What makes an effective OLC?

Overview

In the last chapter we read about what a Learning Community is, it’s links to educational and learning theory, as well as how it can differ across contexts and modalities. In this chapter we’ll be examining how a learning community can be effective in supporting learning in an online space.

Learning Outcomes

After working through this chapter, you’ll be able to:

- Understand how cognitive and affective expression of self helps to form a learning community / community of practice

- Examine how formality and hierarchy / power may play a role in OLC’s.

- Examine communities in terms of technologies / spaces and their affordances

Why is this important?

Communities and Learning Communities can naturally pop up anywhere, whether they are intentionally established or not. To gain a better understanding of how learning communities in an online space can actually enhance and support learning is important to understand, so that we can recognise the difference between a learning community that simply exists, and one that ensure the learning is happening and that the learning community enhances the experience.

Guiding Questions

As you’re reading through these materials, please consider the following questions, and take notes to ensure you understand their answers as you go.

- How did learning communities you’ve been involved with in the past help you learn?

- What aspects of a learning experience are most important?

- What technologies lend best to learning communities in the 2020s?

- What do you as a learner expect of an online learning community?

Key Readings

LaPointe, L. and Reisetter, M. (2008). Belonging online: Students’ perceptions of the value and efficacy of an online learning community. International Journal on E-learning 7(4), 641-665.

Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (2000). Critical inquiry in a text-based environment: Computer conferencing in higher education model. The Internet and Higher Education, 2(2-3), 87-105. (Optional, if you’re already familiar with this paper.)

What does Effective mean for an OLC?

When looking at research on learning communities, what becomes clear quite quickly are that the what effective means for online learning communities can have a few different answers. Focusing on specific type of benefit as a singular focus, or trying to cover more than one will result in different considerations for the design of a community. Broken down, there are a few different ways to look at what makes an OLC effective.

- Increased retention and completion: This benefit is all about making sure students don’t leave. In many studies researchers have found that learning communities provide a connection to the people and places of an institution, and this leads to students staying in the community, as well as staying enrolled due to this connection. A Google Scholar search provides many studies that demonstrate this, with some studies emphasising that these benefits especially benefit those in minority demographics.

- Increased Learning Gains: This benefit is all about how learning communities support learning itself. There are many studies exploring how task-oriented discourse can support learners’ understanding of a topic as well as completion of certain tasks and assignments, leading to higher marks / grades and higher academic success. Again a Google Scholar search gives us ample evidence to demonstrate that communities can help to increase student success, often coupled with increased retention and completion.

- Increased Satisfaction: Additionally, research often explores student perception of their learning experiences, with a focus on satisfaction, which itself is often linked to their sense of accomplishment, academic success and other factors. When learners are satisfied with their engagement in a learning community, they often perceive that they’ve learned more, or that the class they’re taking is of a higher quality.

Identity & Sense of Belonging

When people get together, whether it be face-to-face or in an online setting, there are obviously different social dynamics at play. Hughes (2007) outlines in their paper the reality that different identities play in how online learning communities form, function and persist, and how equity and inclusion play a role. Whenever we engage online, there are some who participate in the open, some who sit back and listen, some who try to dominate, some who defer to other and everyone in between. This is simply due to the diversity that exists in any learning environment or context – we are all diverse learners with different backgrounds, senses of self, and identities and how our identities are constructed can inform how we participate and feel about our place in an online learning community.

In her Identity Congruence model, Hughes asserts, based on work by Wenger (1998) on Communities of Practice (CoP) that we all have multiple identities we use to interact with others, and by reconciling these identities we can shift and adapt to our role in a community fluidly. For example, how we interact with our superiors at work is different than how we interact with our teachers or friends. Additionally, the ways we interact online can differ based on platform (e.g., Twitter, LinkedIn, Facebook, etc.) and modality (e.g. text, video, voice). Based on these multiple means of ‘being’ in an online community, our inclusion and exclusion in specific interactions or entire communities may differ:

- we may choose to sit back and listen in a Zoom meeting, or we may choose to speak up and dominate the conversation

- In text-based discourse we may be more willing to voice our opinions when compared to in an on-campus meeting

- When taking part in a lesson that we are not confident in, we may not be willing to ask questions, and may prefer to do so over private text channels like email

For all of these examples, the question becomes: Who are we in different online communities, and how does this affect our learning?

It should be noted that this concept of identity construction can be self-constructed (intentionally) and/or be imposed on us by cultural factors, socialisation, inherent cultural inequities and others. As educators it’s important for us to understand this, and to consider how these factors may play out when we are setting up and facilitating online learning communities.

In LaPointe and Reisetter’s study (2008), the researchers found that many online students valued interactions with their instructors including hearing or reading personal experiences, and being able to ask questions of them. When it came to peer interactions, this value was varied, with some agreeing that this interaction was beneficial, while others did not find it so, with some students noting the ‘mechanical’ nature of the discussions and the feeling of needing to write carefully.

For students new to the online environment, from non-traditional backgrounds, or first year students, promoting a sense of belonging within an online class can lead to a more robust OLC, a higher sense of social and emotional wellbeing and by extension, increased engagement, higher learning satisfaction and learning performance (Thomas, Herbert, and Teras 2014; Xiaojing et al. 2007).

Additionally, in their review of Professional Learning communities Stoll, et al.(2006), the authors point out five key traits of a learning community:

- Shared values and vision

- Collective Responsibility

- Reflective Professional Inquiry

- Collaboration

- Promotion of group and individual learning

Note that if you teach in schools / K-12, these traits may not be directly applicable, so it’s important to consider who our learners are (as always) and what we want them to get out of any learning community, whether online or face-to-face.

The Role of Presence

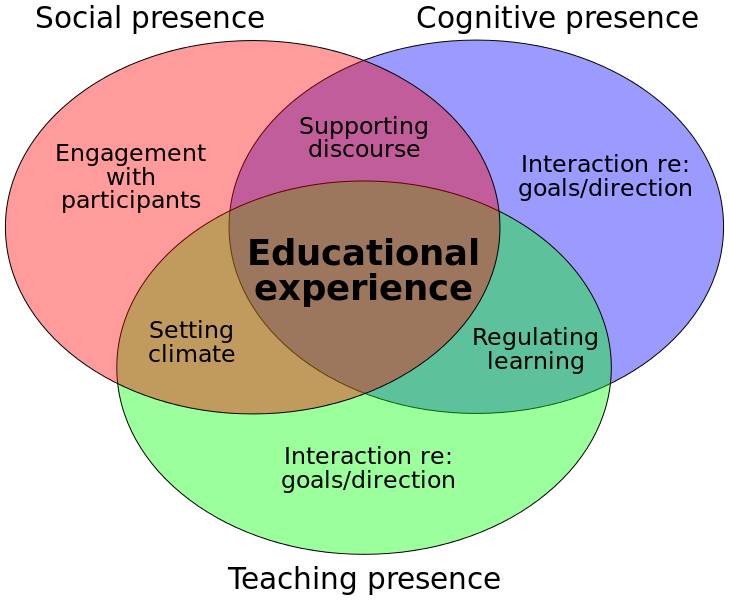

Another important consideration for learning communities in online spaces is the idea of presence. Garrison, Anderson and Archer (2000) put forth the Community of Inquiry model, which shows different levels of presents that exist in any online environment. This is also linked with how we construct our identity online – while there is no right or wrong way to do it, seeing your instructors face, hearing their voice, and interpreting their body language in an online environment definitely has a different effect on our sense of identity and place in a community when compared to having only text and static imagery as a means of interacting with our teachers. If we extend this to our fellow learners, the same can be true, which lends to an important question. Does how we present ourselves online affect how we learn, and how effectively we can learn?

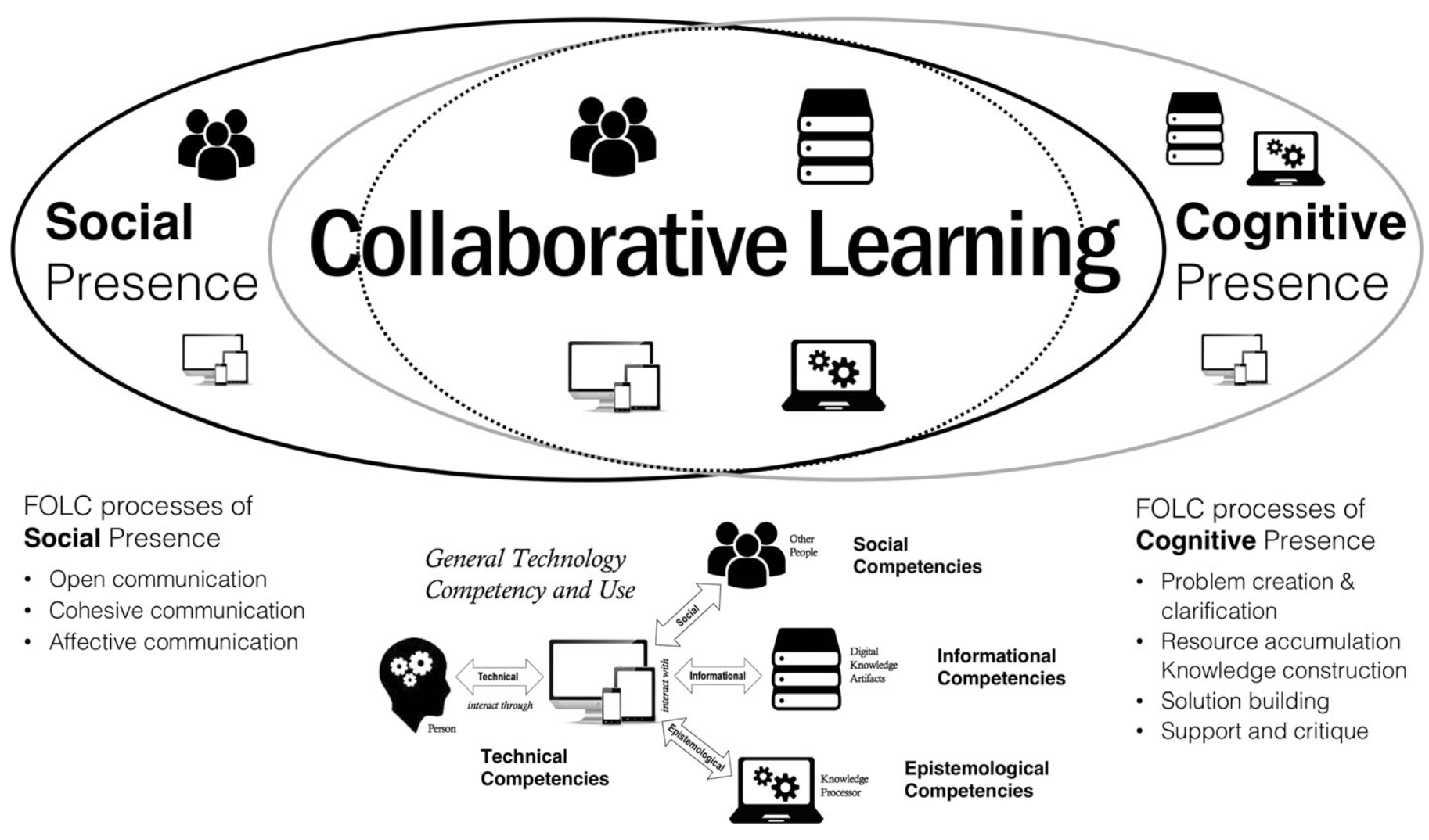

Blayone, et al. (2017) extend this idea further in their model, through a discussion of ‘democratising learning’, meaning that learning occurs within the community and requires participation and contribution from members of the community to be fruitful. This may be in opposition to more traditional methods of teaching and learning that place the instructor at the centre with individual students learning in an isolated fashion, which may seem familiar to many of us. By breaking free of this individual view of learning, we may be able to blend the social and cognitive aspects of learning, with minimal support from a teacher, leading to a practical application of the ‘sage on the stage vs. guide on the side’ model of teaching and learning that King (1993) spoke about many years ago.

Student Perceptions

While it might be easy to simply have a prescribed list of ‘what works and what doesn’t’ for ensuring the effectiveness of online learning communities, the reality is much more nuanced. Take Ke’s study (2005), for example in which they analysed student perceptions of an online community. Findings were grouped in many different themes that covered many aspects of human group dynamics.

- Students posted intentionally and only when it was meaningful for their learning or the conversation, and thought carefully before posting what they did.

- Most interactions in the online environment were academic in nature, with little social interaction

- For group work, timing was important to get going on a project and to ensure it was done on time.

- Students favoured participation that was monitored by the instructor

- Students noted they needed to adapt to a new way of interacting with their peers and instructors, having come from a more traditional classroom environment

- Student mentioned a reluctance to rely on others for their learning, meaning they wanted to hold the agency of their learning to themselves.

- Students had a feeling of unfairness based on differing levels of participation amongst the larger group

- When working together, the term ‘responsibility’ was used often, with this being important in the completion of group work

- Students were overall satisfied with their experience.

While this finding was for one class over 17 years ago, it does tell us a lot about how students experience and online learning community. As many of us have experienced and been a part of an online learning community (now more so due to the COVID-19 pandemic) many of these responses may ring true, while others we may not agree with or may never have considered. This stems back to student diversity and how all learners come to a learning experience with previous experiences in the classroom and online – experiences that we may no nothing about, but should be mindful of anyway.

Technologies and Means of Communication

Over the years, many different types of technologies have allowed communication in educational settings. The table below provides a brief summary of what types of information we can share with these technologies. Based on this, we can then consider how these different forms of communication can convey what we want, and how this contributes to the formation of a learning community.

| Type of Technology | Text | Pictures | Audio | Video | Embodied |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ✅ | ✅ | ||||

| Bullitin Board Systems (BBS) | ✅ | ✅ | |||

| Discussion Forums | ✅ | ✅ | |||

| Web 2.0 Technologies (Blogs, Wikis, etc.) | ✅ | ✅ | |||

| Text Chat | ✅ | ||||

| Channel-based Chat (e.g., Slack, Discord, Teams) | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | |

| Online Collaborative Documents | ✅ | ||||

| Video Chat | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ||

| Virtual / Game-based environments | ✅ | ✅ | |||

| AR, VR, MR (together called XR) | ✅ | ✅ |

Much of the research in how learning communities can benefit students focuses more on the aspects of community itself and the pedagogical principles behind such communities, and not so much on the details on the specific technologies used. From this we can assume that the technology may not play a big a role as we think it does, however it’s definitely worth considering how different technologies and how we use them to interact with one another can support a learning community and its goals in the online environment.

To consider this, we should go back to foundational theories in the use of technology, such as Mayer’s Cognitive Theory of Multimedia Learning, as well as the principles associated with it. While most of these principles focus on how we as humans interact with technology, more recent research has focused on the use of more collaborative technologies and means of interacting with learning materials.

Cognitive Affordances

From a cognitive perspective, social technologies make learning through a Social Constructivist (Vygostksy, 1967) much easier as we are exposed to different cultural and individual interpretations of the same pieces of information through interaction with others. Additionally, pedagogical approaches used in OLC’s such as shared note taking, collective annotation of learning materials and simply sharing student creations within a class accomplish the same – community-based learning through structured activities directly linked to learning objectives or assessment tasks.

Additionally, Kirschner et al. (2009) present a review of research comparing individual learning and group learning from a cognitive and learning science perspective. They suggest that while tasks with a low level of complexity can be easily completed by an individual, as tasks (learning, problem solving) get more complex, having multiple ‘brains’ on hand to tackle the issue is more cognitively efficient because you literally have more brain processing power available. When learning in this setting, the requirements to process, coordinate and recombine novel information to make it meaningful for all members of the group is distributed across multiple brains, making this distribution more efficient in face-to-face as well as online environments.

Affective Affordances

Biens (2016) presents a discussion of how social presence and the affective (emotional) aspects of online learning communities and discourse relate to intrinsic power dynamics in society, and the considerations this presents. For example, with a more intimate learning community where students are encouraged to share their thoughts and opinions about controversial topics, group dynamics may play out in similar ways to external society, bringing in social hierarchies, prejudices and others aspects of inequity into the learning community itself.

Again, one can consider this technology agnostic – applying both to face-to-face learning as well as online learning, but it’s important to consider in technology-based environment how we can share emotions with each other. Tone of voice, emotional state, comedic intention and other nuances of communication are easy to interpret when you can see another’s face and read their body language, however it can be more challenging in a text-based online environment. More contemporary means of text-based communication allow for emoting, through the use of emojis 😉 and reaction GIFs, though these means of communication are sometimes not ubiquitous in many learning environments, sometimes leading to misunderstandings, differing interpretations of intention and perhaps even conflict. In short, it’s amazing what multimedia technologies can do to convey meaning, and express emotion, especially when learners are physically and geographically distant from each other more and more.

This plays even more into pedagogical approaches to technology enabled learning that emphasise community, humanity and care.

For more on the affordances of different technologies, check out What makes technology good for learning?

Key Take-Aways

- There are multiple ways of considering how a learning community can be effective for learning

- Presence and sense of belonging are key aspects of the success of learning communities

- The same ‘academic’ cultural issues present in face-to-face environments may exist online (we bring our cultures and expectations with us)

- Technology has the ability to support all the core principles of effective learning communities by allowing key interactions to happen on a cognitive and affective level.

Revisit Guiding Questions

Now that you have an introduction to what makes and effective online learning community, consider how your experience as student in learning communities (online or otherwise) contributed to your learning. Did the designer-instructor follow principles and models you’ve learned about? Did they do something completely different that worked or didn’t? How do you think this affected the learning community as well as your and your peers’ ability to learn?

References

Beins, A. (2016). Small talk and chit chat: Using informal communication to build a learning community online. Transformations, 26(2), 157-175

Blayone, T. J., Barber, W., DiGiuseppe, M., & Childs, E. (2017). Democratizing digital learning: theorizing the fully online learning community model. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 14(1), 1-16.

Dagley, M., Georgiopoulos, M., Reece, A., & Young, C. (2016). Increasing retention and graduation rates through a STEM learning community. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice, 18(2), 167-182.

Hughes, G. (2007). Diversity, identity and belonging in e-learning communities: Some theories and paradoxes. Teaching in higher education, 12(5-6), 709-720.

Ke, F. (2005, October). Forming Virtual Learning Community within Online Course: Students’ Perspectives. In Association for Educational Communications and Technology Annual Meeting.

King, A. (1993). From sage on the stage to guide on the side. College teaching, 41(1), 30-35.

Kirschner, F., Paas, F., & Kirschner, P. A. (2009). A cognitive-load approach to collaborative learning: United brains for complex tasks. Educational Psychology Review, 21, 31-42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-008-9095-2

Stoll, L., Bolam, R., McMahon, A., Wallace, M., & Thomas, S. (2006). Professional learning communities: A review of the literature. Journal of educational change, 7(4), 221-258.

Thomas,L., Herbert, J., and Teras, M. 2014. A Sense of Belonging to Enhance Participation, Success and Retention in Online Programs. The International Journal of the First Year in Higher Education 5 (2):69–80. doi: 10.5204/intjfyhe.v5i2.233.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1967). Play and its role in the mental development of the child. Soviet psychology, 5(3), 6-18.

Wenger, E. (1998) Communities of practice: learning, meaning and identity (New York, Cambridge

University Press).

Further Reading

Bulu,S. T., & Yildirim, Z. (2008). Communication behaviours and trust in collaborative online teams. Educational Technology and Society, 11(1), 132-147.

Dolan, J., Kain, K., Reilly, J., & Bansal, G. (2017). How Do You Build Community and Foster Engagement in Online Courses?. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 2017(151), 45-60.

Gan, Y., & Zhu, Z. (2007). A learning framework for knowledge building and collective wisdom advancement in virtual learning communities. Educational Technology and Society, 10(1), 206-226.

Hartnell-Young, E. (2006). Teachers’ roles and professional learning in communities of practice supported by technologies in schools. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education, 14(3), 461-480.

Jenkins, H. (2009). Confronting the challenges of participatory culture: Media education for the 21st century (p. 145). The MIT Press. Retrieved on 29 March, 2022 from https://library.oapen.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.12657/26083/1004003.pdf

Liu, X., Magjuka, R. J., Bonk, C.J., & Lee, S.-H. (2009). Does sense of community matter? In Orellana, A., Hudgins, T. L., & M. R., Simonson (Eds.) The perfect online course: Best practices for designing and teaching (pp. 521-543). Charlotte, NC: Information Age publishing.

Pozzi, F., & Persico, D. (Eds.). (2010). Techniques for Fostering Collaboration in Online Learning Communities: Theoretical and Practical Perspectives: Theoretical and Practical Perspectives.

McInnerney, J. M., & Roberts, T. S. (2004). Online learning: Social interaction and the creation of a sense of community. Educational Technology and Society, 7(3), 73-81.

Did this chapter help you learn?

No one has voted on this resource yet.

Provide Feedback on this Chapter