How do we ensure effectiveness?

Overview

In this chapter we’re going to explore various methods for ensuring the quality of the technology-enhanced and online learning experiences we might design or create. There are already a number of ways we can benchmark quality, and exploring additional ways to collect information and continually improve our lessons and learning experiences is an important step. Note that this chapter does not cover general quality assurance related to course or degree development, but focuses mainly on the quality on the technology side of things.

Why is this important?

Designing learning experiences that use technology (as most do these days) involves a certain level of experimentation, but also one that must include some sort of instructional rigour and quality assurance. While we have models of learning design, models of tech integration and steps to go through for designing these experiences, it’s good to have an idea of what a quality learning experience actually means in terms of design and learning experience, along with some common ways to get more information so we can improve what we’ve created.

Guiding Questions

As you’re reading through these materials, please consider the following questions, and take notes to ensure you understand their answers as you go.

- How can we evaluate the quality and effectiveness of technology enabled and online learning experiences?

- Should all learning experiences be consistent for learners, or should they all be different?

- In your previous work working with technology in an educational setting, did you use any benchmarks for quality, or did your teachers ever show you any?

Key Readings

Donnelli-Sallee, E. (2018). Supporting online teaching effectiveness at scale: Achieving efficiency and effectiveness through peer review. Journal of Educators Online, 15(3), n3.

Jaggars, S. S., & Xu, D. (2016). How do online course design features influence student performance?. Computers & Education, 95, 270-284.

McGahan, S. J., Jackson, C. M., & Premer, K. (2015). Online course quality assurance: Development of a quality checklist. InSight: A Journal of Scholarly Teaching, 10, 126-140.

The Why and the Who

While there are already many standards and quality frameworks that exist in educational settings, the evaluation and quality of learning experiences that involve technology, while related, include some unique additions related to the technology itself. As we know what works and what doesn’t work in terms of web design, information presentation, navigation and other areas (borrowed from web design standards) and we have evidence for how people learn effectively using technology (borrowed from learning science and distance education research), we have ways to benchmark what a learning experience should include, and generally what it should look like. Without such benchmarks, whatever we design may present challenges for learners, inhibit learning and make things difficult to find. That’s the why.

The who is an interesting question as well. Obviously we are wanting to make sure the learning experiences we design and create are good for the learners, but in what sense? As the financial landscape of education has continually changed over the last decade, education in many parts of the world has now become a purchasable commodity, and with the rise of online review sites and the wide expression of opinions, student satisfaction is now a benchmark of educational quality, something that was not the case 20 or 30 years ago. Interestingly, student perception of online class quality actually differs from what established frameworks for online class quality profess (Ralston-Berg et al., 2015), and many times this relates to the requirement for engagement with instructors and fellow students, even thought educators know this is an incredibly effective way to learn, if implemented well. This presents an interesting philosophical question: Are we creating learning experiences so that the students are satisfied with the learning experience, or so that they learn? While obviously that question, presented in a binary manner doesn’t represent the nuances of this issue, it’s an interesting question, and one that may have a different answer in different contexts. If I’m designing a MOOC (Massive Open Online Course) as a marketing and recruiting tool for my school, obviously satisfaction is a big part of it, but if I’m training nurses, the effectiveness of learning will be the focus. When figuring out how to evaluate and ensure the quality of our experiences, this is something we must consider.

Standardised or a Free-for-All?

When designing and developing technology-enabled or online learning experiences, one thing to consider is how learners will respond to it. We’ve learned a lot about how people interact with web based technologies since the 1990s so on the design and navigation side of things, this is a pretty easy thing to deal with. Standardised means of presenting web links, titles, menus and other common conventions for the presentation of digital information is commonplace. We’ve even had standardised means of creating online learning experiences for almost 30 years, in the form of SCORM, though its use has diminished in recent years.

When considering how digital learning experiences are presented, the question has always been about customisability vs a good student experience. In early LMSs (e.g., WebCT, Moodle), everything was so highly customisable that every class looked different, perhaps even down to the navigation menu items and colors the instructors could choose. Most students, when asked about their experiences, found it confusing and difficult to find materials and assignments without a consistent design in place, leading in part to concept of Learning Interface Design. As a result, more modern learning platforms (e.g, Canvas, D2L, Blackboard Learn) adopted a more uniform design, with the ability to customise on a limited scale. This balance of control vs. consistency has been at the core of the conversation around the design of online learning experiences for years. Interestingly, after the COVID-19 pandemic forced many students to learn online, this consistency in design actually led to another problem – all the classes looked so similar and the instructors didn’t customise enough that many students became lost, not actually knowing which class they were in.

The lesson here is that when we design a learning experience, we must also be mindful of the student experience – one that might include multiple online or technology-enabled classes at the same time, and differentiating between them is an important thing to do.

When it comes to the pedagogical side of things, this is another story. Should this be standardised? Do we want students to have a similar learning experience, regardless of the subject matter they’re learning? Do we want them to follow the same path and do same types of assignments again and again? This is one element of quality assurance for learning experiences that is an ongoing discussion in the community, and there is no correct answer.

Artefact or Person First?

Along with the debate about standardisation, another common spectrum of practice is around how quality is measured and ensured. In some organisations emphasis is placed on evaluating and ensuring the quality of the artefact – the online class itself as it lives inside a learning platform – while on the other end of the spectrum, is the investment in professional learning opportunities and resources for the teachers who are teaching online (e.g., workshops, peer review. etc.). Of course, many educational institutions choose to use both approaches at the same time, but some opt to forego one for the other. This decision really depends on how learning experiences are created, because the choice of approach will really depend on that. If the teacher is merely acting as a SME (Subject Matter Expert) and Instructional / Learning Designers and Educational Developers are doing most of the work, then an artefact-first approach might be most appropriate. If, however there is not enough staff to support all the classes being created and taught, more emphasis can be placed on resources to support the staff in their own work.

The difference between these approaches can be interpreted differently as well. If an artefact is being evaluated to a set of standards, this may seem much more heavy handed and evoke thoughts of a dystopian ‘big brother’ peeking into teachers’ freedom to teach how they want. On the other hand, if professional development resources are provided with no benchmarking, the culture of the organisation may default to one of blind trust that students are getting a good experience.

If you want to learn more, feel free to search your workplace or learning context for resources on how they ensure quality. Units and departments that include ‘Instructional Support’, ‘Learning Design’, ‘Educational Excellence’ and other similar phrases exist in many organisations now.

Checklist or Development Tool?

It might sound crazy but this is very common, especially in the online learning / eLearning space. As many teachers teaching fully online may not have taken a fully online class before, and may never have been taught how to teach effectively, rubrics provide a way to benchmark what a quality learning experience looks like in these modalities.

One such rubric is called Quality Matters. This 42 point rubric is very extensive and very popular in many parts of the world. The rubric itself is not an open resource, but organisations must pay to adopt and use it, as well as pay to have staff be ‘certified’ to implement the rubric and provide feedback using it. For this reason, there are many educators who are not fans of this framework, and opt to use others or to create their own.

It seems as though almost every organisation has their own way of doing this, so a simple google search will provide many different examples of how these rubrics or checklists can be presented. Most include basic elements that ensure students get the information they need (e.g., Is there a class calendar? is there an instructor bio? Are due dates accurate?), while others may go into more detail covering things like accessibility, UDL and even assessment design.

What’s interesting is that these checklists can actually serve multiple purposes – they can either serve as a checklist after something has been created, or they can serve as a tool for checking quality as something is being developed, and sometimes, even both – it’s used during development, then as a way to ‘cross the T’s and dot the I’s’ when the development is completely.

Mini Case Study

From 2013-2019, this author developed several versions of a course quality rubric / checklist for use in different educational settings in collaboration with colleagues. The first version in 2013 was initially met with resistance from academic staff, who saw it as a performance evaluation tool, even suggesting having their union have a look at it if it continued to exist in its current form. With revisions, a final version served primarily as a feedback mechanism for teachers who were working with a learning designer to develop online classes over a period of 6 months (the normal timeline for such a project at the time). After the COVID-19 pandemic forced all educators in the same context to develop and teach online within a week or two, the ability to provide feedback was shifted from the unit supporting this effort, to the instructors themselves, necessitating a change in format from a feedback form to a simple self-check form. This, combined with the use of templates within the learning platform, helped to make life easier for the many instructors who had never taught online before, let alone seen what a good online class looks like.

Peer Review

Depending on the culture of an educational institution, sometimes the learning / instructional designers will provide feedback using checklists and rubrics, and other times other instructors will. This may form part of the peer review process, but with a focus on the design and development of online learning experiences. This is particularly useful when peer reviewers work in the same subject area, as they’ll be familiar with specific methods on how to teach in that area, whereas learning designers may not. Working with fellow instructors also makes the process feel less robotic and include a human element, while also leveraging a checklist as a development tool. To address the issue of subject-area expertise, peer reviews can also be conducted using Teaching Squares in a 2×2 pattern, whereby 2 people review one class, with one reviewer knowing the subject matter, and the other not.

Review of Teaching

Peer reviews of teaching are quite common in many contexts, from schools / K-12, to universities, polytechnic and military education. The general idea is this: when teaching, we have other teachers observe us in the classroom and provide feedback on how we can improve our practice. This is usually part of our professional development / learning practice and has to happen at least once a year or so. This also happens online, but not as often in online settings.

Educational Data

When we want to look at the actual effectiveness of teaching as measured by learning outcomes, then grades / marks are a place to look for obvious reasons as they give us a benchmark on how successful students were at meeting learning objectives / outcomes. While some may consider marks and grades to be arbitrary, especially in contexts where grades are arbitrarily curved, they are still a good indicator of the learning experience’s quality from an outcomes-based perspective.

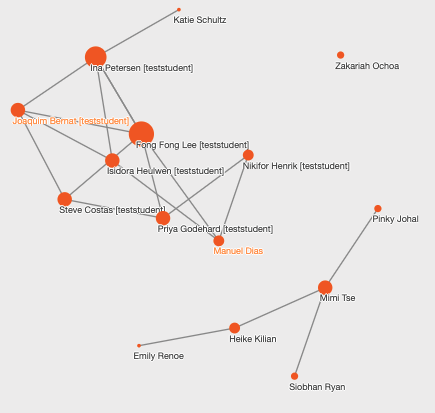

Another place to look is learning analytics, to look at how the design and the pedagogical intentions of the instructor / designer actually manifested in reality. For example, if the idea was that students would collaborate and learn from each other in discussion forums, but there wasn’t much interaction happening, this can inform pedagogical action and design changes to try to encourage more of this in the future. For more on learning analytics see Emerging Trends in Learning Technologies and Introduction to Learning Analytics.

Feedback from Learners

When developing a new learning experience for students, it is important that subjective feedback is gathered based on their experience. Without this feedback, any changes the course would be solely based on instructor perception of student experience, which may be biased or contain gaps in knowledge.

By including this feedback mechanism, any future changes to the learning experience will have learner-centred evidence to inform future revisions, thus closing the loop (E in ADDIE). This can be done in both formative and summative fashion, with changes made on the fly during the learning experience as well as after it has ended, respectively. If we know something is needing an update and we wait until the end of the class or lesson, whatever changes we could make to benefit students who are currently studying would be lost. Below are a couple of sample surveys with questions included.

Week 2 or 3 Survey

Early in the class, it is important to gather formative feedback from learners in case anything about the course design is not optimal. This survey is all about gathering initial feedback from students on how easy it is to find content and materials, how information is communicated to them and how easy the course is to navigate.

Sample introductory wording:

This week 3 evaluation is in place to get some initial feedback on the class so far. Please feel free to provide any feedback you think would be valuable to yourself and other students.

All responses are anonymous.

Suggested questions:

- Are you having trouble finding or accessing any materials within this class? If so, please give some feedback on how it could be set up differently.

- What are the best features of the class so far?

- Are you clear on what is expected of your as a student in this class, or are you a bit confused about what you’re supposed to be working on?

- Any other Comments?

End of class Survey

This survey is a more summative mechanism for gathering feedback at the students entire experience navigating the class, completing activities and assignments, their workload the their perceived value of all of the above.

Sample introductory wording:

This survey is intended to gather your reflections on your experience in this newly redesigned class for future improvements.

Your responses are anonymous.

Suggested questions:

- What were the best features of this class?

- How do you think this class could be improved?

- The class provided effective opportunities for active student participation in learning activities [Likert]

- I was provided with clear information about the assessment requirements for this class [Likert]

- The assessment methods and tasks in this course were appropriate given the class aims [Likert]

- The class workload and expectations were appropriate [Likert]

- How many hours per week do you think you spent on class work?

- The assigned readings and resources added value to my learning experience [Likert]

- I have learned a great deal in this class [Likert]

- Overall, I was satisfied with the quality of this class [Likert]

- How do you think this class could be improved?

Research in General

While there is a difference between evaluation and research, it’s important to note that most evaluation techniques have their roots in basic research design, including the steps involved and the focus on questions that need to be answered and how to effectively answer those questions.

For a quick review of research methods, check out the video below.

Beyond Completion

One thing to think about is that after a project is completed – a lesson planned and implement, a class created and taught – that we should not consider our work done. In many settings, the first offering of a new or updated class is considered to be pilot test, so evaluation is incredibly important to ensure that kinks are ironed out and the class or learning experience is in a good place to live for a while on it’s own. That being said, as part of ongoing reflective practice for educators of all kinds, we should never assume that our work is done – the more we learn about our own practice, the more we can improve our students’ experiences.

Key Take-Aways

- There are multiple ways to evaluate and ensure quality for both technology-enabled and online learning experiences.

- Benchmarks such as checklists written by teaching staff and learning designers can serve as a development or evaluation tool

- Other data such as learning analytics and grades / marks can provide insights into required changes and student perceptions of the experience.

Revisit Guiding Questions

Now that you’ve read a bit about different approaches to evaluate a learning experience, think about how you would evaluate your own designs in your context. What would work and what wouldn’t? How willing would your colleagues and students be to participate in these efforts and how would you go about implementing them?

Conclusion / Next Steps

In the next chapter we’ll think further into the future, beyond the evaluation of an individual learning experience. Considering how the COVID-19 pandemic has changed how people learn, it’s important to think about how the field of instructional and learning design will change in the coming years and what that will mean for our work.

References

Ralston-Berg, P., Buckenmeyer, J., Barczyk, C., & Hixon, E. (2015). Students’ Perceptions of Online Course Quality: How Do They Measure Up to the Research?. Internet Learning Journal, 4(1).

Did this chapter help you learn?

100% of 2 voters found this helpful.

Provide Feedback on this Chapter