How do we design and facilitate an OLC?

Overview

Now that we’ve explored how learning communities in online settings can effectively support learning, in this chapter we’ll look at how we can design and facilitate OLCs to encourage learning and promote discourse and mutual support amongst learners.

Learning Outcomes

After working through this chapter, you’ll be able to:

- Understand how OLC’s relate to models of learning design

- Consider effective facilitation techniques for online learning communities

- Understand sustainability in online communities and how this can be achieved.

Why is this important?

While it may be enough to read research and books all about how great OLCs may be, it’s another thing entirely to actually design, set up and run one. Having a good understanding of concrete strategies that we can use to foster interaction, model discourse (regardless of formality) and create a sense of community can help us as designers and instructors to enhance learning in ways unrelated to outcomes and assessment.

Guiding Questions

As you’re reading through these materials, please consider the following questions, and take notes to ensure you understand their answers as you go.

- In your previous experience, was it clear what purpose a learning community served?

- How have you established a learning community in the past? How have your instructors?

- What do you think is needed to persist a community? Should it be encouraged or forced?

- Is it better to have extrinsic or intrinsic motivation for engagement in an OLC?

Key Readings

Brook, C., & Oliver, R. (2003). Online learning communities: Investigating a design framework. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 19(2).

DiRamio, D., & Wolverton, M. (2006). Integrating learning communities and distance education: Possibility or pipedream?. Innovative Higher Education, 31(2), 99-113

Yuan, J., & Kim, C. (2014). Guidelines for facilitating the development of learning communities in online courses. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 30(3), 220-232.

Learning Communities and Learning Design

As we’ve learned in previous chapters, a theme of integrating learning communities into the pedagogical design (or learning design) of a class is an important step in making sure communities actually enhance learning. As Kear (2010) notes “that when e-learning courses are designed with some care and attention to the meaning of learning in groups and communities, students’ experiences can be very positive.” (p.2).

If we revisit models of learning design such as Backwards Design, ADDIE, 4CID model and others (see What is Learning Experience Design (LxD)? for a review), almost all of these models do not mention learning communities at all, instead we must as teachers and learning designers infer that learning communities are embedded in the catch-all category of ‘learning activities’.

For this reason, educators have license to consider the role that interpersonal relationships as well as how communication and collaboration can actually contribute to the attainment of learning objectives. While it may seem rigid and highly structured to focus on competencies and a structured hierarchy of activities to ensure that students learn what they need to learn, the increased attention on inclusive practices, as well as care-based pedagogy / pedagogies of care mean that we don’t need to have cold, disconnected learning experiences anymore.

Designing Learning Communities

While we may not have concrete guidance from established models of learning design, there is much we can learn from previous inquiry into online learning communities. For example, Charalambos et al. (2004) has a good list of what a good online learning community takes to thrive. In their exploration of a learning community for teachers, they outline important aspects of planning and application of an OLC (paraphrased below).

- What is your overall goal for the Learning community?

- Who is the community for and what experience do they have with technology and learning onlin?

- What do they need to learn?

- Do all potential participants have access?

- What will they be doing as part of the learning community?

- How long will it last?

- How do you know the community is valuable to its members?

Additionally they recommend that:

- Facilitators give ownership to participants

- Ensure that participants are committed to the work they’re doing

- The appropriate technologies / tools are selected to facilitate the community’s aims

- Appropriate training is provided to ensure success.

Based on these recommendations, and other insights we’ve gained over previous chapters, it’s safe to say that online learning communities really need to have intention behind their design and setup.

Rovai (2000) also outlines 8 factors that influence a sense of community in online environments, which are outlined in detail in the article. While this article is 22 years old as of the writing of this chapter, all of these areas are still being researched and form important considerations when designing and facilitating online communities.

Some factors above are simply built in to communities based on the technology we choose, some are based on our intention and direct action as instructors, while some are simply self-perpetuating. Paloff et al. (2001) also outline 7 steps to running an online learning community as follows:

- clearly defining the purpose of the community;

- creating a distinctive gathering place for the group;

- promoting effective leadership from within;

- defining norms and a clear code of conduct;

- allowing for a range of member roles;

- allowing for and facilitating of subgroups; and

- allowing members to resolve their own disputes.

In the same article, the authors recommend that instructors be actively engaged by:

- engaging students with subject matter;

- accounting for attendance and participation;

- working with students who do not participate;

- understanding the signs of when a student is in trouble; and

- building online communities that accommodate personal interaction.

In their book, Paloff and Pratt (2010) also outline stages that teams go through as part of their development, including:

- Normative Stage (getting to know each other)

- Unity / Problem Solving Stage (group comes together to get to work)

- Conflict Stage (when group works through conflict or disagreement to reach consensus)

- Action Phase (when groups are working together productively)

- Termination Phase (the wrap up of the group activity)

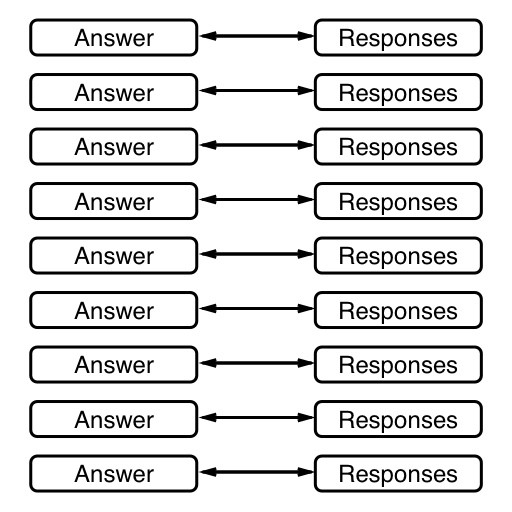

Additionally, Yoon and Johnson (2008) conducted an analysis of 33 students engaged in online team work, and categorised how they engaged with each other into a different taxonomy, as outlined below.

From all these different ways of thinking about and conceptualising what happens in an online environment when engaging with others, there are trends – there is a start, a middle and an end to this experience, regardless of what we choose to call it. For the rest of this chapter, similar concepts are used, but using different terms.

Induction

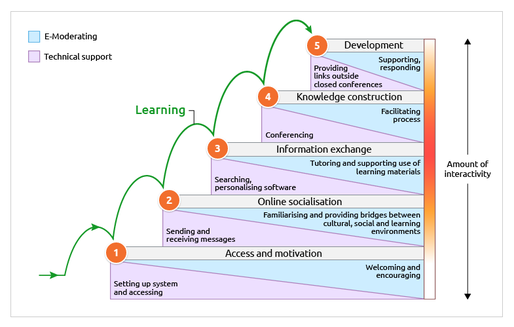

Gilly Salmon, a researcher who’s been exploring online moderation of student activities for over 20 years, developed her 5-Stage Model to articulate the stages at which instructors can on board and facilitate learning in an online space.

- Access and Motivation: This is an important first step – student need access to the learning community (which may be in an LMS – Learning Management System) or elsewhere. Students also need to be welcomed into that space appropriately, which is where Teaching Presence can play a role.

- Online Socialisation: In this step learners get used to the online environment and start to make connections. This can be in the form of near-ubiquitous introductions and getting to know you activities or other ice-breakers.

- Information Exchange: This is where learning starts to happen, with students gaining more experience in the technologies they’re using to communicate, while also beginning to look at learning materials

- Knowledge Construction: Related to Social Constructivism, this is the step where people interact to share meaning and interpretation of new information, with the instructor facilitating this process through prompts and engagement.

- Development: This extends from knowledge construction to encourage engagement with external materials and communities, while allowing for sharing and support within the online environment.

As Dolan at al. (2017) note, the distance between individuals within a learning community is never based on geographical separation, but pedagogical separation, meaning its how we design, establish and facilitate a community that brings people closer together to make the community more viable and valuable.

How do we present ourselves?

This author chooses to show his face as soon as possible within any online community – this simply borne out of a desire to establish an informal and human-centred learning environment where he is not seen as a formal authority figure, but a peer who has similar ideas, thoughts, challenges and love of puppies. Consider the difference between presenting yourself in the online environment with a professional headshot, and very formal attire compared to standing in a park walking with friends. The psychology distance, power dynamics, social hierarchy and ‘approachability’ of an individual can differ considerably based on how we choose to present ourselves.

As Dolan et al (2017) summarise, the use of first names, modelling of appropriate and expected behaviour, letting go and allowing students to lead and have their own conversations and transparency around what student should expect are all important parts of establishing Teaching presence as it relates to communities.

Additionally, with the rise of pedagogical approaches such as Pedagogy of Care / Care-based Pedagogy and practices related to ensuring inequity through the respect for personal identity in online spaces, we should also be mindful that some members of the community may not want to present themselves in the same ways as others (e.g., webcam on or off or even the profile image they choose), so allowing flexibility in how learners present themselves is very important.

Participation

In a study exploring student perceptions of the differences between learning communities in a face to face and online environment, Murdoch and Williams (2011) found that learners did not report significant differences in how they experienced the learning community between modalities. They did however report that their perception of the instructor’s responsibility in facilitating the OLC in the online environment was higher, with the researchers asserting that it was also the instructor’s intention behind the design of assignments and tasks that tied into to the learning community that influenced this result. In other words, the learning community on its own may have differed more if the instructor hadn’t linked the design of instruction (e.g., learning materials, tasks, etc.) with what happened in the community.

Ferguson, et al. (2013) analysed both formal and informal online discussions with teenagers and suggested that “the teaching role can be seen as socialising learners into particular ways of talking about topics, in order to work towards greater intersubjectivity” (p.16) highlighting the fact that teachers, when facilitating online learning communities should model and orient students to the environment and to the topic of discussion (see the first 3 stages of Salmon’s model above).

It’s all in the setup

DiRamio and Wolverton (2006) developed eight principles based on prior research and asked educational leaders, teachers and researchers to rank them in order of importance (see table below) . While this does not provide empirical evidence of what actually works, it provides insights into experts’ perceptions of what is important when working with students in online learning environments.

| Learning Community Principles | Mean score |

|---|---|

| 7. Encourage students to share their own experiences and ideas in online discussions and/or postings | 3.56 |

| 4. Encourage students to take responsibility for their own learning | 3.55 |

| 5. Use instructor-guided peer questioning to encourage student-to-student interaction | 3.49 |

| 6. Incorporate reflective writing exercises, including student self-evaluation | 3.42 |

| 8. Instructor shares own internal processes (ways of thinking) with students | 3.33 |

| 2. Use group projects to promote collaborative learning | 3.30 |

| 1. Cluster two online classes around an interdisciplinary theme | 3.02 |

| 3. Integrate an extracurricular, student affairs component into the online class (i.e. social activity) | 2.71 |

To facilitate or not to facilitate?

One question that may come up is simply of whether or not a facilitator-teacher is even required – after all, for years students have organised themselves into study groups, used social media to help each other and work together, so why would a facilitator be necessary? This comes down to purpose and planning of the learning environment. While spontaneous study groups can serve a general support purpose for learners, they may relegate themselves back to the notion that learning happens individually, and that learning together is not something that they’re expected to do.

This again relates to teaching presence in that “…without instructor’s explicit guidance and ‘teaching presence,’ students were found to engage primarily in ‘serial monologues’” (Pawan, Paulus, Yalcin, & Chang, 2003, p.143). In other words, students will share experiences or opinions but won’t make connections between readings or materials to create new knowledge within the community. It is sometimes common to see online discourse break down into simple summaries of learning materials with a ‘yes I agree’ or ‘thank you for sharing’ response.

And this comes down to facilitation and how learners are prompted to respond to a problem or question. Consider the following two discussion forum prompts, just as an example:

Prompt: Who was the first president of the United States. Discuss with your peers, and reflect on your learning.

Prompt: Why is George Washington so revered in American culture? How does his status as a slave owner conflict with the Bill of Rights statement ‘all men are created equal’ and how can this conflict be reconciled?

How we facilitate online learning communities, including the tone we set, the questions we ask, and the expectations we set can have a profound effect on how much learning and community building actually happens. Considerations for how questions and prompts are structured were born out of this author’s time as a learning designer, supporting the design of online learning experiences for many years. While not rooted in specific research, these were useful questions to ask for instructors:

- Should Ambiguity be built in? Should there be a correct answer to the prompt, or many interpretations and potential solutions? In a class where the majority of ‘stuff to learn’ is about memorisation and knowledge, this is where problem-based activities come in. Contextualize that knowledge, provide a real-world scenario in which students cannot solve alone.

- Should you leave engagement optional? Often, a prompt or a question might have many answers, or only one answer, and the best way to facilitate learning in this situation is to pose a question that requires students to talk to each other to find those answers.

- Should we require participation as part of a mark or grade? Often discussion posts in online spaces are based on a reward for participation. Given that most incentive to complete tasks in formal educational settings are based on rewards – points for completing tasks – its important to think about how informal or formal learning communities factor into this idea of ‘required participation’.

- Should we allow for more organic conversation? Of course, but there should be a balance, no? There is no easy answer to this, but given the formal nature of discussion prompts and an instructors responsibility to ensure students are learning, leaving learning communities to be completely spontaneous and organic may lead to learners discussing elements unrelated to the topic at hand or may lead to continued misunderstandings of key concepts. For this reason, and based on the research mentioned in this chapter and others, social interaction as well as formal discussions of new concepts and ideas may be the most effective strategy.

- Should prompts be islands of themselves or linked to tasks? When activities are presented in isolation and don’t built to anything, this is not representative of a true learning experience outside of the classroom. When we finish school there is always a requirement to keep learning new skills, but in the workplace, for example, we learn new facts, which integrate into skills, which integrate into projects and creative endeavours. Sometimes learning experiences lead to a dead end, but most times they do build upon each other.

These considerations also relate back to the fundamental aspects of teaching and learning as well as the concept of the ’empty vessel’ – are students simply empty vessels to be filled with knowledge, or do they bring their own experiences, expertise and knowledge to learning? The answer is obvious, but how this relates to learning communities can remain a bit muddy. Bjork and Bjork’s (2011) concept of Desirable Difficulties may also present ideas when thinking about how to set up and facilitate communities of learners. This concept refers to the challenges to learning, including missing information needed to complete a task, being challenges to the point of frustration and other experiences we all have while learning that are actually beneficial to it. This again leads back to the benefits of learning communities in that multiple viewpoints, with multiple lenses and compounded experience can help to overcome these difficulties and support learning in many ways.

Conclusion/ Termination and Sustainability

So we have an established learning community and its flourishing. Great! What happens next? How does it conclude, wrap up or continue. Depending on the duration we want for our learning community, it could last a day, a week, a month, a year or longer, or it may never end, so based on our intention as the convener and facilitator we may eventually have to say goodbye. While there’s not much research on effective strategies for concluding a learning community, there should be a conclusive end in place, instead of just having it go silent out of nowhere. A common approach in this case is to have a concluding activity, where students can reflect on what they learned, share information if they wish to keep in touch, or to have a more social event to do the same, either face-to-face or online.

Such an experience provides a book end for learners, so they understand their time with each other is coming to an end. In different contexts with different learners, this may vary in how it is implemented, but it can be useful also in ‘teasing’ other learning events that maybe coming later, whether it be other classes, follow-up professional learning workshops or something else.

While not very common in many educational settings, sustainability of the community is also an option. It’s quite normal that when we complete a class or learning experience that that’s the end of it – the learning experience is a discreet experience that only lasts for the duration described. Another option is to provide learners with a more sustained learning community space, one that perhaps lives outside of an institutionally supported technology space, like on a Social Networking or Professional Networking site (e.g., Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, etc.). While we’ll examine this in a later chapter in more detail, allowing learners to stay in touch, and providing them with a means to do so without leaving that to happen organically (organised by the students alone), this can give the community longer life, and a more sustained experience for the learners.

Considerations

When developing and facilitating online learning communities there are many factors to consider that can play a role in the success of the learning community and its effectiveness for learning.

Technology & Training

First, there is the technology – when we choose a technology for any teaching and learning aim, we have to think about its affordances and its features, ranging from how learners will even access the technology, to what it allows us to do. As we discussed in previous chapters there are cognitive and affective affordances (among others) that can allow learners to communicate and collaborate, depending on the technology chosen.

Once it has been chosen it’s a matter of training learners and modelling its use for them to ensure they are using the technology effectively. This may include short guides or tutorials on how to use the technology generally, then showing specific tips on using more advanced features.

Learners and their time

When learning online, modality plays a very important role. If we’re learning synchronously or asynchronously, whether we’re using a computer or a mobile device, flexibility in how learners engage can also be a factor. Some students may work nights, may have family responsibilities or work commitments, or even live in a different time zone. For these reasons, learners in asynchronous learning communities will often contribute at different times, and this can have an effect on decision-making and progress within the group.

This same idea can have everything to do with motivation, and motivations range from anywhere from a simple love of learning and lack of regard for marks or formal qualifications, to the requirement to complete with high marks / grades to advance one’s career. While these differing motivations within a single group may have an impact on the development and sustainment of a learning community, whereas if all members of the community have the same motivation (e.g., workplace health and safety training vs. study groups to pass a high stakes exam) the community may be designed and facilitated very differently.

Key Take-Aways

- There are many different, yet similar ways of thinking about the progression of a learning community

- Through these phases, there are a number of strategies we can use as facilitators and designers to ensure the community is successful.

- There are a few important things to consider such as technology choice and flexibility that may impact the learning community’s success.

Revisit Guiding Questions

With all the research that’s been done on learning communities in online spaces over the years, in reflecting on our guiding questions, do you think there is a sure fire way to build a community that works for everyone? This is perhaps a rhetorical question, but it raises the important point that a community takes more than the person who designs it – it is, after all, a community that depends on engagement of others

Conclusion / Next Steps

Designing and Facilitating an Online Learning Community involves many choices and many steps to ensure it works to support learning effectively. In the next chapter we’ll examine the use of Social Networking Sites (SNS’s) in education, and how they are perceived and how we should think about them in our practice.

References

Ally, M. (2008). Foundations of educational theory for online learning. Theory and practice of online learning, 2, 15-44. 18

Bjork, E. L., & Bjork, R. A. (2011). Making things hard on yourself, but in a good way: Creating desirable difficulties to enhance learning. Psychology and the real world: Essays illustrating fundamental contributions to society, 2(59-68)

Charalambos, V., Michalinos, Z., & Chamberlain, R. (2004). The design of online learning communities: Critical issues. Educational Media International, 41(2), 135-143

Chickering, A. W., & Ehrmann, S., C. (1996). Implementing the seven principles: Technology as lever. American Association for Higher Education Bulletin, 49(2), 3-6.

Dawson, S. (2008). A study of the relationship between student social networks and sense of community. Educational Technology & Society, 11(3), 224-238.

Dolan, J., Kain, K., Reilly, J., & Bansal, G. (2017). How Do You Build Community and Foster Engagement in Online Courses?. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 2017(151), 45-60.

Ferguson, R., Gillen, J., Peachey, A., & Twining, P. (2013). The strength of cohesive ties: Discursive construction of an online learning community. In Understanding learning in virtual worlds (pp. 83-100). Springer, London.

Kear, K. (2010). Social presence in online learning communities. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Networked Learning 2010, 3-4 May 2010, Aalborg, Denmark. Retrieved from http://oro.open.ac.uk/21777/

Murdock, J. L., & Williams, A. M. (2011). Creating an online learning community: Is it possible?. Innovative Higher Education, 36(5), 305-315.

Palloff, R. M., & Pratt, K. (2010). Collaborating online: Learning together in community (Vol. 32). John Wiley & Sons.

Palloff, R. M., Pratt, K., & Stockley, D. (2001). Building learning communities in cyberspace: Effective strategies for the online classroom. The Canadian Journal of Higher Education, 31(3), 175.

Pawan, F., T. M. Paulus, S. Yalcin, and C. Chang. 2003. Online learning: Patterns of engagement and interaction among in-service teachers. Language Learning and Technology 7 (3): 119–140

Rovai, A. P. (2000). Building and sustaining community in asynchronous learning networks. The Internet and higher education, 3(4), 285-297.

Salmon, G. (2013). E-tivities: The key to active online learning. Routledge.

Salmon, G. (2003). E-moderating: The key to teaching and learning online. Psychology Press.

Yoon, S. W., & Johnson, S. D. (2008). Phases and patterns of group development in virtual learning teams. Educational Technology Research and Development, 56(5), 595-618.

Further Reading

Creating Online Learning Communities (Times Higher Education)

Did this chapter help you learn?

100% of 1 voters found this helpful.

Provide Feedback on this Chapter