How can we support others?

Overview

In previous chapters, we examined what leadership looks like in different contexts, as well as how educational technology can be implemented within these contexts. In this chapter we’ll explore the next step in this process – now that we have technology in place, how can we support its use by our colleagues.

Learning Outcomes

- Consider the support what peers and colleagues may need when new technologies become available

- Understand the key aspects of modelling and mentorship

- Ensure sustainment of use, including staff knowledge and induction

- Consider how peer-led professional development may compare to facilitator-led development

Why is this important?

With any new technology implementation, whether large or small scale, it’s important to consider how those who will be using the technology will be supported in their use of the technology, both from a technical standpoint, as well as a pedagogical or administrative one (depending on the technology).

Guiding Questions

As you’re reading through these materials, please consider the following questions, and take notes to ensure you understand their answers as you go.

- How do instructors in your sector usually engage in professional learning around educational technology? Is this the best way to deliver these experiences?

- What are some common barriers to offering or implementing these professional learning experiences?

- What do you see are the priorities when offering such experiences to ensure that technologies are adopted and used effectively?

Key Readings

Howard, S. K., Tondeur, J., Siddiq, F., & Scherer, R. (2021). Ready, set, go! Profiling teachers’ readiness for online teaching in secondary education. Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 30(1), 141–158. https://doi.org/10.1080/1475939X.2020.1839543EISSN: 1747-5139

Jones, E. T., Lindner, J. R., Murphy, T. H., & Dooley, K. E. (2002). Faculty philosophical position towards distance education: Competency, value, and educational technology support. Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration, 5(1), 1-10.

Liu, S. H., Tsai, H. C., & Huang, Y. T. (2015). Collaborative professional development of mentor teachers and pre-service teachers in relation to technology integration. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 18(3), 161-172.

Lloyd, M., & Cochrane, J. (2006). Celtic knots: Interweaving the elements of effective teacher professional development in ICT. Australian Educational Computing, 21(2), 16-19.

Learning, Professional Development and Professional Learning

Again, we run into terminology that varies across sectors and purposes. Learning itself can have many different meanings, motivations and methods, however when it comes to professional development and professional learning, these are usually engaged in within the context of continuing education when educators and professionals are already ‘on the job’. Some may argue that professional development is an older term, referring to more passive workshops that serve as an information dump, whereas professional learning is a much more robust, collaborative and transformational experience for teachers and professionals. According to the NSW Department of Education, the nature of professional learning is cyclical and continuing, meaning it is built into the culture of working in schools, to continually build skills. If we subscribe to this differentiation, then we can perhaps understand what is involved when we see these terms.

Liu and Phelps (2020) conducted a review of a large data set focused on teacher professional development experiences and found an number of interesting insights into the effectiveness of this type of learning. They found that the nature of the training affected how much information was retained. For example, when training is sustained over a longer period of time (e.g., a series of connected workshops instead of just one), retention of information and skills improved. Additionally, other researchers found that when professional development that was delivered during the summer break months resulted in lower retention compared to when they were offered during the school year.

What do our Teacher Learners need?

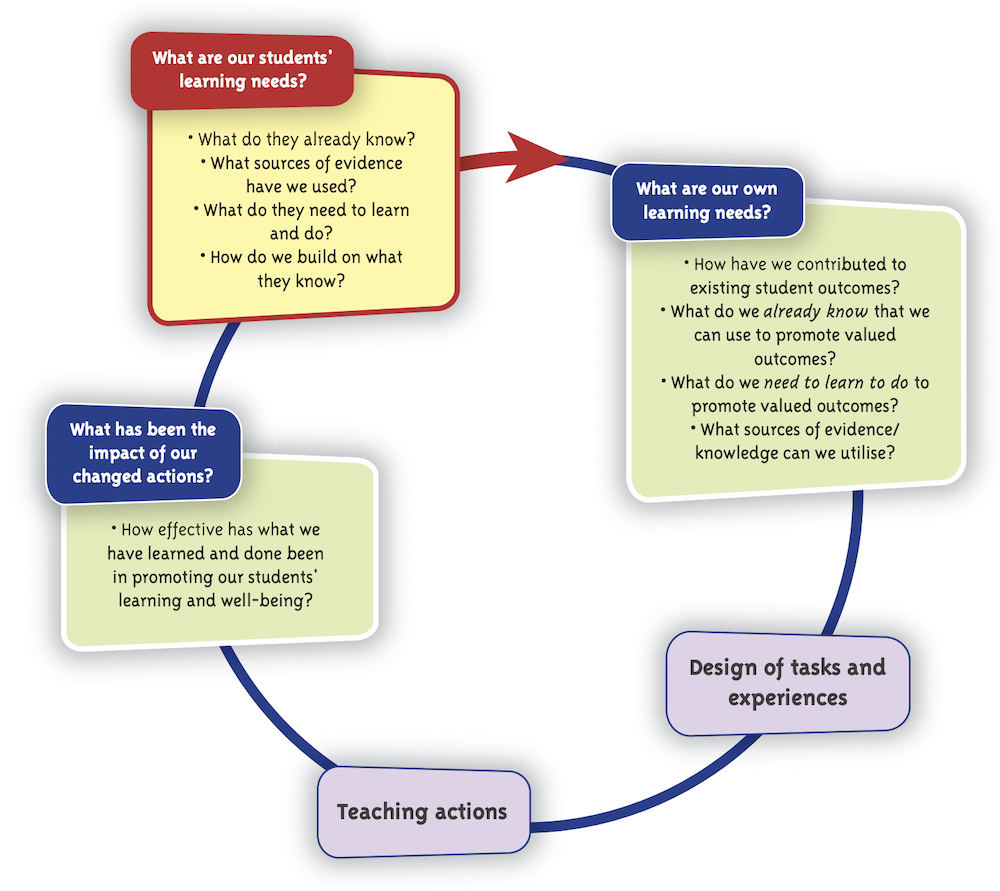

Much like when we develop learning experiences or lessons for our students in class, the same principles would apply when considering the needs of teachers as learners or professional staff as learners. We should look to what they already know about the topic, their existing expertise and experiences and build upon this to ensure skills, knowledge and abilities are built to incorporate new technologies when they are deployed. In these cases we can still think in terms of instructional or learning design models such as Backwards Design, ADDIE or any other that is appropriate for the context.

Motivation

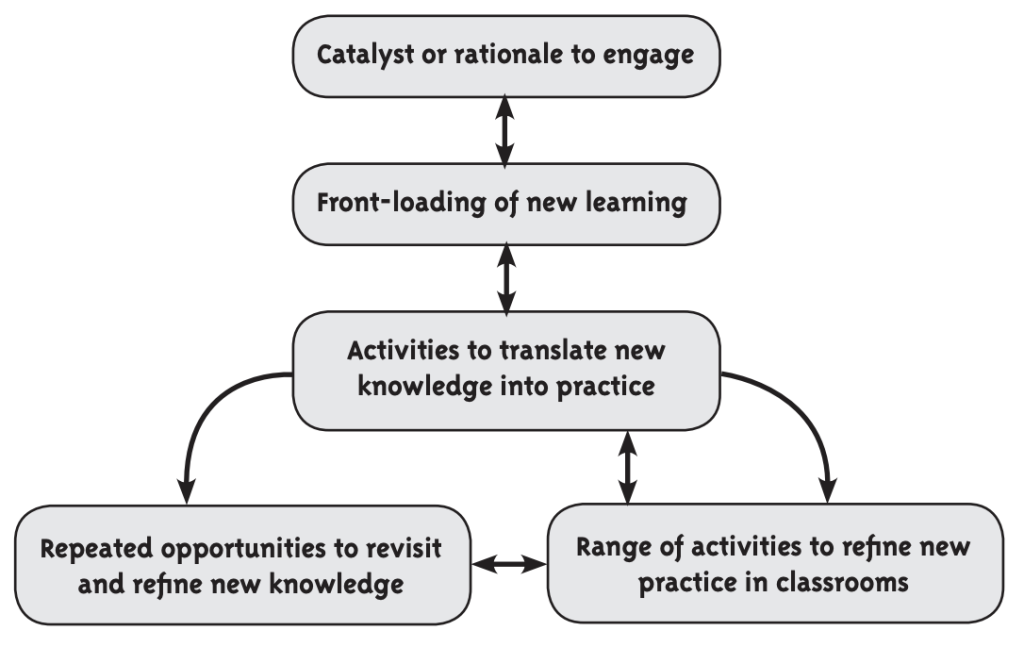

Why would teachers or professional staff engage in professional learning around technology? Temperly et al. (2007) outline how they may engage in professional learning and where their motivations might come from. This will obviously differ from place to place, however it’s important to think about what will actually motivate our teacher learners to engage in this sort of learning experience. Will the new technology improve teaching and learning? Is it clear how or why? Will it make the lives of teachers and professional staff easier, make the completion of repetitive tasks faster, or allow them to streamline workflows? Some teacher learners may be motivated by different factors, so keeping this in mind, and perhaps even being transparent about why professional learning is being offered might contribute to increasing motivation.

Professional Learning as part of Technology Implementation

When implementing new technologies for teaching and learning, or for administration purposes in educational workplaces, it’s important to consider how professional development will factor into each rollout. If technologies are implemented without a plan for supporting new users, the rollout can go very differently.

Technology and Pedagogy

When new technologies are introduced, there are a couple of different ways we can think about onboarding staff.

- Technical: This is essentially the button clicking – how the technology works and how to use it from a technical perspective. This usually takes the form of a software workshop or series of interative of static resources or tutorials housed online.

- Pedagogical: This is all about how to teach or use the technology for the intended purposes effectively (depending on the tool)

We may look at both of these as separate aspects of professional learning, for example offering a separate technical training, followed by a ‘how to teach’ training, but more often than not educators will want to understand the affordances of certain tools and how they’re used in practice, so its usually best to use an applied approach to ensure our teacher learners can use tools as they are intended, which means blending the technical with the pedagogical.

If we look at the diagram above which applies to teacher professional learning in general, it may look similar in terms of its cyclical nature and focus on reflection (evaluation), so can be interpreted as an adaptation of ADDIE, if you’re familiar with that model of designing instruction. If we extend this to think about technology, and how we can support others in the use of technologies that may be new to them, bringing everything back to the needs of learners is a good thing, so that those learning how to use technology can keep this at the forefront, as opposed to thinking about using ‘technology for technology’s sake’ and no ultimately in the service of improving learning outcomes for students.

Culture and Formality

Depending on the culture of your organisation, professional learning may look quite different. In some contexts, professional learning can be very structured with traditional workshops consisting of presentations and perhaps even quizzes, while others are less formal experiences, with demonstrations, sharing of ideas, question periods and collaborative brainstorming. There is no right or wrong way to engage in this work and it can be incredibly varied, but it should ideally be matched to the culture of the organisation where appropriate.

With that said, it may also be valuable to think about ‘changing things up’ and shift away from current practices to consider how such a shift may change culture and underlying practices around teaching and learning, especially with regards to the use of educational technologies.

Types of Support

Communication

When implementing any changes to technology in educational settings, communication is incredibly important. While the last thing we need sometimes is another email, conveying information about what is happening and why will help teachers and professional staff to understand any changes that are coming, why they are being considered and the effects it will have on how they work.

Communication strategies are thus an important part of any technology rollout, including what is shared, when it is shared, and who it is shared with. Obviously, sharing more information is always best, but sharing too much too often can also create confusion and anxiety amongst those who are expected to learn and use new technologies. As such a clear plan on communication is recommended for any technology rollout, and factors into change and project management as well (we’ll cover a little bit of this in the next chapter).

Workshops

The most common format for technology professional learning would be a workshop, either face-to-face or online. If we reflect back on the technical and/or pedagogical focus of how educators should be supported with new technologies, what we cover in and how we plan these workshops might be different, depending on the technology implementation we’re working on. We may even plan a series of workshops that work in a linear or cyclical fashion, moving from purely technical, all the way to peer-led discussions around the power of our new technologies to transform teaching and learning.

When considering how we may want to deliver workshops, we can consider where we offer them (in a classroom or online), and even perhaps what learning theory we want to align them with. For example, if all we want to achieve is to have learners click buttons and perform tasks, this may be more of a behaviourist focus, whereas if we want them problem solve to solve a task that is common for their own work, perhaps this will be more of a constructivist workshop.

Workshops (Chalk and Talk Presentations)

We’ve all experienced workshops that can be equated with a ‘death by PowerPoint’ whereby the facilitator conveys information, while the teacher learners sit back and passively absorb (or not) new information presented on the screen in the front of the room. While this format has its place in some circumstances, it really comes down to the value of the time dedicated to this format, as well as what information is being presented and how.

When we reflect on models of teaching and learning, including how people learn (see How do we Learn with Technology? for more) and how they learn using technology, this format may be more appropriate for an intentionally passive and self-paced format, such as an email, or shared presentation in which learners can take in the information in a manner that suits them.

Workshops(Active Learning )

Workshops that are more hands-on and active, especially when they’re related to the application of new knowledge and tied to clear end goals and outcomes, can be much more valuable. When new technologies are introduced, how the technologies are used to support teaching and learning or administrative tasks really ties into the time spent on the workshops and are usually considered more valuable than a Chalk and Talk style. When learners have the opportunity to practice using a new tool, to talk about how they imagine using the new tool or to be led through specific tasks from start to finish, they are able to see the value of the tool in a more meaningful way. Essentially, this type of workshop can draw upon existing active learning frameworks, as well as any innovative pedagogies that may be in the facilitators toolset (see What are the Emerging Trends in Pedagogy? for more).

- Let’s complete a common task

- Scavenger Hunt

- Race to complete tasks

- Q&A

Peer-led workshops

Another strategy that links to sustainability and mentorship is the idea that new technologies and the practices associated with their use can be shared amongst the teacher-learners themselves. For those in leadership positions or those in technology support positions (e.g., instructional designers / learning designers), these individuals may be somewhat distanced from everyday teaching and learning practice depending on their roles. A way to mitigate this makes learning of new technologies more relevant, and a way to build buy-in with the people who’ll be using these new technologies is to enlist the help of teachers to deliver workshops.

In university and other sectors, given that some support staff may not be in the same hierarchical ‘status’ as instructors, having a peer lead a workshop can build credibility for the new technology and provide an avenue for teachers to ask more questions and share ideas. As teachers may be unwilling to ask for help from someone who is not a teacher, this can encourage learning and community building around shared practice. Much like our students, teacher-learners may also not wish to appear less than proficient in something, and thus may be reluctant to ask for help, especially when it comes to the implementation of new technologies.

When in a leadership position focused on educational technology, it’s common to capitalise on those who are ‘willing tinkerers’, that is teachers who are always willing to wade in and try something new, regardless of their comfort level with it. These people are invaluable and are often referred to as ‘rock stars’, because they can be relied upon to help with implementation efforts and provide example uses for their colleagues and even to lead workshops to showcase how they’re using the new technology.

Online Learning Materials (Static / Self-serve)

A very common approach to educational technology professional learning or training is to simply put some resources online. These can take many forms, from step-by-step instructions on how to complete certain tasks, including screenshots or video tutorials. They great thing about these sorts of resources is that they’re always available, night or day, from any location and can serve as self-service reference materials for teachers and instructors who are confident enough to ‘go and look’ for solutions themselves. Sometimes called a Knowledge Base, one caveat to this approach is that these resources and how they are presented online and how easily they can be found will dictate how much they are used. As an exercise, pick an educational organisation in your sector and try to find information about a specific topic on technology enabled learning, and see what you can find.

Online Learning Materials (Interactive Lessons)

A companion to static reference materials or knowledge bases are actually step-through lessons that walk the user / teacher/ instructor through how to complete a task from start to finish. These are usually interactive in nature, either presenting a fully simulated software environment (like a virtual version of the real LMS or learning tool) or a dynamic lesson full of videos, images and even mini-games. The appeal of these tools is that they usually include some sort of assessment built in to ensure learners are meeting the goals of the lesson, thus are heavily used in training scenarios, such as corporate and workplace training. Sometimes these are even presented in sequence (or like episodes), leading to broader competency in the use of a tool (e.g., compose a new email > write the email > send the email). Advancements in technology, such as learning analytics and machine learning, are also leading to advances in this type of materials, making them ‘smarter’ and able to adapt to the needs of each learner, to result in more personalised experiences.

Example tools used to create such experiences include:

- Articulate suite of tools (360 and/or storyline)

- Adobe Captivate

Longevity of Materials

The challenge with certain types of online resources is that their planning and development usually takes more resources and time than that of static web-based materials, as there may be storyboarding, video capture, audio scripts, and audio recordings to develop as part of the singular resource. Having so many moving parts also means any changes to these sorts of resources means they are more cumbersome to update, as the workflow usually involves, gathering materials, collecting them all, adding activities / assessments, exporting and deploying the tutorial online somewhere. By comparison, a static web-based resource already exists where it lives, so can be edited in place (like on a blog site).

Training Wheels support

Many times if someone isn’t confident using technology, it may help to simply have someone around in case things go wrong. Engaging in workshops and other means of professional learning with regards to technology is one thing, and confidence may be high when working by oneself in the use of technology, but using it in front of students is a very different experience. On the spot, in front of 10, 50, or even 300 students can still be nerve-wracking for even the most confident instructors, so in some instances it’s helpful to offer to have someone attend the class as a guest to support should anything go wrong with the technology.

This strategy can be effective in building the instructor’s confidence, and can be used in a face to face classroom setting, or online, with the technology support staff just ‘hanging out’ should anything go awry. Resources are obviously something leaders need to think about, so this type of support is usually not an ongoing thing – support staff usually can’t show up to every class for every teacher, so we can think of it more as a scaffolding task. Support staff can join a few mins before class starts to make sure the teacher gets up and running. They can help them to run tests of the technology they’re using, then leave when everything is in its right place. Once the instructor is moving along, and sees that the technology is working as it should, their need for support will diminish and support can be withdrawn.

Communities of Practice

When people get together to share ideas as part of a community, this can be called a Community of Practice, or CoP. Many times, these structures can include formal or informal professional learning experiences, but can also just ‘exist’ in the form of an online community that allows members to share ideas, ask questions and be a part of a larger conversation. They can exist within a closed context (like a school or specific campus of a university) or they can be broader in scope, existing at a state, national or international level. If you’ve ever joined a Facebook group or Slack or Discord group that focuses on something specific in the professional world, this could be considered a CoP.

Communities of practice are focused on 3 shared elements (see Wenger, 2011):

- A domain – the shared interest across a group of people

- A community -activities, interactions that occur within a group of people

- A practice – member develop a shared repertoire of resources to support each others’ work

Putting it all together

Many professional learning experiences now take the form of a blend of many of the aforementioned approaches, with workshops, communities of practices and resources all mixed together to foster conversation and share ideas. A good example of a learning community is the T4L (Technology for Learning) initiative from the NSW Dept of Education. This includes a resource-based websites, almost weekly events focused on pedagogical use of new technologies, a podcast, as well as a Microsoft Teams site for teachers, where they can ask questions, and share ideas and resources. The team that runs this site is also active on social media, especially twitter, which is a highly used professional resource among teachers.

As King (2002) outlines, learning new technologies is inextricably linked to new opportunities for teaching and learning practices, and new ways of engaging students. This can be for many reasons, including how to meet specific state or national standards, or simply to reconsider how to teach a specific lesson. Whatever the outcome, learning how to use new technologies can serve as a catalyst for alternate ways of teaching and facilitating, so as long as this foundational principle is considered when planning professional learning experiences, progress may be made. It should also be noted that not everyone engaging in these experiences will pick it up immediately – in fact most may not, but through ongoing engagement in various professional learning experiences, new approaches to teaching and learning with the support of new technologies will slowly but surely transform practices in any context.

Sustainability

One important consideration when providing support in the introduction of new technologies is how these supports can be sustained and even perpetuated. Often, online resources may not actively sustain any efforts to train or support new users of a system, but they are a realiable means of reference. Communities of practice, including lunchtime ‘brown bag’ workshops and conversations can allow for a more self-sustainable activity, because they become learner-led, meaning those who are trying to learn the new practice or software will begin to help each other, as opposed to relying on a workshop facilitator or constantly refer to online resources. This can releive the burden on those responsible for development the training.

Modelling and Mentorship

A number of important studies over the years have explored how the pairing of practicing teachers and student teachers (teacher candidates) in a mentor – mentee relationship can support the acquisition of teacher knowledge when it comes to educational technology. Margerum-Leys and Marx (2000, 2002, 2004) conducted a number of studies and found that teacher candidates benefitted from the relationship with more experienced teachers, especially when it came to knowledge of technologies and how to apply them in teaching. Interestingly, this work focused on the acquisition of pedagogical content knowledge and technical knowledge, which formed precursor theorisation around the TPACK Model for technology integration.

From the findings of these studies and others like them, pairing novice teachers in the use of technology with those more experienced, can support the latter’s use of technology. In the case of implementing new technologies, however, this may be challenging as all teacher learners may be new to the technology.

Peer-led Professional Development

Teaching Squares

Prominent in North American tertiary contexts are something called Teaching Squares. Haave (2014) and Berenson (2017) outline how these can be used for a number of different peer-development purposes as a part of reflective practice in teaching and learning. Basically, it works by grouping four instructors from different disciplinary areas (let’s call them A,B,C and D). First they are paired up (A with B, C with D), and work together in these first pairs for a set amount of time, visiting each others’ classrooms and providing feedback and brainstorming. They can then make any changes to their practice they like, then they switch pairs (A with C, and B with D) to go through the process again. Then at the end they all meet as a group to talk about what they learned from each other and any new insights to their practice. This is just one example how teaching squares can be implemented. In the technology space, it can be used to highlight how a new technology is being used by all parties, including how they might think about, learn about and implement the technologies, with the idea being this structure is cyclical and repeatable over time.

Pandemic-informed Professional Learning

There is now a growing body of research (Al-Naabi, et al., 2021; Sumer, et al., 2021), focusing on how teachers and instructors adapted to something called ‘Emergency Remote Teaching’ at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. According to Hodges, et al. (2020) ERT:

“is a temporary shift of instructional delivery to an alternate delivery mode due to crisis circumstances. It involves the use of fully remote teaching solutions for instruction or education that would otherwise be delivered face-to-face or as blended or hybrid courses and that will return to that format once the crisis or emergency has abated”

Much of this research focuses on approaches to supporting instructors in the fast transition to teaching online, through methods such as reflection on practice as they transitioned, as well as the role that instructional design and support staff can play in such a transition, including leading workshops, providing forums for discussion amongst instructors as well as resources and funding to support such initiatives. As we continue to learn more about this transition, such strategies can help us to learn about professional learning strategies when timelines are less than ideal or when unforeseen events disrupt educational settings, thus requiring new means of delivering learning experiences.

Key Take-Aways

- Carefully consider the most appropriate means of providing support (i.e. the type of support) for your context

- When possible, engage with instructors to help implement and lead professional learning when educational technology is involved.

- When possible, use multiple approaches to

Revisit Guiding Questions

Now that you’ve learned a little bit about different approaches to thinking about supporting teachers as technology is implemented, what do you think would be the best approach in your context? Why?

References

Improving Teacher Professional Learning (AITSL)

Al-Naabi, I., Kelder, J. A., & Carr, A. (2021). Preparing teachers for emergency remote teaching: A professional development framework for teachers in higher education. Journal of University Teaching & Learning Practice, 18(5), 4.

Berenson, C. (2017). Teaching squares: Observe & reflect on teaching & learning.

H. Timperley, A. Wilson, H. Barrar & I. Fung (2007)Teacher Professional Learning and Development: Best Evidence Synthesis Iteration, Wellington, New Zealand: Ministry of Education. Retrieved from https://www.educationcounts.govt.nz/publications/series/2515/15341

Haave, N. (2014). Teaching squares: A teaching development tool. Teaching Professor, 28(1).

Hodges, C.B., Moore, S.L., Lockee, B.B., Trust, T., Bond, M.A. (2020, March 27). The difference between emergency remote teaching and online learning. EDUCAUSE Review. https://tinyurl.com/rekxcrq

Hodges, C. B., & Fowler, D. J. (2020). The COVID-19 crisis and faculty members in higher education: From emergency remote teaching to better teaching through reflection. International Journal of Multidisciplinary Perspectives In Higher Education, 5(1), 118-122. https://doi.org/10.32674/jimphe.v5i1.2507

King, K. P. (2002). Educational technology professional development as transformative learning opportunities. Computers & Education, 39(3), 283-297.

Liu, S., & Phelps, G. (2020). Does teacher learning last? Understanding how much teachers retain their knowledge after professional development. Journal of Teacher Education, 71(5), 537-550.

Margerum-Leys, J., & Marx, R. W. (2000). Teacher Knowledge of Educational Technology: A Study of Student Teacher/Mentor Teacher Pairs.

Margerum-Leys, J., & Marx, R. W. (2002). Teacher knowledge of educational technology: A case study of student/mentor teacher pairs. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 26(4), 427-462.

Margerum-Leys, J., & Marx, R. W. (2004). The nature and sharing of teacher knowledge of technology in a student teacher/mentor teacher pair. Journal of Teacher Education, 55(5), 421-437.

Sumer, M., Douglas, T., & Sim, K. N. (2021). Academic development through a pandemic crisis: Lessons learnt from three cases incorporating technical, pedagogical and social support. Journal of University Teaching & Learning Practice, 18(5), 1.

Wenger, E. (2011). Communities of practice: A brief introduction.

Xie, J., Gulinna, A., & Rice, M. F. (2021). Instructional designers’ roles in emergency remote teaching during

COVID-19. Distance Education, 42(1), 70-87. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2020.1869526

Further Reading

Liu, S. H., Tsai, H. C., & Huang, Y. T. (2015). Collaborative professional development of mentor teachers and pre-service teachers in relation to technology integration. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 18(3), 161-172.

NSW Technology for Learning (T4L), NSW Dept of Education. Retrieved from https://t4l.schools.nsw.gov.au/

Professional Learning for Teachers and School Staff, NSW Policy, Retrieved from https://education.nsw.gov.au/policy-library/policies/pd-2004-0017

Did this chapter help you learn?

No one has voted on this resource yet.