How are LA and LxD related?

Overview

In this chapter we’ll take a look at Learning Experience Design and how it relates to learning analytics, and by extension our efforts to evaluate aspects of our work and assess students.

Why is this important?

While most of this work is theoretical at this point, there are a number of different models we can look to to use data to actually inform how we design learning experiences. It’s important to understand this relationship how educational data can inform design, and how design can inform what and how educational data is collected. This can then give us a new perspective on how we design.

Guiding Questions

As you’re reading through these materials, please consider the following questions, and take notes to ensure you understand their answers as you go.

- If you could predict the future of a lesson you planned, or learning experience you designed, what information do you think you’d want to improve it?

- What types of information would be useful to this improvement, and where could you get it?

Key Readings

Feel free to have a look at any article of interest in the SoLAR Journal of Learning Analytics Special Issue on Learning Analytics and Learning Design found here.

Gibson, A., Kitto, K.,& Willis, J. (2014). A cognitive processing framework for learning analytics. Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Learning Analytics and Knowledge (LAK ʼ14), 24–28 March 2014, Indianapolis, IN, USA (pp. 212–216). New York, NY: ACM. https://dx.doi.org/10.1145/2567574.2567610

Law, N., & Liang, L. (2020). A Multilevel Framework and Method for Learning Analytics Integrated Learning Design. Journal of Learning Analytics, 7(3), 98–117. https://doi.org/10.18608/jla.2020.73.8

- The above article is quite complex, so feel free to just skim through, or dig deep, depending on your interest – it’s ok if you don’t fully understand it. The video below is more accessible.

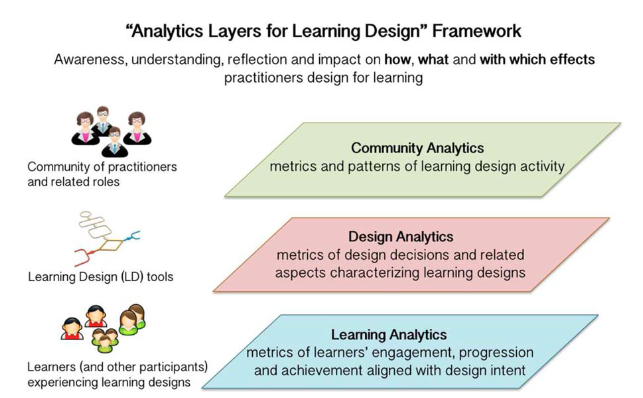

Hernández‐Leo, D., Martinez‐Maldonado, R., Pardo, A., Muñoz‐Cristóbal, J. A., & Rodríguez‐Triana, M. J. (2019). Analytics for learning design: A layered framework and tools. British Journal of Educational Technology, 50(1), 139–152. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12645

Learning Analytics informing Design

As we’ve already explored in a previous chapter, making data-driven decisions in terms of our teaching and educational administration is baked into what Learning Analytics allows us to do – if we see some learners haven’t logged in in a while, we can intervene and support their success. This is a very straightforward and linear path from collecting data to interpreting data to acting upon data, however this practice is usually based on the collection of data that is just ‘already there’, usually built into the systems we use. There is however, other ways that we can think about educational data and its collection

- Learning Analytics for Learning Design – the use of analytics during the learning design process

- Learning Design for Learning Analytics – the design of learning experiences that intentionally build in the collection of data to inform further improvements to the learning experience.

Learning Analytics for Learning Design

If you’d like to revisit definitions and nuances of learning experience design, check out What is Learning Experience Design (LxD)?

Learning Experience Design and its relationship with Learning Analytics has everything to do with planning ahead and informing learning design processes. When we design learning experiences using whatever model or framework we choose, during this process we can also think about what this process looks like and how we might improve it. Historically models and frameworks build in the ‘evaluation’ part of ADDIE without much direction on how to go about this this work. Most of the time it refers to the evaluation of the already-designed learning experience, . Given that these models weren’t developed when LA was a thing, we must extend beyond them to think about learning design on a ‘meta’ level.

Essentially Learning analytics for Learning design is the evaluation of the implementation of a model. For example, if we’re using ADDIE, it would be evaluating ADDIE as an approach, giving us data on what this process looks like, how parties involved work through it, and what comes out the other end, so that we can actually collect data about the learning design process itself including the work that goes into developing a design and the design itself. By taking a look at data related to the process, we can hopefully gain some actionable insights to inform changes and implement improvements to the process.

This concept is outlined by Hernández‐Le et al. (2019) and their model, which would involve actually looking at the interactions between learning designers and subject matter experts (SME’s), as well as how learning design decisions were made and what tools were used to make these decisions. This is quite a ‘meta’ approach, but for educational leaders, it could provide insights into the learning design process itself, when most research on the topic is currently based on interviews.

Holmes et al., (2019) looked at the Open University Learning Design Initiative(OULDI) and its seven types of LxD activities, then mapped these activities to educational data. By embedding this into LA practices, the researchers could then gain insights into how their pedagogical intentions as expressed through their LD actually manifested through student work. Once we have this data, we can then see if the intentions and the reality align, and perhaps make changes to the learning design to ensure alignment.

| Learning design activities | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Assimilative | Attending to information | Reading, watching, listening, thinking about, accessing |

| Finding and handling information | Searching for and processing information | Listing, analysing, collating, plotting, finding, discovering, using, gathering |

| Communication | Discussing module related content with at least one other person(student or tutor) | Communicating, debating, discussing, arguing, sharing, reporting, collaborating, presenting, describing |

| Productive | Actively constructing an artefact | Creating, building, making, designing, constructing, contributing, completing |

| Experiential | Applying learning in a real-world setting | Practising, applying, mimicking, experiencing, exploring, investigating |

| Interactive | Applying learning in a simulated setting | Exploring, experimenting, trialling, improving, modelling, simulating |

| Assessment | All forms of assessment (summative, formative and self-assessment) | Writing, presenting, reporting, demonstrating, critiquing |

Learning Design for Learning Analytics

While most of the above research and practice revolves around the use of analytics within the learning design process, we can also think about learning analytics and educational data from the perspective of our design work, and planning ahead for assessment and evaluation. This is where Learning Design FOR learning analytics comes in.

As we work out our learning goals / objectives / outcomes (whatever we want to call them), we can start to think about how we can effectively measure student learning, as well as the experience they have while learning, so as part of the learning design process we can brainstorm what data would be useful for the improvement of learning outcomes as well as the learning experience as a whole. For example grades are a fantastic way to measure whether an assessment if effective, but there is other information associated with grades that might tell us more, such as quiz completion times, attempt counts, time of completion etc. With a written or video task, we can look at word counts, semantic analysis etc., and these would inform both what students created and how they created it, thus informing future learning designs for the next iteration of our learning experience.

Say we’re designing a learning experience for a blended modality and as we design it we know exactly what parts of it we want to improve over time – this could be the design of learning materials, a collaborative assignment or some other aspect of the class / experience. By knowing this, we can then look at the technologies we’re using as well as any other opportunities that might give us data to inform these future improvements. In essence, we’re designing for our students to learn, but we’re also designing for learning analytics itself, so that data can feed back into our process and tell us how to improve. Some technologies may not give us the data we need, or perhaps the way we’ve designed a collaborative activity for students doesn’t give us a way to easily collect data on what they’re doing. In these example cases, we can then augment our learning design to make sure this data gets collected, but choosing a different tool or strategy.

In terms of this area of research’s links to assessment and evaluation in practice, this will really depend on the project we’re working on, so there’s no clear ‘formula’. By thinking about the initial question we wanted to answer about a learning experience we teach or have designed, we are innately engaging in evaluation work – by exploring the effectiveness of the thing we’ve created. On that ‘meta’ level, we can also evaluate the process by which we created this learning and the process by which we deliver it. For example, we can use an LD for LA approach to think about our own practice as educators. Based on our Learning Design and our pedagogical intentions for the lesson, did what we do as the teacher support our students effectively? What educational data could we use to evaluate this?

If we’re evaluating at a higher level, such as degree or program, what data can inform the effectiveness of how this program is designed – would we need more information than what is already built into the systems we use? This is really the core of what this chapter is about. In more traditional LA practices, we use learning technologies or research tools to collect data to answer questions. Sometimes we just use tools that are ubiquitous in the educational context we’re in (e.g., LMS / VLE), but if we’re being really intentional about this, we can think critically about what data these existing platforms give us, and if it doesn’t give us what we need, we can make other choices, perhaps add another technology or form of data collection, to inform what our Learning Analytics look like.

Assessment is the same, really. If we want to take a certain approach to assessment, we can design it such that we get educational data out of it that informs us whether the approach was effective in supporting teaching and learning.

Key Take-Aways

- There is an interrelationship between LA and LD in that one can inform the other, bi-directionally. Our pedagogical intentions and Learning designs can inform our LA approach and practice, and then our LA approach can inform out learning design and its implementation (the teaching and learning side).

- This applies to assessment and evaluation as well, because we can design these, and choose tools for these that will intentionally allow us to see educational data on their effectiveess.

Revisit Guiding Questions

While this is a relatively brief chapter, there’s a lot do dig into. When thinking about the projects you’ve worked on or are currently working on, try to verbally explain to yourself or a colleague how the relationship between LA and LxD works and how it might possibly inform what you do.

Conclusion / Next Steps

Being the last chapter in this book, we’ve covered a lot of ground covering a relatively new area of educational research and practice. If you’d like to learn more, feel free to explore further research, or go down the path of different types of analysis or visualisation, depending on your interests. Good luck!

References

Mangaroska, K., & Giannakos, M. (2018). Learning analytics for learning design: A systematic literature review of analytics-driven design to enhance learning. IEEE Transactions on Learning Technologies, 12(4), 516-534.

Rienties, B., Nguyen, Q., Holmes, W., & Reedy, K. (2017). A review of ten years of implementation and research in aligning learning design with learning analytics at the Open University UK.Interaction Design and Architecture(s) Journal – IxD&A,33, 134–154. Retrieved from http://ixdea.uniroma2.it/inevent/events/idea2010/index.php?s=102

Rienties, B., & Toetenel, L. (2016). The impact of learning design on student behaviour, satisfaction and performance: A cross-institutional comparison across 151 modules.Computers in Human Behavior,60, 333–341. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2016.02.074

Did this chapter help you learn?

100% of 4 voters found this helpful.

Provide Feedback on this Chapter