Implementing Technology in Practice

Overview

Now that we’ve explored and identified needs or problems to be solved, it’s time to think about how we might go about implementing some sort of change that would address them. In this chapter, a lot will be covered that may or may not be currently in practice in many workplaces, however they are important to consider if and when it comes time to implement a new technology.

As you’re reading through this chapter, some of the material may not be 100% relevant to you, so feel free to skip over and read what is most intersting.

Learning Outcomes

- Consider the different purposes for technology use in education (T&L, Administrative, and everything in between)

- Understand key factors in the evaluation, selection, and adoption of technology

- Understand different processes in selecting new tools based on requirements of your workplace / learning context.

- Understand managerial aspects of implementing new technologies and practices

- Critique current trends in your field (technology or otherwise), and how leaders currently approach their proliferation

- Consider how to sustain the use of this technology

- Identify groups of interested parties in this process.

Why is this important?

The steps between getting a feel for the needs of your organisation in terms of educational / learning technology and having that technology up and running with everyone happy and using it are many. Considering everything that needs to happen between these two steps is very important, and while this may take different forms within different organisations, what is covered in this chapter are quite common practices that may go by different names or vary in application. Having an understanding of these considerations will help you to think more critically about choosing and adopting new technology.

Guiding Questions

As you’re reading through these materials, please consider the following questions, and take notes to ensure you understand their answers as you go.

- What do you need to think about when implementing new technologies in educational settings?

- Who needs to be involved and how easy is this process?

- Once the technology has been rolled out, is there anything you or others need to do?

Key Readings

Vatanartiran, S., & Karadeniz, S. (2015). A needs analysis for technology integration plan: Challenges and needs of teachers. Contemporary Educational Technology, 6(3), 206-220.

Bates, A. W. (2015). Teaching in a digital age: Guidelines for designing teaching and learning. Retrieved from https://opentextbc.ca/teachinginadigitalage/ – For this one check out Ch1, Ch6, and Ch8 and read whatever you’re interested in as it relates to implementation.

Considerations before Selection

Think about Need

Much like any project management or even instructional / learning design practice, we must first consider the need we are hoping to fill by implementing a new technology. Why do we want to implement a new or updated technology? Does it fill a need that isn’t being met? Does it improve practices related to administration or teaching and learning in some way? How? What does this technology do to enhance our work and our outcomes? How does it push our organisation or our practice forward?

Think about Purpose

Educational contexts are not primarily about teaching and learning. While this is one of the primary reasons for many institutions to exist, the technologies we use many times serve other purposes, that include both teaching and learning and administrative tasks. Administrative technologies form the backbone of how many organisations operate, allowing employees to communicate, share files and perform other tasks.

While there can be some overlap in what technologies (hardware and software) can be used for both teaching and learning purposes and for administrative purposes, its important to consider the distinction or lack-thereof for the technology involved. Sometimes we may choose a technology for implementation to serve a very specific need, and find out that another tool may do exactly the same thing, or the tool we have chosen may actually disrupt operations in another area entirely.

Think about Timing

Most organisations operate on a specific schedule, whether it’s the academic school year in primary and secondary settings, or a specific training schedule in the military or responding to needs of clients in the corporate sector, the ways in which we implement technology usually need to adhere to the needs of those using the technology.

As part of implementing new educational technologies, we need to plan the timing of our implementation to make sure it happens at the most appropriate time. In a later chapter we’ll look at specific strategies to go about this, but for now, it’s useful to think in a ‘backwards design’ model, thinking about when the technology should be ready to be used, by who and at what level. Many technology implementations go through different phases, starting at small group pilots (see below) all the way to 100% use across the organisation. When all of this occurs is all part of planning the implementation.

Timing is also something we need to consider in terms of what we already have to work with – in some situations it may be a ‘cart before the horse’ situation – selecting and implementing technologies without considering a broader technology ecosystem or cultural context.

Think about scale

Depending on the needs we’ve identified or the problem we’d like to solve, this can happen at different scales. It might be implementing something across a few classes at one school or it might be rolling out software and hardware to thousands of students across multiple campuses of the same institution. Whatever the scale, it is important to consider what types of tools are out there and the level of consideration we need to give each.

Typically, the larger the scale of the project, the more money is involved and the more people as well. With higher stakes in the use of these technologies, they usually require more scrutiny and review before adoption and implementation can move forward.

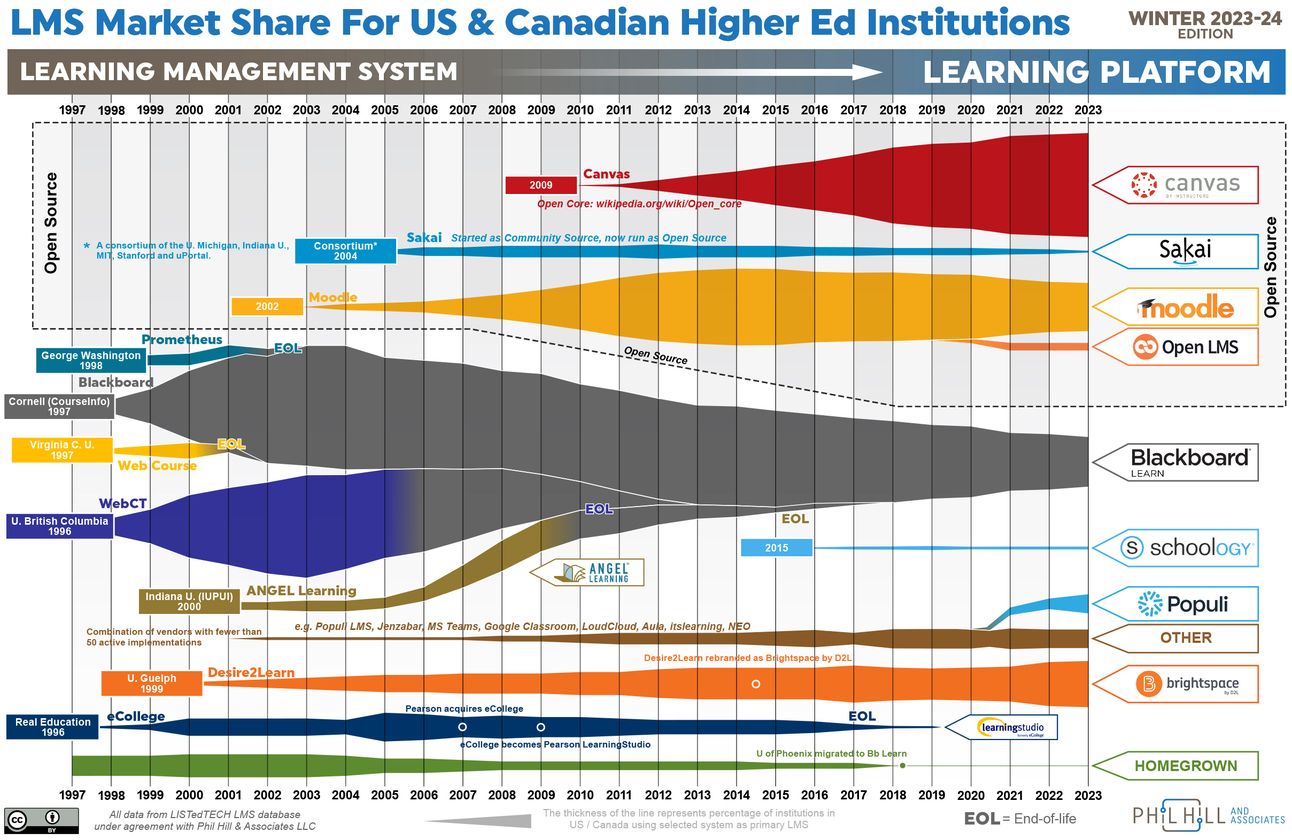

The diagram below shows the change in Learning Management System (LMS) market share over the 20+ years. For this type of technology, this is usually large scale, requiring a large budget and longer time commitment, so the number of options are quite limited as the market is quite saturated. For smaller-scale technologies that have more limited functionality and smaller scope (e.g, online flash card tool or student response system) there are usually going to be many more options and these generally don’t have a large cost associated with them. Additionally technologies that support smaller scale needs (e.g., delivering content, engaging students in a single class session) are usually faster to implement and easier to adopt more widely. For this reason, its important to consider the scale of our project so that we understand how different implementations may look.

Think about what others are doing

It’s also useful to do a ‘market scan’ of similar educational institutions to see what they’re up to. This can involve simply visiting a website, or even reaching out to staff or colleagues you know to find out what they’re doing. This is a useful exercise to benchmark technology use and practices across the sector to ensure that when considering different technologies for different uses, that these choices are being made in alignment with trends amongst collaborators, or competitors.

Selecting and Evaluating Technologies

Who will this affect and what short term and long term issues may arise?

Tony Bates’ SECTIONS Model (2015), while often applied in single classroom contexts, can also apply at different scales, and is definitely useful to consider factors involved in the selection of educational technologies. For more on this model visit What makes technology good for learning? in the book, Introduction to Learning Technology.

Ad-hoc use of Technology

Part of being a teacher is to improvise and adapt, and this is also true when it comes to technology. If we want to try something new in our face-to-face or online classes, we can often just use technologies that are available to us, whether paid or free. This practice could range from simply sourcing a Youtube Video we want to use, or to use Padlet or a similar tool to encourage student collaboration using a digital means. While this is a common practice, this is usually done by individuals on an ad-hoc, as-needed basis, with little coordination or leadership required. While this is definitely a legitimate and common means to adopt technology for teaching and learning purposes, this is not really the focus of this chapter, nor this book, so let’s focus on large (but sometimes still small) technology implementations.

Small Scale Pilot Projects

Before any technology innovation can occur, there needs to be an established mechanism to respond to the needs of end users (like teachers, students and employees). Without such a mechanism, it’s possible that the only avenue to innovate and adopt new technologies is in hands of leadership, and this top-down approach can lead to stagnation both in terms of technologies and practices. In the teaching and learning space, it can even lead to stagnation in pedagogical innovation, thus leading to the organisation falling behind others.

It should be noted that Pilot Projects are a more formal process for exploring new technologies and implementing new ways of working. There are other avenues for doing this work, such as establishing Communities of Practice (CoPs), informal user groups and other informal mechanisms – sometimes these groups even include students (and really should). Through these same groups, edtech leaders can get a feel for the needs of their staff and implement changes taking other perspectives into account. Now, back to pilots!

Pilot projects are typically small in scale. For example, the implementation of a new LMS is typically done through a different process, whereas smaller technologies, such as those that sit outside a large-scale implementation, or integrate into such an implementation are the target for pilots.

A pilot process is important in allowing those doing the work ‘on the ground’ to raise ideas to leaders for exploration, and testing. In a nutshel a pilot, is usually just a ‘test run’ of doing something new. In the edtech space, this can be a new practice using existing technologies or the use of a new technology entirely.

Pilot Projects have their root in pilot studies, a form of research that focuses on the small-scale testing of new practices (including technology or not). Many research studies in the edtech space take the form of pilot studies, so feel free to check some out to get an idea of how they work.

What pilots look like and how they are run will differ from organisation to organisation, but an example can look like this:

- At any given time increment (every 6 months or 1 year), employees, teachers or even students are given the opportunity to write / create a proposal for something they want to pilot – think of it like an ‘application for innovation’. Typically these applications have to justify the use of a new technology and speak to how it enhances teaching and learning beyond what it currently looks like. As mentioned above, it might even have to address how the proposal differs from what already exists if a similar technology is already in use.

- At this point, edtech leaders look at all the applications and have them reviewed, deciding on which projects have the most promise and which ones can enhance teaching and learning or administration in the best way possible.

- From here, the original authors of the proposal work with edtech leaders and their staff to map out how the pilot project will run, including any number of evaluations, steps and procedures to ensure a successful test of the technology in use.

- From here the technology is rolled out on a small scale (as this is a test after all), and those using the technology are typically asked how it went through surveys and other evaluation mechanisms which may include usage and learning analytics, etc.

- The results of this research / evaluation is then examined for opportunities and barriers, considering them for wider adoption, financial viability and other considerations in change management for the organisation.

- If all goes well, the technology will be adopted at a larger scale, with more financial and human resources put in place. If the pilot doesn’t accomplish what it intends to, or its not financially viable, the pilot will end and the technology will be ‘sun-setted’, meaning it will be allowed to lapse in implementation and be decommissioned.

Pilot projects do require resources to even exist. They require time, energy and funding for those working in the educational technology space. Some organisations may only have enough resources for maintenance and support, while others may not consider this mechanism for innovation to be a priority. For organisations that do have a formal pilot process established, the work has to be earmarked and dedicated as part of workload and human and materials resources need to be invested.

As Rob Peregoodoff, an edtech leader based in Vancouver suggests, support for pilots and a mindset of leading others with the assumption that change is a part of institutional culture is integral to educational innovation.

There are many variations in how Pilot processes can be run. Some may be based on grant project funding that asks for expressions of interested in a predetermined practice or technology. Others may be general in application and provide small funding opportunities for employees to explore new technologies. In these instances, projects may be more ‘ad-hoc’ in nature and not built into the culture of the organisation.

If you’d like to check out an example evaluation report from a Pilot Project, see this Mattermost Project Report. Mattermost is a team chat tool, similar to Slack or Discord. For more about the process this project went through, check out the University of British Columbia’s pilot process documentation.

Large Scale Implementations

Requests for Information and Proposals (RFIs and RFPs)

For larger-scale implementations (such as an LMS/VLE or communication platform), selection and implementation of technologies are usually in the hands of leadership and other groups of individuals selected by leadership, such as a committee or user group that has been selected or self-identified as beneficial for the project.

In these such cases, with few options in the marketplace for specific technologies to be used the choice between these technologies has to be systematically evaluated through a pipeline that helps selection committees / groups make the best decision they can.

First, the project to adopt or adapt a new technology is announced (usually publicly) at the organisation and select companies are invited to provide their initial ‘pitch’ in the form of response to a Request for Information (RFI). As this is usually done publicly, those not on the list are also free to submit information to the organisation to register their interest as a potential vendor or supplier. An RFI is usually quite general, with the company describing its space in the marketplace, it’s key features and what sets in apart from the rest of the industry.

In some cases, the organisation and the committees involved know exactly what they want so then put out an RFQ -Request for Quote – jumping to the final step of procurement.

In many cases though, after companies have responded with information, the parties involved at the organisation will review all the submissions. Some may be removed from the list, while others progress to a Request for Proposals (RFP).

An RFP is all about getting as much information as you can to make the best decision possible. When it comes to edtech RFPs, these usually involve the organisation providing a details list of needs and wants to the companies, so they can respond specifically about how their solution is the best one. Often, companies will also provide live demos or give demo access to the tools for users to try out.

After RFP submissions have been received by the organisation, sometimes feedback is also gathered from other emploees or users. For example, in the case of an LMS / VLE selection, a larger pool of instructors are usually asked to engage with demo access to the platform and asked to evaluate it based on specific criteria, such as ease of use, responsiveness, and other factors.

Based on this evaluation and the organisations response to each RFP submission, a decision is often made to reduce the potential solutions to two or three finalists, at which point an RFQ can go out and the process for ‘getting’ and implementing the technology begins.

Privacy Impact Assessments (PIA)

As part of the selection of technology both for small and large scale solutions, it’s very common to perform a Privacy Impact Assessment, especially when students are involved. Many countries now have legislation in place to ensure student information and educational data is protected, so a PIA is done to ensure that any 3rd party technologies conform to this legislation, and protect student privacy through appropriate storage and data collection measures.

PIAs are typically done through a template or rubric system, with staff going through a document to respond to security / privacy issues one by one, resulting in a PIA report.

If you’d like to check out some examples of PIAs, feel free to explore UBC (Canada) and their Privacy Matters site, including Proctorio, an online exam proctoring software.

Additionally, the Australian Government’s Guide to undertaking privacy impact assessments is a great resource.

As Educational Technology Ethics is a growing movement in the area, PIAs are also starting to think more proactively, by not just evaluating a technology based on legislation and the technical aspects of student privacy, but on the ethical practices of the company in how it may collect, store and use the information it gets from students.

Access and Inclusion Assessments

Though not as common as PIAs, some organisation also choose to conduct Access and Inclusion assessments to ensure that technologies chosen address the needs of all learners and ensure that biases that may exist in society are not propagated further. As part of an RFP or RFI, organisations may ask the companies responding to speak to how their technology supports learners with different abilities and conform to web accessibility standards.

Additionally, given that a few prominent educational technologies have been found to be racially biased, an evaluation of how a technology can ensure inclusion and celebrate diversity, while not disenfranchising students may also be conducted.

Ecosystem Integration and Standards

As we all know, most technologies in educational settings do not exist in isolation. Many systems must be integrated with each other, allowing them to exchange information, allow teachers, students and staff to log in using one credential, and to ensure that this is all as seamless an experience as possible. This concept is usually referred to as an Ecosystem, or a learning technology, educational technology, learning systems…ecosystem – take your pick in terminology 😉

Given that different systems may manage communication, student enrolment, student learning, grading / marking, and many other separate but related tasks, the selection of a technology should also be evaluated in how it can integrate into this ecosystem. Depending on the scale of the project this integration may differ in terms of priority in evaluating a new technology. If the ecosystem is small or if the project doesn’t need to be integrated, that makes things easier, but if the project or ecosystem is large, then integration between systems is almost a requirement. This can also have implications for how data itself is managed, and can affect Data Governance as well, the formal process for establishing standards for how data is stored.

On a related note on the Data Governance side, we also need to consider any Learning Analytics projects that might be in place at our organisations. If there is an effort to leverage educational data, we need to think about how the technology we’re implementing can be integrated into this project, including what data it collects, how it collects it, who has access, etc.

Further still, there may be legislative requirements that certain technologies need to conform to in order to be adopted in the education sector. In the private sector, some technologies may be more relaxed about data privacy and storage, but in education, this is usually more important, and different sectors can have different levels of requirements in terms of how technology is used, such as those in health care education, military or schools, depending on who the students are, what the aim of the institution is, and how it delivers its learning experiences.

Terms you may need to know for this work are:

- SIS: Student Information System is a system that houses all student names, contact and demographic data, which is then pushed in to sync names and other information with other learning platforms

- Federated Login or SSO (Single Sign-on) is a mechanism whereby users only need one user login to access all technologies at their institution

- Interoperability refers to a technology’s ability to integrate and ‘talk to’ other systems out of the box. Examples of interoperability include the SCORM standard (Shareable Content Object Reference Model) for creating digital lessons, and LTI (Learning Technology Integration) which is a standard for creating other tools that will share information between the tool and an LMS.

Who Should be involved?

When implementing new technologies in educational settings, it’s really important to engage with parties who can assist in the use of the tech and to support its implementation. This can very greatly based on the workplace or learning context, but ensuring that we work with everyone who may end up using and supporting the technology at different levels is important to consider.

Consider enlisting help from all levels from management, to teaching and learning staff and support staff. Given that all these different people have different responsibilites and insights and expertise, it’s valuable to include them in the process, to meet with them and discuss their thoughts on the implementation process and what their role can be in it. An added benefit of doing this is that we can delegate tasks associated with our implementation to those who would be most appropriate to fulfil these tasks, ranging from gather feedback from others, setting up professional learning and training (e.g., workshops and tutorials), and even day to day support of the technology once it’s been implemented.

Sustainment of New Technology

Another consideration we need to make is the longevity and sustainability of a technology we are interested in. With established technologies and companies that have been around for years, we may have already used these tools, or many know many colleagues who have used them. Sometimes, how long a technology has been around can be a good thing, and it can also be a bad thing. In the edtech sector, some tools have been around for years, and may become stuck and unable to redesign, redevelop or keep up with the times, whereas others are able to do so. Some companies work closely with their clients, building in new features and updating old ones to meet future needs and ensure sustainability, while others do not.

This responsiveness and the ability to change with the times is also an important aspect of a technology to consider when selecting and implementing technology – not just what it can do now or in the future, but what it has done in the past and how it has changed over time. If it hasn’t changed that much over time, we might need to think twice, but if it started out many years ago and has stayed relevant and fresh, then it’s worth a look. Tied to this, is the update cycle of a technology. In a world where we get App updates pushed automatically to our devices once or twice a week, if not more often, a technology that provides updates once a year, may not be as responsive to our institutions needs as we need it to be.

Thinking Critically about Trends

As with many other fields, it seems like there is a new ‘thing’ that can solve all of our problems in one foul swoop. In the Educational Technology space, this is also true, and there are many tools and companies vying for our attention as educational leaders.

It’s important then, to be mindful of how technology is presented and selected for use in our educational settings, and to think about the trends that we may see, the technologies we’re exposed to and how they may work in practice. There are many events or conferences we may attend that showcase a specific technology or solution that looks like it would be the best thing ever, so it’s important to slow down and consider everything we’ve read about in this chapter before jumping all-in.

When selecting new technologies, most of the time we look for longevity, both in the marketplace, and in the potential longevity of the technology or tool itself. Most educational leaders won’t invest everything in the newest technology, but will take a more measured approach.

Virtual Reality (VR) is a good example in this area. VR is a relatively new technology, with incredibly exciting potential for use in education, though we still don’t know enough about it to make it viable and ubiquitous in educational settings. Challenges with its implementation ranging from negative physiological effects such as dizziness and nausea to a lack of consensus in its ability to enhance teaching and learning in research mean that VR is a really exciting thing to explore (or pilot), but may not be ready for primetime.

Critically evaluating technologies is a key skill in the selection and implementation of technologies. Ultimately, we want these technologies to be used, and for our students, teachers and staff to delight in their use for years to come, so ensuring that we think twice about the newest bright and shiney thing, is an important part of ed tech leadership.

Key Take-Aways

- Whether technology selection is for teaching and learning purposes or for administrative purposes, the selection of technology at any scale requires thought, planning and careful evaluation.

- For small scale projects, pilots are a good way to test out a new technology to make sure it enhances teaching and learning before it is adopted wholesale.

- For larger scale projects, the process is much more systematic, meaning more steps and more areas for evaluation and examination, including RFIs, RFPs, PIAs, etc.

- Being mindful of the difference between established companies and their technologies compared with the ‘new kid on the block’ can help to make sure technology implementations go well.

Revisit Guiding Questions

How would you go about implementing a change in educational technology in your workplace or learning context?

Conclusion / Next Steps

Now that we know a bit more about all the factors involved in selecting and rolling out a new technology, in the next chapter we’ll discuss how we can support the implementation from the human side of things, including how we can support our colleagues in the use of new technologies.

References

Clarke, R. (2009). Privacy impact assessment: Its origins and development. Computer law & security review, 25(2), 123-135.

Did this chapter help you learn?

No one has voted on this resource yet.