and complexity in our learning experiences, that as we learn, the more what we thought we knew can be disrupted or reframed and this is not something we can control.

Do you want to know more?

There are far more learning theories and conceptions of learning that researchers and theorists have developed over the years. Below is a visualisation created by Richard Millwood in 2013.

Education or Training?

In some circles, people argue quite strongly that there is a difference between learning experiences in different learning contexts. For example, is Education and Training different? While there is no correct answer to this question, and it seems to be a philosophical difference in different educators its a useful thing to consider.

For training, we may argue that this is primarily about the performance of tasks, so more aligned with Behaviourism. People are trained how to DO something.

Education, on the other hand might be more about KNOWing.

This can also differ based on the setting where learning is happening. Is education different in schools vs. universities? What about polytechnic institutions (e.g., TAFE) or the military?

While it is an important thing to consider, another interpretation is that learning is learning, and where we learn and how we learn can differ based on the culture of where we are learning. This culture can change though, and it can differ, as some university programs may align more with behaviourism, while some military or workplace learning experiences may align more with cognitivism or social constructivism.

What do you think?

Learning Modalities

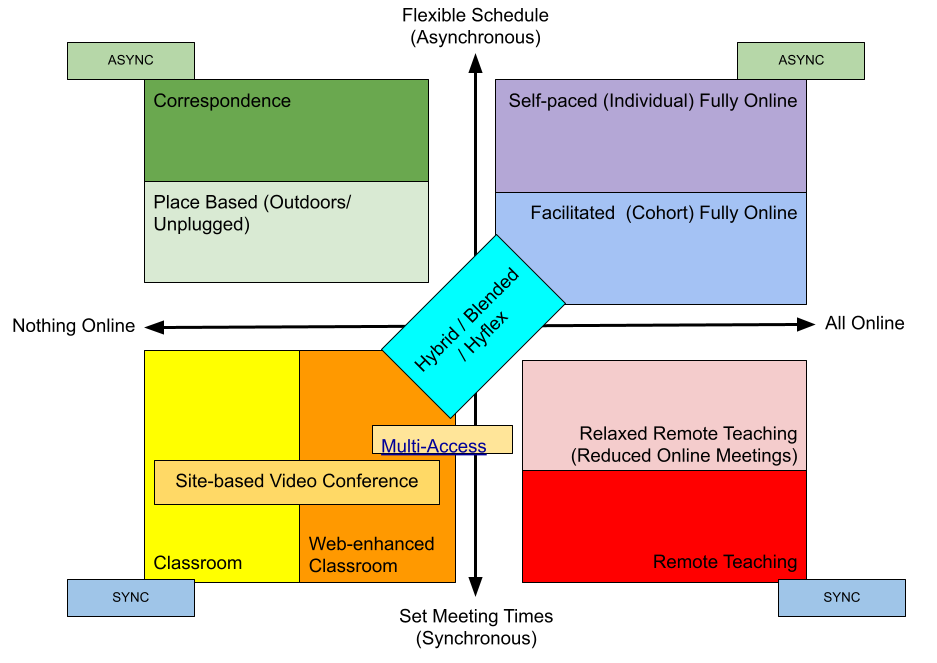

When we consider how people learn with technology, we first have to think about how they’re engaging with technology, and this can differ greatly – this leads to different ways of classifying learning with technology, and these classifications and terms can differ from country to country and organisation to organisation.

First, let’s talk about WHEN learners engage

Next, let’s consider WHERE students are physically when they learn.

Face-to-face (A.K.A. On-campus or F2F or in-person)

This is pretty straight forward. It’s learning in the traditional sense – in a classroom with a teacher (and maybe Teaching Assistants) and your fellow classmates. In recent years, a face to face classroom may leverage technologies, perhaps using an online platform to store PowerPoint Slides or allow for homework submission. Many organisations have different names for this, like ‘web-enhanced learning’ or a ‘digital classroom’. The key here is that in this type of classroom, no learning time is replaced with an online component – sure people might do homework online, but the actual design of the learning experience is intended to take place in the classroom.

Correspondence Learning

This was the first type of distance learning. In the early forms, it involved printing paper-based learning materials, along with assignment sheets and worksheets and mailing them to students, who were expected to complete and mail them back to their instructors within a given timeframe. In this modality, there was little to no interaction between learners. There was usually only one or two major assignments and the students could ask questions of their instructors, either by mail, phone or email.

Some online learning experiences may still feel like they are using this model, with the addition of more rich multimedia learning materials, housed online.

Independent Learning (or Self-Paced Learning)

The modern version of Correspondence Learning doesn’t have an agreed upon name, but it can be described as Independent Learning or sometimes Self-Paced Learning. This means that learners access an online system, and work on it at their own pace. Sometimes these systems allow for assessment and even interactions with other learners (which involves a limited form of social constructivism). Examples of these may include video tutorials (through sites like Youtube, Skillshare, Udemy or LinkedIn Learning) and may even encompass MOOCs (Massive Open Online Courses).

These types of learning experiences are most common in the private sector, in the form of professional development / learning experiences that employees must work through on their own to gain proficiency in a product or understand a specific process.

Distance Learning

This is just a catch-all phrase used to describe any sort of learning that happens at a distance. This includes classes that may be offered over videoconference systems, where learners at different sites show up to campus and engage in lectures or lessons with learners at other sites using specialised hardware. With the advent of more reliable Web-conferencings systems (e.g., Zoom, Teams, etc.) these types of classes are becoming more rare.

Online Learning (or ‘Fully’ Online Learning)

This modality is where 100% of all learning experiences happen online. Learning Materials, Learning Activities, assessment and interaction all happen online, and can take place synchronously or asynchronously.

Another term that is used to describe online learning is ‘Flexible learning’, however in some contexts, this can also mean Blended / Hybrid Learning as well.

Blended / Hybrid Learning

This form of learning usually means that the learning experience is comprised of a mix of online and face-to-face experiences, with a set amount of online activities or experiences displacing face-to-face time. Some organisations may define this ridigly to say that 3 days out of a 5 day school week happen online, whereas other organisations may just stick to the loose idea that online displaces face-to-face, regardless of the amount.

- Hybrid just means the learning experience is a literal hybrid of face-to-face and online.

- Blended, just means the same – we’re blending the two.

Flipped Classroom

This modality is more common in schools, both primary and mainly secondary. It leverages the idea that anything that happens face-to-face should be actionable, authentic and applicable to more real-world scenarios. In this modality, students engage with learning materials and complete learning activities online – this mainly focus on the underlying theory of something (e.g., chemistry, mathematics, art, etc.) – then in the face-to-face session that follows, they are able to take their theoretical knowledge and apply it in the classroom by conducting experiments, completing problems or creating something.

Hyflex (Hybrid Flexible) Learning

Hybrid Flexible Learning (or Hyflex) is a way to describe learning experiences that combine face-to-face with synchronous online learning, meaning students can show up to class, and also ‘show up’ through video-chat tools and participate as if they were in the classroom. While there are obviously limitations to what online students and do when ‘attending’ a face-to-face classroom, it’s important to be aware that these types of learning experiences are designed such that everyone has an equitable experience – students online should not miss out on opportunities simply because they didn’t physically come to class.

While Hyflex has been around for years, this modality grew in prominence during the COVID-19 pandemic. Due to unpredictable changes in health orders in different educational contexts, many students may not have been able to physically come to class, yet this should not negatively impact their learning progress. Many organisations are planning on continuing to work in this modality after health restrictions are lifted, simply because it allows instructors to meet students where they are and allow learners to engage in ways that fit their lifestyle and commitments.

Educause – 7 Things you should know about…Hyflex Learning

Multi-Access Learning

Multi-Access Learning takes Hybrid, Online, and Hyflex and mashes them together, allowing students to be able to engage in ways that work for them, when they want to. Face-to-face classes are held, with some students opting to physically be present, while others join through video-chat. There are also asynchronous and synchronous online activities, with online meetings and small student groups working together on collaborative projects. The key with this modality is that it provides student choice as to how they want to engage, and therefore how they want to learn.

Post-COVID Modalities

During the COVID-19 pandemic, many educators were unwillingly thrown into situations where they had never even considered how to teach online. Some worked primarily by using the ‘chalk and talk’ method of teaching – standing at the front of the room and reiterating concepts that were in their students textbooks, while others had been using more active learning techniques in their classrooms for many years.

The confusion during early 2020 when many organisations had no choice but to ‘pivot’ online, was that few knew how to refer to what they were doing? Was it online? Was it hybrid?

Many educators, by no fault of their own, erroneously referred to what they were doing as ‘Hybrid’, since they were delivering live lectures over video-chat while also having online activities. A new term that arose early in the pandemic was ‘Emergency Remote Teaching’ which describes the ‘quick and dirty’ adaptation of face-to-face learning experiences to online, usually taking the form of live lectures with online assignments and that’s it. Further pandemic reinforced many negative stereotypes around the quality of online learning, leading some articles criticise online learning or to extoll the benefits of face-to-face learning and the need to return to that modality as quickly as possible.

In the below podcast episode, Dr. Valerie Irvine, speaks about how the landscape and the modalities of online learning have shifted as a result of the pandemic.

The Landscape of Merging Modalities – Dr. Valerie Irvine (University of Victoria, Canada)

The Problem with Online Learning? It doesn’t teach people to think (The Conversation) – Do you agree?

Supporting Research areas for technology-based learning

Now that you’ve read a LOT about learning theories, and their historical progression, it’s time to think about a few areas of research that can help ground the use of technology and its use can support learning. There is so much to learn in this area, and entire books have been written on this subject. First, it’s important to understand that the same principles we know about learning face-to-face generally apply in technology-enabled classrooms and online learning – human brains are human brains, wherever they are.

Mayer’s Cognitive Theory of Multimedia Learning

Richard Mayer has been researching how people learn with technology for almost 40 years (Mayer & Moreno, 1998; Mayer, 2002; Mayer & Mayer, 2005). His research has given us great insight into how people learn using computers and multimedia learning materials.

Please note that many Instructional or eLearning Design videos you’ll find online may be geared towards the creation of video courses – like self paced lists of videos that call themselves ‘Online courses’, including “how to make money with your online course”. This has been a growing trend in the last few years, so just be aware that these may not be the best source of information for research-informed practices.

Cognitive Load Theory (CLT)

Cognitive Load Theory was developed by Dr. John Sweller at the University of New South Wales in the 1980s (Chandler & Sweller, 1991; Sweller et al., 2011 ). Many of the instructional effects found through CLT research mirror findings of Mayer’s – they have have a slightly different way of framing them. CLT is all about how the design of instructional materials and strategies affect the memory of learners in tradition or technology-enabled scenarios. Mayer has the Split Attention Principle, CLT has a Split Attention Effect. The former is usually described in terms of how to it can improve learning, whereas CLT frame it how it can improve learning through cognitive processes. For more details on the practice applications of specific Cognitive Load Theory effects see What is the process for designing an experience?

If you’d like to know more about CLT, check out this guide on CLT in practice by the NSW Dept of Education.

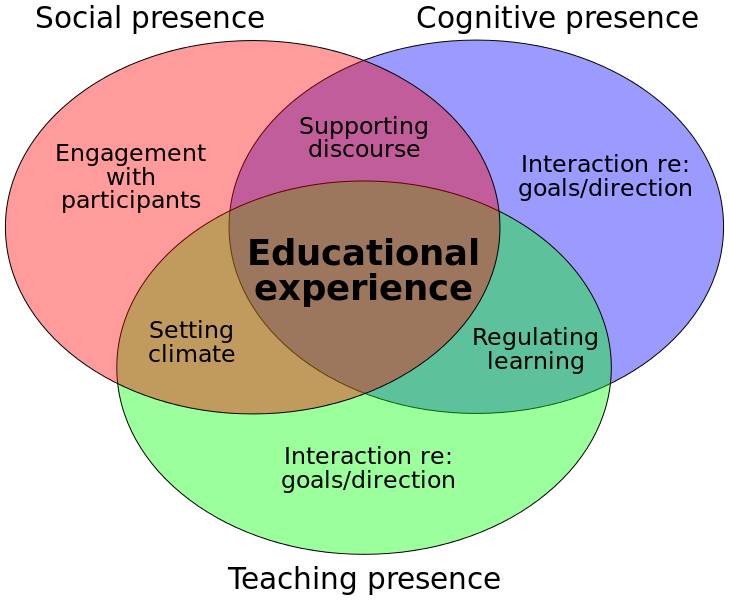

Community of Inquiry Framework (CoI)

The CoI framework was developed by Garrison, Anderson and Archer in 2000 and speaks to how people interact and engage in a technology-enabled or online learning environment.

It establishes 3 types of ‘presence’ that occur online.

Social Presence refers to the sense that learners have of being a part of a community and how a learning experience is designed to facilitate their membership in this community.

Cognitive Presence refers to how students interact with what they are learning – including learning materials, their own goals and learning processes including project planning, making connections and clarifying novel concepts and ideas.

Teaching Presence simply refers to how a teacher engages as a part of an online community and the strategies used to establish and persist a community over time.

For more, visit Athabasca University’s page on CoI.

Considering the Needs of our Learners

As part of the Analyse phase of ADDIE, mentioned above, the first step in designing any learning experience is to consider the needs of our learners. This can come in many forms and be done through a variety of different lenses.

“Characteristics of Online Learners”: A Disclaimer

Before we start, it’s important to consider the role that some past research findings may play in reinforcing damaging biases that exist, that could potentially harm our students. Over the years there have been many studies on ‘who online learners are’ (e.g., Part 1 of Stavredes), however given the changes in technology-enabled and online learning in recent years, as well as the changes brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic, it is definitely not appropriate to assume these statistics are still true, as it would be irresponsible to generalise from a study conducted 20 years ago to our own students. It is also important to consider given that technology allows cultural and language barriers to be broken down that any previous studies on ‘internationalisation of online learning’ (e.g., Bates, 2001) be taken with a massive grain of salt. Such studies may result in the generalisation of student populations, reinforcing biases, and even propagating and persisting deficit-mindsets and stereotypes among certain populations of educators. While it’s true that diversity amongst learners based on where we grew up or went to school previously may inform who we are as learners, including our motivations or how we engage in our learning experiences, it’s important that we design learning experiences that support and engage everyone, not just the dominant culture of our organisation or our own cultural sphere.

In terms of culture, Stravredes (2011) draws upon the work of Hofstede (2008) and Hofstede and Bond (1984). In the latter article the authors assert that learners who have grown up in diverse cultures may view education and its processes in different ways, and even outline which countries lean in specific ways. As the world and the diversity within it has changed in the last 37 years, it may no longer be appropriate to generalise in this way, however their work does outline some different ways to think about cultural norms and how students may or may not perceive their experience and relationships:

- Power Distance: What is the hierarchical and authoritarian separation between teacher and student? Is it a great distance with greater respect being shown to the teachers, almost seeing them as infallible and a source of all knowledge and students being perceived as low, or it it closer with teachers been seen more as fallible guiding peers?

- Uncertainty Avoidance: This refers to tolerance for ambiguity, when students may not be comfortable with not knowing the answers or not being ‘spoon fed’ instructions.

- Individualism / Collectivism: Depending on where we grow up, we have different perceptions of how we interact with others. Do we go it alone and pride ourselves on our individual accomplishments, or do we understand that we exist in a community and place respect and empathy for others in the way we approach working groups?

- Gender (and Identity): Unfortunately there are also differences in how respect is paid based on who people are, for both teachers and students. We need to be particularly mindful of this, given that racial and gender bias differs based on where we grew up.

It’s important to consider the above factors as we embed inclusive practices in our learning experiences and how our own experiences as educators have framed how we view students. For example, the fact that student behaviour and perceptions will differ even within the dominant culture between Australia and the UK, and even more-so between Australia and the United States, is something we may have not considered before.

Taking these factors into account, a growing trend within teaching practice is to pay attention to expectations both for the work done by students and the culture of each class. For example, if you wan to reduce power distance and have a more informal learning experience for the students, using strong, authoritarian language, referring to all your professional accomplishments and wearing business attire may not be the way to go. Being mindful of the culture we’d like to establish within our learning experiences and modelling this culture is a very important step to ensuring students are comfortable, encouraged to learn in effective ways, while also remaining respectful of everyone involved.

So, with that out of the way…let’s stay local – most educators already know their learners, they know who they are, what works for them and what doesn’t. If you’d like to explore the literature, feel free to start with a Google Scholar search and expand from there, or see if you can find some data or reports from your own context, behind mindful that the older the data, the less reliable it might be.

The most basic way to think about learner needs is based on the gap between what they know, and what they should know at the end of your learning experience. Importantly, we need to account for what they already know, if we consider the design of a learning experience for them, build upon the concepts of schema and constructivism. This can inform what learning objectives are written and how.

Another aspect to think about is more affective goals that learners may have, and this ties into their lifestyle, how they may wish to learn and perhaps constrained by how your organisation wishes them to learn.

Another useful way to think about the needs of our learners is to consider their strengths as learners. How can we capitalise on those strengths so that technology and pedagogy can excite them and engage them in their learning process?

Other points to consider are:

- Location

- What they ‘do’ (e.g., full time student, part time student, work full time, family responsibilites, etc.)

- Confidence with general technologies (e.g., web searching) and specific technologies (e.g., Microsoft Excel)

- What they already know

- What they can already do

- Their perception of the instructor

- Their perception of themselves as learners

- Different ways of expression

- Different ways of interacting with the world (e.g., introverted or extroverted)

- What different abilities they have

- How many languages they speak

For more on who our learners are from an access and inclusion perspective, feel free to check out Who are our learners? in the book Access, Inclusion, and Learning Technology

The ‘F’ word

As children, we play games in class, we run around and laugh, and by the time we get to university or a company’s training program, the quantity of this emotional experience is very much reduced. When considering how we learn, an incredibly powerful reinforcement within our brains is that of emotion (see DeLoux, 1994 for more). Emotions strongly reinforce memories, whether they be fear-induced, happy memories or another powerful emotional experience, those memories stick out for us and become ‘etched in our brains’ for a long period of time.

As memory is inextricably linked to our understanding of learning and how we learn it stands to reason that learning experiences that involve emotion are ones that will stick, whereas reading a particularly boring chapter of a textbook or journal article may not.

While it would be incredibly unethical to purposefully induce fear in our learners for the sake of enhancing their learning, more positive emotional experiences can accomplish a similar goal. So we need to talk the ‘F’ word in education – FUN. If learners can experience joy or emotional connection to other learners, this is great, and if they can have fun learning, this is even better. This approach usually involves making a game out of learning, so if you’d like to learn more, check out What are the Emerging Trends in Pedagogy?

Key Take-Aways

- Learning is based on prior experience and understanding

- There are different learning theories based on research that we can draw upon to help us frame how to teach, learn and design learning experiences.

- Historically different learning modalities separated Online, Face-to-face, and Blended/Hybrid, but in recent years these distinctions have gotten a bit more nuanced.

- Mayer’s Theory of Multimedia Learning, Cognitive Load Theory and the Community of Inquiry framework, all provide different ways to think about how we learn using technology

- The first step in designing a learning experience is to consider our learners in our immediate and local contexts.

Closing Questions

Before considering these questions, have a think about how to answer the question that this chapter poses. Feel free to share with a friend, colleague or family member and try to explain so that a novice would understand. If you don’t feel comfortable doing that, just say out loud “Humans Learn with technology…” and see where you go.

- Of the learning theories you read about, which ones would you classify as instructor-centred or student centred?

- What modalities are the most common learning modalities in your organisation?

- You’ve probably learned with technology for a few years now – what principles related to multimedia and online learning have you experienced or seen before?

Conclusion / Next Steps

Now that you know a little bit about how people learn, how they learn with technology and the landscape of how people learn using technology, the next chapter will look at technology in depth, thinking about the functionality and uses for different technologies for learning and what makes them effective in the support of student learning.

References

Bates, T. (2001). International distance education: Cultural and ethical issues. Distance Education, 22(1), 122-136. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.une.edu.au/scholarly-journals/international-distance-education-cultural-ethical/docview/217778045/se-2?accountid=17227

Beatty, B. J. (2019). Hybrid-Flexible Course Design (1st ed.). EdTech Books. https://edtechbooks.org/hyflex

Bjork, E. L., & Bjork, R. A. (2011). Making things hard on yourself, but in a good way: Creating desirable difficulties to enhance learning. Psychology and the real world: Essays illustrating fundamental contributions to society, 2(59-68)

Chandler, P., & Sweller, J. (1991). Cognitive load theory and the format of instruction. Cognition and instruction, 8(4), 293-332.

Irvine, V., Code, J., & Richards, L. (2013). Realigning Higher Education for the 21st Century Learner through Multi-Access Learning. Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, 9(2), 172.

Downes, S. (2005). An introduction to connective knowledge.

Kirkness, V. J., & Barnhardt, R. (1991). First Nations and higher education: The four R’s—Respect, relevance, reciprocity, responsibility. Journal of American Indian Education, 1-15.

LeDoux, J. E. (1994). Emotion, memory and the brain. Scientific American, 270(6), 50-57.

Mayer, R. E., & Moreno, R. (1998). A cognitive theory of multimedia learning: Implications for design principles. Journal of educational psychology, 91(2), 358-368.

Mayer, R. E. (2002). Multimedia learning. In Psychology of learning and motivation (Vol. 41, pp. 85-139). Academic Press.

Mayer, R., & Mayer, R. E. (Eds.). (2005). The Cambridge handbook of multimedia learning. Cambridge university press.

O’regan, K. (2003). Emotion and e-learning. Journal of Asynchronous learning networks, 7(3), 78-92.

Papert, S., & Harel, I. (1991). Situating constructionism. Constructionism, 36(2), 1-11.

Siemens, G. (2005). Connectivism: A learning theory for the digital age. International Journal of Instructional Technology and Distance Learning, 2(1). Retrieved from http://www.itdl.org/

Stavredes, T. (2011). Effective online teaching. Jossey-Bass.

Sweller, J., Ayres, P., & Kalyuga, S. (2011). Cognitive Load Theory (Vol. 1). Springer Science & Business Media.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1967). Play and its role in the mental development of the child. Soviet psychology, 5(3), 6-18.

Yunkaporta, T. (2009). Aboriginal pedagogies at the cultural interface (Doctoral dissertation, James Cook University).

Further Reading (optional)

Ertmer, P. A., & Newby, T. J. (1993). Behaviorism, cognitivism, constructivism: Comparing critical features from an instructional design perspective. Performance improvement quarterly, 6(4), 50-72.

Guri-Rosenblit, S., & Gros, B. (2011). E-Learning: Confusing terminology, research gaps and inherent challenges. International Journal of E-Learning & Distance Education, 25(1).

Ilgaz, H., & Gülbahar, Y. (2015). A snapshot of online learners: e-Readiness, e-Satisfaction and expectations. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 16(2), 171-187.

Kanuka, H. (2006). Instructional Design and eLearning: A Discussion of Pedagogical Content Knowledge as a Missing Construct. E-Journal of Instructional Science and Technology, 9(2), n2.

Hannafin, M., Hannafin, K. & Land, S. (1997). Grounded Practice and the Design of Constructivist Learning Environments. Educational Technology Research and Development, 45(3) , 101-117.

Hofstede, G. (May 8, 2008). Cultural differences in teaching and learning. FUHU conference on Education and Training in the Multicultural Classroom, Copenhagen.

Hofstede, G., & Bond, M. H. (1984). Hofstede’s culture dimensions: An independent validation using Rokeach’s value survey. Journal of cross-cultural psychology, 15(4), 417-433.

Soto, V. (2013). Which instructional design models are educators using to design virtual world instruction. Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, 9(3), 364-75.

Bajwa, I., Farooq, A., & Khan, A. (2010). An Effective eLearning System for Teaching the Fundamentals of Computing and Programming. International Journal of Multidisciplinary Sciences and Engineering, 1(1).

Moran, B. (2011). Valuing eLearning. Training and Development in Australia,38(4), 34.

Did this chapter help you learn?

94% of 33 voters found this helpful.

Provide Feedback on this Chapter