What are online learning communities?

Overview

In this chapter, we’ll dig into what a learning community is, how it’s defined and online learning communities may differ across modalities. then we’ll look at how these communities can benefit learning along with some pros and cons.

Learning Outcomes

After working through this chapter, you’ll be able to:

- Understand what a learning community is and how they differ across modalities and sectors

- Understand the role that communities play in benefitting learning

- Critique different online communities (examine pros and cons)

Why is this important?

Before we jump into developing an online community (including choosing its purpose, culture and technology) its important that we gain and understanding of both the history of online learning communities and how they can support or inhibit learning.

Guiding Questions

As you’re reading through these materials, please consider the following questions, and take notes to ensure you understand their answers as you go.

- What learning communities have you been involved with previously? Are you part of one now?

- How do you think a learning community can support learning? Through what theoretical lens?

- What’s the most productive approach to community and collaboration online in your opinion?

Key Readings

Reconceptualising Community in Palloff, R. M., & Pratt, K. (2007). Building online learning communities: Effective strategies for the virtual classroom (pp 25-43). John Wiley & Sons.

Conrad, D. (2014). Interaction and communication in online learning communities: toward an engaged and flexible future. In O. Zawacki-Richter & T. Anderson (Eds.) Online distance education: Towards a research agenda (pp 281-402). Retrieved from http://www.aupress.ca/books/120233/ebook/14_Zawacki-Richter_Anderson_2014-Online_Distance_Education.pdf

Learning Community Defined

How would you define community? What about a learning community? This is no doubt different for different people, depending on where and how they study. There are many different definitions of learning community (see Key & Hoadley, 2009), so however you’re approaching the topic, whether it be as a military instructor, corporate trainer, learning designer or school teacher, you may have a different definition, depending on your context and what you want a learning community accomplish.

If we first think about traditional modalities (where and how we learn) such as a face-to-face, on-campus, classroom mode of learning, there is decades of research and theorising on the topic of what a community means. Rovai (2000) discusses the meaning of a classroom community as:

a feeling that members have of belonging, a feeling that members matter to one another and to the group, that they have duties and obligations to each other and to the school, and that they possess a shared faith that members’ educational needs will be met through their commitment to shared goals.

Rovai, 2000

The author outlines that this community is based on the context (education), the purpose (learning) and the timing (how long the community exists, such as a course, a unit or learning or semester). Other communities may have different factors that define, so stating these obvious traits of a learning community can help us to place it in the larger world of community itself. When we look at the definition above, whether a community uses technology or not, this defintion still stands.

In terms of learning in professional settings, Stoll et al. (2006) provide this defintion:

…a group of people sharing and critically interrogating their practice in an ongoing, reflective, collaborative, inclusive, learning-oriented, growth-promoting way (Mitchell & Sackney, 2000; Toole & Louis, 2002); operating as a collective enterprise (King & Newmann, 2001).

Stoll, et al. (2006)

Given that we all learn in different sectors, from schools, polytechnic, university and professional settings, the defintion of a learning community can vary, so its important to explore our own contexts to gain an understanding of what ‘community’ might mean.

To disrupt what you may currently think about learning communities and their potentially formal and structured nature, check out the talk by Educational Technology researcher Sugata Mitra, and consider how learning communities can be on a spectrum between intentionally design and facilitated to completely spontaneous, and what this may mean for your practice.

For more on this experiment, check out Hole in the Wall on Wikipedia.

Kids can Teach themselves (via TED)

Alignment with Learning Theory

When we revisit learning theories, there are a couple of that align really well with the concept of learning communities, especially that of online learning communities. For a review of learning theories, check out How do we Learn with Technology?

Constructivism at its core is about how knowledge, meaning and our interpretation of information is individual constructed based on the learner’s own mindset, and experience / prior knowledge. This is different than Social Constructivism, which asserts a similar concept – that meaning and knowledge are constructed through the lens of society, culture, and by extension social interaction with others within our culture. Through the lens of Social Constructivism, learning communities can support learning because they provide a discreet setting from which learners can derive meaning and gain knowledge. In other words, if we learn in isolation (e.g., reading a book without discussing it, watching an instructional video without discussing it) the meaning we derive from this new information may be misinterpreted, misunderstood or lack connection with prior learning. Through discourse with others, and through discussion of our own interpretations of new information, we can gain consensus, understand other perspectives – perhaps even other valid interpretations of the same information – as well as check out understanding against others.

Adding to our previous definitions, learning communities therefore are “models of thinking about instruction based on the dual platform of technology and constructivist theory” (Johannsen, Peck, Wilson, 1999, p.1).

When it comes to online learning communities, we can look to Seimen’s Connectivism (2005), as this framework can help us to think about what learning looks like in a connected world. Without social and collaborative technologies, online learning communities simply wouldn’t be possible. Additionally, given that knowledge is no longer in the hands of a select privileged few, but for the most part freely online, how we interact and consume new information is definitely in a connected manner.

Lastly, online learning communities more often than not involve some sort of sharing, creation or curation of information, which aligns with Papert’s Constructionism theory (Papert & Harel, 1991). This theory, predicated on the concept of ‘learning by making’, ties direction into the co-creative nature that online learning communities take, from shared discourse and resource creation, to collecting materials and summarising them, creation is often at the heart of online learning communities.

Transactional Distance

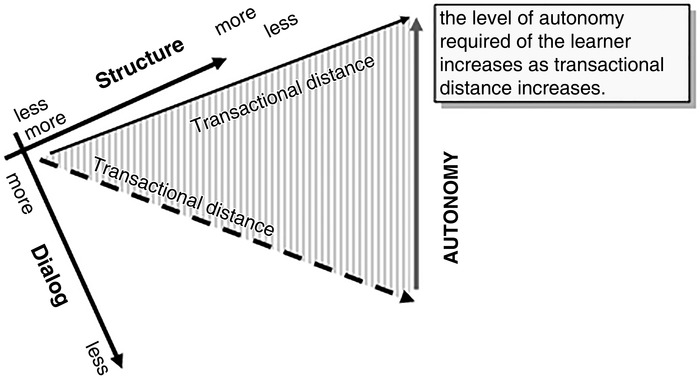

Another foundational theory comes from Moore (1989;2003) – the same Moore that gave us the 3 types of interactions in distance learning – in the form of Transactional Distance Theory. This theory was established as a framework to help researchers explore distance learning experiences in the 1970s and 1980s and quickly became an important way to think about how we connect online as well.

In a nutshell, Moore’s idea is that the psychological distance between instructor and learner is dependent on interrelated factors including how structured the learning experience is and how much dialogue this structure affords as well as how personalised the learning experience is (i.e. how autonomous the learner is). In other words, if the learning experience is highly structured, usually the instructor and learners will be communicating more, whereas if the learning experience is less structured, that ‘distance’ increases, resulting in less dialogue.

This theoretical approach to distance and online learning allows us to think about how much we talk to each other, and how this can be intentionally set up in the learning experiences we design and facilitate.

So why learning communities?

In the previous sections we’ve learned about how learning communities can support learning through alignment with learning theory, sense of community and shared construction of knowledge. In short, the combination of these aspects of learning communities mean that learners are more successful in thier learning outcomes when they are in a group, learning together.

As a pedagogical approach

One thing that is true is that learning communities can exist in many places at many different times and serve single or multiple purposes. In the video below, instructors at a university in the Netherlands talk about Team-based learning, Problem-based learning and how these two pedagogical approaches rely on learning communities to enhance the learning of individual students.

When we consider the differences between how we interact in the classroom, and how we interact online, we should be mindful of these differences and how they’ll affect learning communities across modalities.

As a result of Modality

To review modality in online learning, along with associated terms, check out the section on Learning Modalities in How do we Learn with Technology?

Much of how Learning communities are established is predicated on where learning usually happens. For example, when working together in a physical classroom, it’s quite easy and natural to get instant feedback. We can read body language, tone of voice and get a pretty clear understanding of each other as we interact. When working in a synchronous (same time) online environment such as through video chat, we can also get this sort of feedback, however the slightest delay in the video feed or change in video quality can affect our ability to understand each other. Additionally, the lack of a full-body view of our peers can sometimes influence how we interpret their words and actions, and its much more challenging to participate in more embodied learning activities (e.g., find a group by moving to X corner of the room; act out a scenario). In asynchronous situations however, the time to respond and even the beginning of discourse can take place at different times. One member of the community may not chime in for weeks after the first, and while some may respond immediately, others may take a while due to external responsibilities. This is inherent in the flexible nature of online learning, and in subsequent chapters we’ll look at how we can mediate these issues to ensure a community thrives around them.

Scale, Scope and Purpose

Before we look at the details of what makes an online community effective for learning, we should first think about the purpose an online community can serve in any learning experience, and this includes the scale and scope of the community. Things to consider:

- Scale

- Scope

- Length of Time

- Purpose

- Motivation to participate

Beyond our standard question of ‘Who are our students’ as part of analysis of student needs (see ADDIE learning design model for more), an important question is simply ‘How many students are there?’. If we’re teaching a small class of less than 20 students, this would look very different than a MOOC (Massive Open Online Course) that has 3000, and even different still to a small discussion class of 3 or 4. Depending on the size of the learning community we want to establish, the decisions we make around design and facilitation may be different. For example, a larger class will often mean there is more engagement (obviously) and sometimes less need to prompt learners to do so. For smaller groups however, engagement may depend on the willingness of learners to actually chime in and say something, which is up to each learner, regardless of incentives or rewards that may be present.

When it comes to the length of time a learning community exists for, Akyol et al. (2011) found an interesting difference in short (6 week) vs long (13 week) units of learning as shown in the figure below as analysed through discussion forum data. As you can see, learners who engaged in a short learning experience quickly formed groups, most likely because they were learning in a compressed format and may have needed more support and more communication. On the other hand, those in a long term experience shared more affective information with each other, most likely due to a longer time period to get to know their peers – as opposed to needing to be ‘all business’. While this is just one study, it suggests that time is an important consideration because the focus of learner interactions when they have varying degrees of time with one another may have a different focus.

Let’s have a look at a few examples of what learning communities can look like with the following considerations in place:

Discreet Learning Experience Supports

The most obvious purpose is to support a group assignment, as is many of our collective experience working together in an educational setting, whether it be in class or online. In these sorts of communities, the entire purpose is to work together on a project within a limited time frame – perhaps a few weeks or an entire semester or term. In this community the entire purpose is the creation of an artefact that determines a grade / mark for each individual student.

Scope: Small: An individual class or project

Length of Time: Usually quite short – a week to a month or two

Purpose: Academic: To support successful completion of a group assignment, and to gain experience working in a group (online or face-to-face)

Motivation: Extrinsic – the mark/grade.

Learning Cohort Supports

If traversing through a course or degree with the same fellow students over time is how you study, some learning communities are set up to allow interactions between students and with instructors. These can serve as mechanisms to share valuable information about formal studies, events and a Q&A area for discussion of topics unrelated to assignments or specific classes.

Scope: Program / Course Degree – the actual size depends on how many students are going through the course / degree at the same time.

Purpose: Academic & Non-academic: o support the experience of everyone enrolled in a specific course / degree

Length of Time: The length of the course / degree – 6months to a few years.

Motivation: Extrinsic – academic support leading to academic success; Intrinsic – community and affective support mechanisms through interactions with peers.

Communities of Practice

These learning communities have been researched for years – while sometimes structure or unstructured, Communities of Practice (CoP’s) are learning communities that gather professionals seeking to improve how they work, usually centred around a specific interest they may have (see Wenger, 2011). For example, a CoP might be set up in a region for exploring AR technologies in Schools, while another might be using Curriculum mapping in universities. Sometimes CoP’s are set up as part of a project with funding associated, and sometimes they are merely to group like-minded individuals to learn or share ideas.

Scope: It varies – could be a small group of people within a department all the way up to thousands of people across nations.

Length of Time: Usually a longer time period, from a few weeks to a few years.

Purpose: Professional Learning and reflective practice

Motivation: Intrinsic – community and support mechanisms through interactions with peers to improve practice.

Common Technologies to support OLCs

Learning Communities in online settings can take many forms, and exist in many different contexts – sometimes we have them set up at work for us as part of a community of practice, but online, other times these can be organised by others or as part of an organisation or formal group.

Examples of online learning communities can be found in many places, with the below examples a good place to start:

Institutionally-supported Spaces

- Online classes

- Discussion Forums

- Chats

- Webinars

Non-institutionally supported Spaces

- Facebook Groups

- LinkedIn Groups

- Twitter Hashtags (e.g., search for #learningdesign and you’ll find a great community)

- Blogs and associated comments

- ‘Thought Leaders’ posts (e.g., if a practitioner is active of social media, they might have a following and communities can pop up as a result)

- MOOCs (Massive Open Online Courses)

- Discord and Slack teams – you may find that some communities listed online have dedicated chat areas for their work (these can usually be found through other social networking means)

We’ll get into these in more detail in later chapters, but it’s good to have an idea of the breadth of what’s possible when considering using learning communities in an online space. As more and more of us learn and work online these days, understanding the diversity in learning communities is the first step in understanding their value and how they can word to support learning.

Pros and Cons

When we consider all the different ways we interact online in the 21st century, there are always different ways we can interpret these experiences, wither productive for learning or not. The way a technology is designed can affect our learning, the nature of our cohort and of ourselves can affect our learning, and more importantly how the learning community is designed by the instructor is also a part of this.

Thinking about the pros and cons of different learning communities we engage in can be very subjective, as it relates back to the goals of the learning community itself. Questions we can ask as we start to explore Online Learning Communities (OLCs) can include:

- Who is this community for?

- When do they want to engage?

- How long should this community persist for?

- How confident are the members with technology?

- What technology would be the best fit for them?

Key Take-Aways

- ‘Learning Community’ has many different definitions

- Most older research links a learning community Constructivism and Social Constructivism, but other theories such as Connectivism and Constructionism and provide a useful lens to think about LCs

- Transactional Distance tells us that how an OLC is set up can affect how psychologically separated we are from one another.

- There are a wide range of purposes and scopes for online learning communities

Revisit Guiding Questions

Now that you’ve read a little bit about learning communities and the history of OLCs, as you reflect on your own experiences in OLCs, what theoretical ties jumped out to you? What purpose did these communities serve, and were they set up to foster learning in the best way possible?

References

Akyol, Z., Vaughan, N., & Garrison, D. R. (2011). The impact of course duration on the development of a community of inquiry. Interactive Learning Environments, 19(3), 231-246.

Garrison, D. R., & Arbaugh, J. B. (2007). Researching the community of inquiry framework: Review, issues, and future directions. The Internet and Higher Education, 10(3), 157-172.

Jonassen, David, Kyle Peck, and Brent Wilson. 1999. Learning with Technology: A Constructivist Perspective. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

King, M.B. & Newmann, F.M. (2001). Building school capacity through professional development: Conceptual and empirical considerations. International Journal of Educational Management 15(2), 86–93.

Mitchell, C. & Sackney, L. (2000). Profound improvement: Building capacity for a

learning community. Lisse, The Netherlands: Swets & Zeitlinger.

Moore, M. G. (1989). Three modes of interaction. A presentation of the NUCEA forum: Issues in instructional interactivity. NUCEA Conference, Salt Lake. American Journal of Distance Education, 3(2), 1–7.

Moore, M. G. (2013). The theory of transactional distance. In Handbook of distance education (pp. 84-103). Routledge.

Papert, S., & Harel, I. (1991). Situating constructionism. Constructionism, 36(2), 1-11.

Rovai, A. (2001). Building and sustaining community in learning networks. Internet and Higher Education, 3, 285-297.

Siemens, G. (2005). Connectivism: A learning theory for the digital age. International Journal of Instructional Technology and Distance Learning, 2(1). Retrieved from http://www.itdl.org/

Stoll, L., Bolam, R., McMahon, A., Wallace, M., & Thomas, S. (2006). Professional learning communities: A review of the literature. Journal of educational change, 7(4), 221-258.

Toole, J.C. & Louis, K.S. (2002). The role of professional learning communities in international education. In K. Leithwood & P. Hallinger (eds), Second international handbook of educational leadership and administration. Dordrecht:Kluwer

Xiaojing, Liu, Richard J. Magjuka, Curtis J. Bonk, and Lee Seung-hee. 2007. “Does Sense of Community Matter?: An Examination of Participants’ Perceptions of Building Learning Communities in Online Courses.” Quarterly Review of Distance Education 8 (1):9-24.

Wenger, E. (2011). Communities of practice: A brief introduction.

Did this chapter help you learn?

100% of 1 voters found this helpful.

Provide Feedback on this Chapter